Cameron is no ordinary dog, and not just because he was born on Valentine’s Day. To Maggie, a first-grader at Burgundy Farm Country Day School, the Labrador/terrier mix with chestnut-brown eyes and “really fluffy” black hair who spends most days on campus is more like a friend. When Cameron is near, Maggie feels “really, really, happy,” she said. “I feel safe around him,” she added. “He’ll lay down and ask me to scratch his tummy,” she explained, because Cameron likes Maggie.

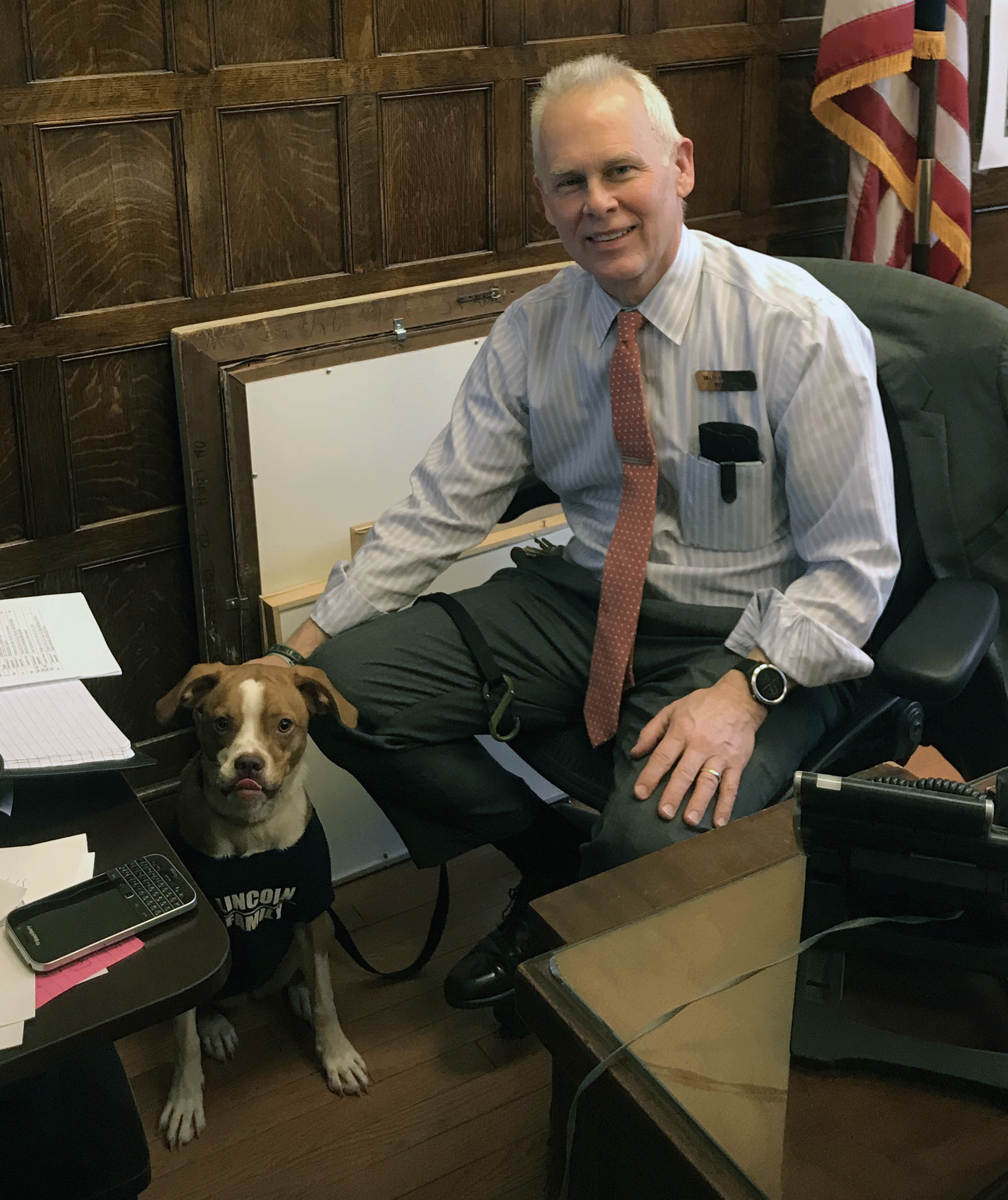

Cameron is one of a handful of dogs at Burgundy, a K-8 private day school in Alexandria, Virginia. Dogs started showing up there when the head of school, Jeff Sindler, brought his lumbering lab, Luke, to the main office building where Sindler works. After Luke died, Sindler adopted Cameron and brought him to campus, too, where the dog Maggie describes as “really cute” became a school favorite.

“They don’t care if you’re good at basketball, or a great reader, or popular,” Sindler said. “They just want to be loved—equal opportunity,” he added. Cameron and the other dogs on campus—always on a leash and with their owner—go a long way toward improving students’ social and emotional well-being, he said: They reduce tension and soothe anxiety, and elicit happy feelings from students.

“They bring out some super-basic and important emotions,” he said, and are especially helpful for children and adults who struggle in social interactions. Just as important, dogs on school grounds set a positive, welcoming tone. They help preserve the school climate that Sindler believes Burgundy embodies: one that is accepting, supportive and curious. “Dogs are one way to hold on to that atmosphere,” Sindler said, adding that “schools should be fun and exciting, and dogs can be a big part of that.”

According to research carried out at the Yale Innovative Interactions Lab, there is something distinctive about dogs that makes them so companionable. Unlike cats, parakeets or snakes, dogs have co-evolved with humans for about 30,000 years, prompting them to develop skills that make them adept at understanding social and emotional cues from humans. Dogs make eye contact, for example. They follow where a person points. When frightened, they seek comfort from humans. And according to Yale researcher Molly Crossman, who studies how humans interact with dogs, “there is encouraging, preliminary evidence that dogs might reduce stress.”