Several years ago, Waltham High School educators were trying to think of some way to enliven summer reading. They had tried book lists and they had tried letting students just read what they wanted but they were missing a deeper level of student engagement.

“We felt like we needed something different that was more meaningful,” said English teacher Emilie Perna.

They wanted a reading program that would be fun, multidisciplinary and included the community so that students would learn that reading is a life-long adventure. The educators developed a "One School, One Story" program that gives students more voice in which book gets selected during the summer and continues the dialogue with authors and members of the community throughout the year.

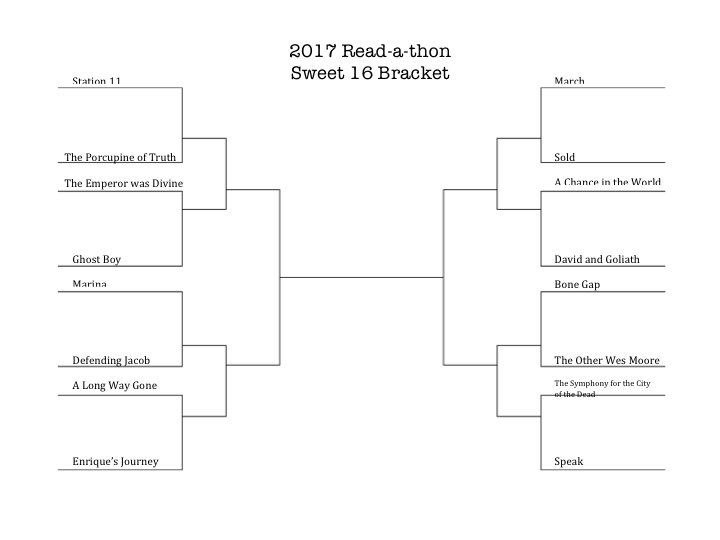

The story selection process starts in the fall, when teachers from different departments come together to read books during Thanksgiving break. They narrow a list of about 100 books to 16.

In the spring, more than 60 students participate in the 24-hour read-a-thon in the school library, where they winnow down the selections, bracket-style, to four books. By the end of 24 hours, all the students vote on the best choice out of the four books.