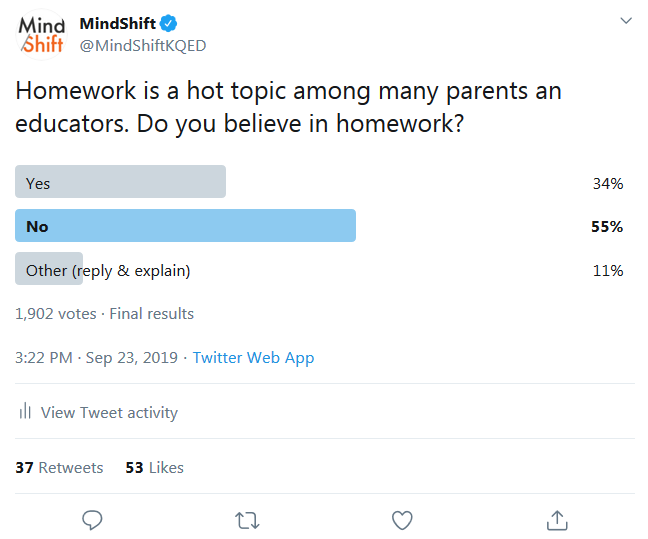

Homework is a hot-button issue for both parents and teachers. When we asked the MindShift audience about it, we got a wide range of thoughtful answers. And the results of our poll were pretty evenly split, although the “No’s” have it by a small margin (it’s worth checking out the poll on Twitter and Facebook to read about teachers' experiences with homework). That’s probably because a lot of adults are concerned that students are tired, stressed and don’t have enough downtime at home after school.

There was a pretty clear consensus among educators and parents that homework is not appropriate in elementary school. And research supports this perspective -- homework in the early years doesn’t do a lot to improve achievement. However, some argue that the goal of giving students some light assignments is to start building a habit around responsibly doing work at home.

Not for children up to age 12, as there is no research to support an achievement correlation

— Ali Baran (@AlisonBaran1) September 24, 2019

Many elementary teachers responded that reading at home should be the only homework. And research on reading supports this approach. When reading becomes a habit, kids are more likely to enjoy reading and that has all kinds of positive benefits.

I prefer to call it Learning at home rather than homework. Skill practice, reading for pleasure, finishing up a learning task, preparing for a test, conversations with family are all things that can happen at home and appropriate for kids in elementary school.

— Audrey McGregor (@AudreyMcGregor1) September 24, 2019

Many parents are frustrated that their kids’ teachers assign homework. They worry it is hurting their kids’ love of learning.

Yes but we have it in kindergarten. She’s five. She generally likes writing and reading and learning but as homework — nope. Kills the genuine curiosity and fun.

— Amanda Stupi (@Pemberly) September 23, 2019

We are dealing with teachers that assign homework every night but tell us in conferences that they don't grade it. Instead they check for completion. My daughter gets A+ after A on homework and then gets a C in the test. Teachers tell me they have too many students to grade it

— JJ (@mzzstaj) September 23, 2019

A lot of teachers who responded to this poll said they don’t assign homework per se, but if students don’t finish their work in class, they are expected to finish it at home.

I try to give students time to work in class but sometimes they need to complete assignments at home. I don’t intentionally assign work for them to do exclusively at home.

— Dustin Potter (@mrpottercb) September 23, 2019

I voted other because I do believe in giving engaging tasks that Ss WANT to do for homework, but homework for the sake of practice can be done in class and represents an equity issue when taken for a grade and Ss don’t have support at home

— Jenny Peters (@jennypmathed) September 24, 2019

The research on homework and cognitive learning tells us that some kinds of homework are more useful than others, although parental frustration about “poor quality” homework abounds. Many teachers responding to the poll said they don’t believe in "busy work," but some definitely see value in practicing skills learned in class.

Students need to learn the discipline of sitting and working at home but I dislike homework that requires more than 10 repetitions of the same skill. And error correcting work is good homework too.

— Alicia Warnick-Ellis (@Alitig1) September 23, 2019

Cognitive science tells us one way to make homework more effective is to space out practice. The brain remembers things better when there are multiple opportunities to practice in small chunks over time. Designing homework that doesn’t leave topics in the past, but continues to resurface them over a semester, is powerful for retention.

Well-crafted homework for high school students (no busy-work) is essential for some courses. For elementary students - just no. If they just read at night, that would be great (but no reading logs).

— Amber Counts (@mrscounts) September 23, 2019

Research tells us another way to make homework more meaningful is to force students to retrieve information from their memory with low-stakes quizzes. When we first learn something, the memory we’ve formed with the information is weak and easily forgotten. But every time we pull it up without looking at notes, it gets stronger.

I believe in suggestions for home reinforcement and acceleration. The WORK should be done at school!

— Brian Moore (@BMooreAP) September 23, 2019

Some research shows that in the older grades homework can be helpful. Some studies show a correlation between homework and improved unit test results. But more is not always better. Research also shows that higher-income schools often assign more homework.

Written homework? No. But as a band teacher who sees her students only 2 or 3 times a week with no time for sectionals or pull-out lessons, I expect my students to practice at home.

— Ms. Tucker (@ExpatMusicEd) September 23, 2019

Instead of giving students a lot of practice on the same set of skills, homework with a variety of questions that mix up the skills required to solve them is more effective. Cognitive scientists call this “interleaving.” When students can’t tell in advance what kind of knowledge or problem-solving strategy will be required to answer a question, their brains have to work harder to come up with the solution, and the result is that students learn the material more thoroughly.

It exists so it doesn’t matter whether I believe in it. Should it exist? Yes, but not as rote drills or to teach obedience. It ought to be expansion & exploration, and developed across subject areas, so that there’s just one assignment not one for each subject.

— 🧱House🏳️🌈 (@architek2ra) September 23, 2019