The initial School Retool research and design work was supported by the Hewlett Foundation, which is very interested in spreading “deeper learning” practices to more schools. But even when educators were inspired by models like High Tech High, they didn’t feel capable of pushing for similar models back at home. School Retool came out of a desire to support “deeper learning” leaders.

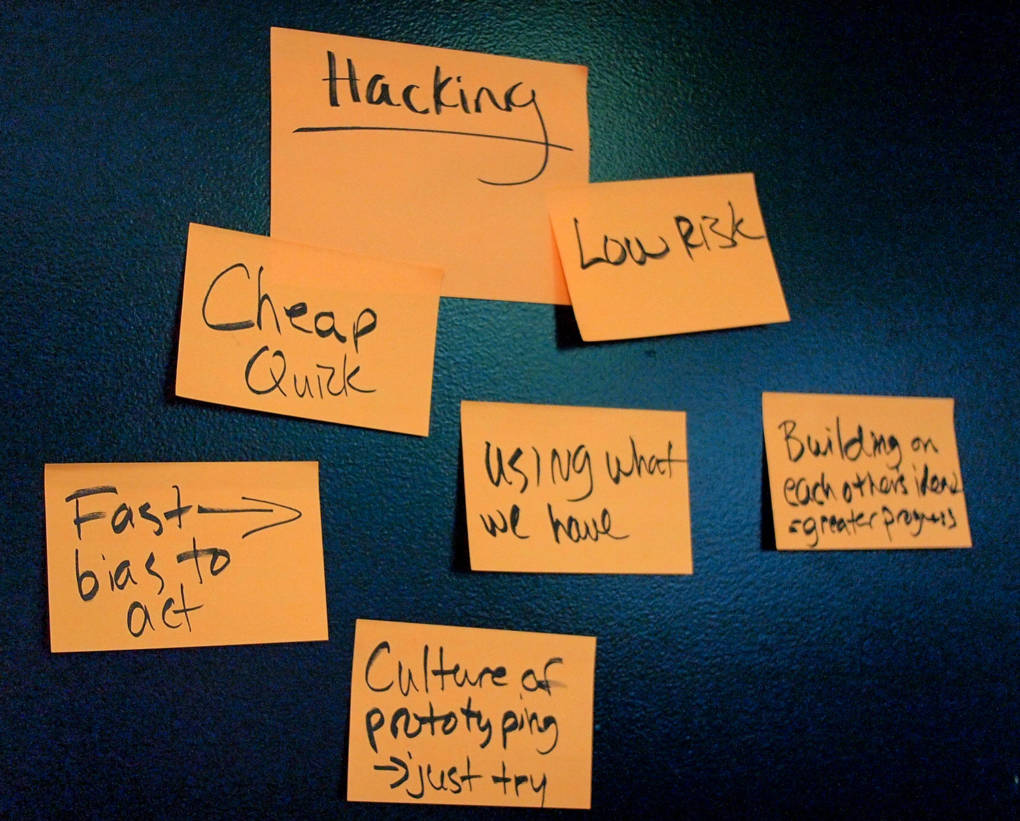

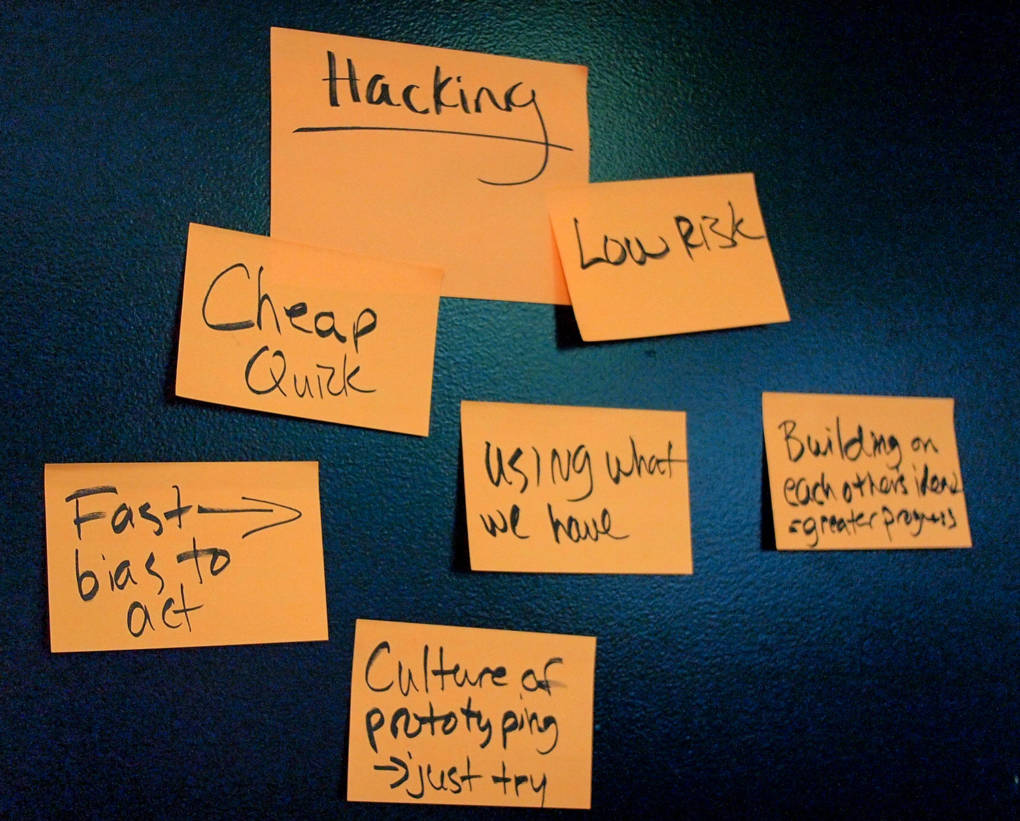

Wise thinks the most transformative part of School Retool is not the individual hacks, but rather that school leaders get the chance to experience the deeper learning process. They work on a project back at their schools, fail forward, get advice from other principals in the cohort and generally puzzle their way through something new.

