In his report, “Teacher Leadership and Deeper Learning for All Students,” Berry profiles a public high school in Los Angeles serving a high-needs population. With very few resources, but a dedicated staff of teacher-leaders, Social Justice Humanitas Academy (SJHA), shows that deep, rigorous learning can take place in all communities and with all kinds of learners. The report quotes a student who noted a palpable difference between SJHA and middle school:

“At first when I came here I was a little thrown off by the amount of respect I received. . . . I wasn’t just treated as a student, I was treated as a person. In middle school it was always like, ‘You’re the student, I’m the teacher. I have more power over you.’ And here it’s not like that. And I feel like that’s what makes students grow. It’s transformational. . . . you grow to respect other people.”

Teachers at SJHA serve as advisers to the same group of high school students throughout their four years at the school. They also mentor several more students who have been identified as needing extra support. Classes are not taught in silos, but rather teachers collaborate on interdisciplinary approaches so students can see connections between things they learn. The high school offers fewer courses, but they are more aligned with one another, and staff have time to effectively collaborate. And learning at SJHA is personalized, not with adaptive software, but by checking in with students every five weeks, looking at a variety of data sources, and determining what supports each student will need to continue growing as a learner.

If all of these commitments sound like a lot, they are. Teachers at SJHA work very hard to meet their students’ needs and are stretched thin, much like teachers in more traditional contexts. The difference is that those same teachers worked to develop the strategy to support students and are committed to its continued success. They chose their principal, who also teaches a few classes a week. They aren’t using textbooks they hate or following curriculum because someone else told them to; they made those decisions together. And by having that agency and ability to be flexible and change the plan to meet different learners, teachers are also showing students what it means to lead.

The school has also achieved some amazing results by traditional measures. Their graduation rate is 94 percent and students go on to attend some of California’s top universities. Discipline issues are nearly nonexistent, with a .2 percent suspension rate last year. And, perhaps most importantly, 93 percent of students say they feel safe at school, despite gang violence in the surrounding area.

HOW DO WE DEVELOP TEACHER-LEADERS?

There is a lot of great research on what works in educational practice. However, the U.S. school systems overall haven't been good at implementing those best practices because, in many cases, they try to layer on top of existing and failed systems. Authentic collaboration is rarely found in U.S. schools -- according to Berry, 50 percent of teachers say they’ve never even seen another colleague teach.

Consequently, some of the best available examples of how to improve teacher quality and promote teacher leadership lie in models offered by other high-performing places, like Finland and Singapore. While quite different from one another, they both give teachers much more time to collaborate and have systemized practices for teachers to observe, discuss and improve one another’s teaching through activities like Lesson Study.

“Teachers, like every other human being, are products of their past,” Berry said. No matter how good professional learning is, it’s got to be really good when it comes to helping teachers make transformational changes to their practice, because before that they were students in a system that taught them very differently.”

Overcoming a tendency to fall back on what’s familiar in the classroom is particularly hard when there are so few U.S. examples of teacher-led deep, rich learning. Berry cites research showing that even in some of the most successful schools using these strategies, a deficit of inspirational models makes the work feel daunting.

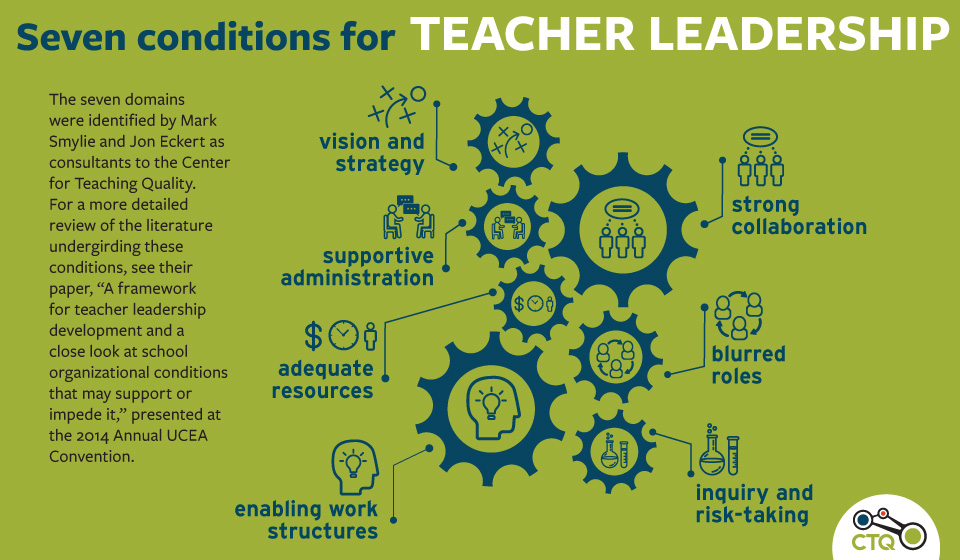

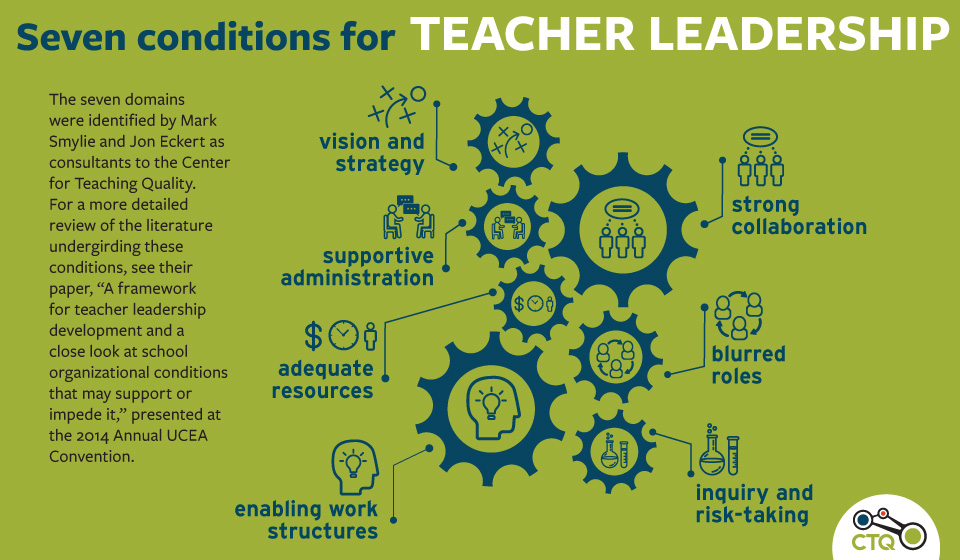

To promote teacher leadership, Berry writes that seven qualities must be in place.

- A vision and strategy for teacher leadership, “with stated goals and clear images of tasks to be done, must be in place,” Berry writes. Teachers must feel part of creating this vision in order to buy in.

- A supportive administration. “Principals must be willing to share power with teachers and must have the skills to cultivate them as leaders,” Berry writes. He points out that most educational leadership programs focus on supervising teachers, not supporting them as leaders.

- There need to be appropriate human and fiscal resources. Additionally, the personnel within schools need to think more flexibly about how to allot the dollars that do exist. SJHA receives $6,000 per pupil, but uses those resources differently from most public high schools. “Top-performing nations invest more of their education personnel funds in teachers (as opposed to administrators and supervisors), which means that more classroom experts can have opportunities to lead without leaving the classroom,” Berry writes.

- Work structures that enable authentic collaboration are crucial. While more resources help on this point, there are creative ways to stretch limited dollars.

- Supportive social norms and working relationships are key to teacher leadership. This requires a commitment to all students and respect for different areas of expertise. “All too often, policymakers develop incentives to motivate teachers and administrators,” Berry writes. “Instead, policies and programs should be in place to value teachers spreading their expertise to one another, allowing teaching to be exercised as a team sport.”

- Organizational politics must allow for blurred lines between roles. Teachers can only take on leadership roles at the expense of principals and district-level administrators. This also requires teacher unions to act more as “professional guilds” and for districts to follow the example of some for-profit businesses that are flattening bureaucracies.

- The school and system must be oriented toward risk-taking and inquiry. Just as students need hands-on applied learning rooted in inquiry, so, too, do teachers need powerful driving questions to push their work forward. “School systems must be able to interrogate themselves about the extent to which they create opportunities for teachers to learn and lead in ways that spread teaching expertise and improve student outcomes,” writes Berry.

“We’re still climbing a very big hill and we’re pushing a boulder up this very big hill,” Berry said. His organization’s strategy is to highlight exemplars of strong teacher leadership, like Social Justice Humanitas Academy, and the strong student outcomes that collaborative teacher-led schools can produce.