While we may not exactly know all the ways Shakespeare was taught to classrooms 200 or even 100 years ago, we do know that many of today’s high schoolers, increasingly engaged in the more visual communications of the digital world and the language of texting, find Shakespeare difficult to read and even more difficult to comprehend.

And while today’s teens have become more tethered to visual and digital means of communication, the teaching of Shakespeare in US classrooms hasn’t changed much, according to secondary English Language Arts curriculum specialist Kristen Nance, who facilitates resource use for one of the largest school districts in Texas.

“A lot of very traditional instruction goes along with teaching Shakespeare," she said, such as reading the plays, showing movie clips to help with visualizing, or reading parts in class to read out loud. "Getting it new and fresh sometimes is a struggle.”

Nance also said keeping kids engaged in the text can also be demanding; between understanding the archaic language and deciphering the vocabulary, and teachers trying to fill in the gaps as best they can, some kids find it a challenge to keep up.

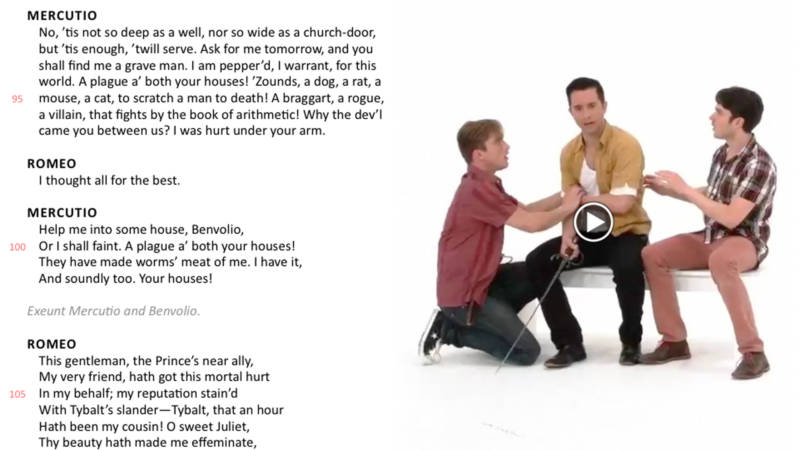

Then last year, Nance’s superior brought in Alexander Parker, who had developed a digital product for teaching Shakespeare that appeared to bring the best of two worlds together. Parker’s invention, a series of web-based ebooks called WordPlay Shakespeare, offered something Nance had never seen before: Shakespearean text alongside a performance of the play. Instead of just studying the text or watching the performance, the ebook provided a way for students to do both at the same time side-by-side, which enhanced both the reading and the watching. The performances were simple and stripped down, so as not to distract from the text, and the text had some helpful features built in to help students, like a built in dictionary, scene-by-scene synopsis, on-page annotations, and even a modern translation.