“It’s a lot about getting them to move and see their mindsets in action,” Wise said. The principal is the instructional leader in the building, so modeling risk-taking, starting small and learning from things that don’t work sets an example for teachers. When principals are open to new ideas and have experienced the power of the process, they are more likely to open up those same spaces for their teachers.

“When you’re always trying to make things better and you’re trying to articulate what better is, to have a framework and a lens to think about it, it makes you feel more normal,” said Elizabeth Domangue, principal of Panorama Middle School in Colorado Springs.

Domangue has had an uphill battle. She became the principal at Panorama last year two days before the school year started. The middle school had three different principals in five years and 80 percent of Domangue’s staff were new that year, but she hadn’t hired them. Students were not doing well academically and school climate needed work.

Domangue knew it would take time to change all these factors, but she began laying the groundwork for some bigger changes. For example, she’s been trying to use the brainstorming and empathy tools she learned from School Retool to engage and empower her staff. She holds walking meetings with a small group of teachers that include new and old staff to try to think about how they can realistically build in time to make connections with kids outside of academic spaces.

“Knowing where we were, I knew if we just started with advisory without any kind of background or framework it would just be another initiative,” Domangue said. Veteran teachers even told her that advisory wouldn’t work -- they had tried it before, got no support from the administration and it ultimately failed. So rather than pushing for something the staff wasn’t ready for, Domangue kept engaging them on what could work.

They settled on something they call “Right to Read,” a silent sustained reading time every Monday morning. Teachers aren’t assessing what kids read or doing any formal debriefs. “We want it to be a time to be present in school before things start for the week,” Domangue said.

She has also been hustling to bring more funds into her under-resourced school. They recently got a violence prevention grant from Colorado University at Boulder, which will bring training around positive intervention, and will essentially fund advisory twice a week for four years. The trainers will bring toolkits and lesson plans that will help support teachers as they build their skills.

“We can’t wait for things to happen to us. We have to make them happen,” Domangue said. She encourages teachers to make connections outside the school, to write grants, and to bring their passions into the building. In her eyes that’s the only way they will be able to create a school that their community and staff deserve.

CULTURE CHANGE

To change school culture Carlin wanted to look into bringing an advisory program to his campus, but he knew that many advisories fail because the activities are too canned or there’s so little structure that it becomes a planning burden on teachers. As part of his fellowship he decided to work on the idea with a small group of staff who were also excited about the idea.

“I used the same process of going from aspirations to big ideas to small hack,” Carlin said. The aspiration was to have a Crew structure, like EL Education schools, with the big idea that every student would have a trusted adult in the building. To get there, staff members tried lots of small experiments that didn’t cost a lot of money or upend any current systems, just to see what could work. “It was important that there was that structure. It gave us a base to start from,” Carlin said.

Carlin likes challenging the stereotype that veteran teachers don’t like to change when he talks about Bill Gold, a 40-year teaching veteran on his staff, as one of his most innovative, collaborative teachers. He was one of three teachers and two counselors who began exploring what elements should be part of an advisory program.

“One component we wanted was this practice of counsel with our kids,” Carlin said. Gold decided to try and build a space where students felt safe to talk about their experience of school and their lives outside of it in his existing homeroom. “It was proof of concept. He came back to our group and said I think this should be part of what we do,” Carlin said.

Over the course of a semester the working group put together a calendar of advisory activities that fell into categories like expeditionary or project-based learning or academic support. Each small group member worked to build out lessons for a category. The planning work took place throughout the spring semester, and when school started this year Everitt Middle had an advisory program.

“I’ve heard almost unanimously our staff say that crew is something we should keep at our school,” Carlin said. That doesn’t mean there aren’t ups and downs, or that kids don’t frustrate their advisors, but fairly quickly, taking small steps, Carlin helped guide the staff toward a big change. And, he was finally able to have a whole school assembly, where every person in the building participated in a giant human puzzle.

“I think if you lead it first in a small group, then it helps the larger group see that it works, because I think so many educators are hesitant to think anything else is going to work,” Carlin said. He also acknowledges that there are always linchpin people in any organization that hold sway over others. In this case Bill Gold, the veteran teacher, was one of those people, so his excitement helped get everyone fired up.

“If it was just on me there’s no way this would happen, but with the team I had, it made it possible,” Carlin said. And the team of people at Everitt who want to be involved in work like this is growing as Carlin builds trust and staff see their ideas taken seriously.

School Retool costs $2,500 per principal, but Wise said that many of the first 18 cohorts they’ve done were sponsored by regional funders interested in investing in the school ecosystem. Both Domangue and Carlin received full or partial scholarships to participate, for example. Wise said her team priced the course at $2,500 because that’s the budget many principals have to attend conferences.