Tensions ran high as a stern detective interrogated a group of American students at a Beijing police station. The questions were fired in Mandarin, but the students stood their ground and responded in kind. This was not a scene from a blockbuster thriller or an episode of Locked Up Abroad, but the final exam for the Mandarin and Chinese Culture class Lee Sheldon designed at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Using Mandarin-speaking actors and an elaborate backstory involving a stolen manuscript, Sheldon worked with the course’s instructor to deliver the class as a narrative-driven game that immersed students in Chinese culture without ever having to leave the Troy, New York campus.

Sheldon is no stranger to the art of crafting narratives, and his unique classes mark the convergence of his multifaceted career as a screenwriter, author, producer, game designer and academic. While working as a writer in Hollywood, he penned over 200 episodes for TV classics like Charlie’s Angels, Cagney and Lacey and Star Trek: The Next Generation. He transitioned into game design in the mid-1990s and then to academia when he accepted an offer to teach screenwriting and game design at Indiana University Bloomington.

“After a couple of years teaching and becoming increasingly bored—I feared my students were as well—I tried to think of a way to make the classes more interesting to all concerned,” said Sheldon. His “Aha” moment came when he thought to re-conceive his game design class as an Alternate Reality Game (ARG), a complex live-action game format he had experimented with during his days as a game designer.

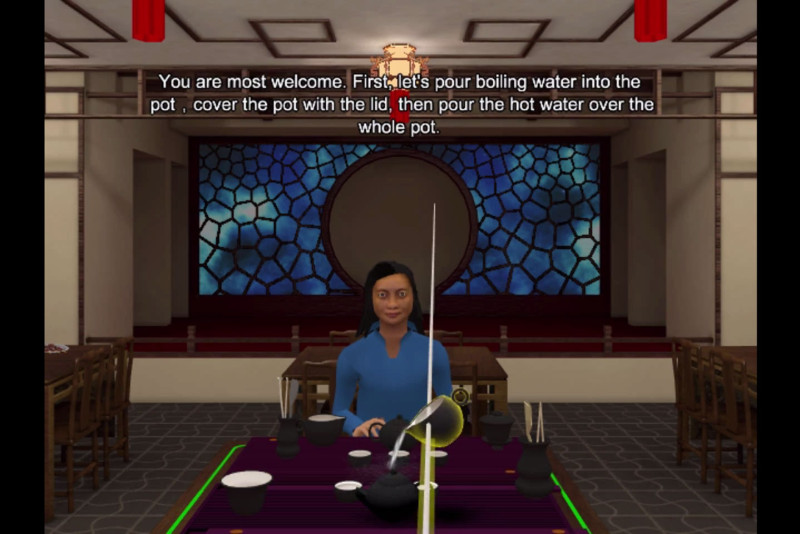

A look at an "interrogation" and how students speak Chinese with actors in this alternate reality game: