Debbie Barkley held her string tightly and directed the teachers around her to tug theirs downward as they maneuvered a rubber band around the sides of a red Solo cup. “This is so frustrating,” Barkley said when one of the cups fell over, not for the first time. “My fifth graders would be yelling at each other at this point.” A few minutes later, when the group succeeded in stacking several cups in a prescribed arrangement, teacher Ami Patel-Hopkins, exclaimed, “Oh, I love my group!”

That range of emotions is what Kathleen Tsai, a chemistry teacher who facilitated the exercise, expected. “It’s frustrating but then you have a sense of fulfillment,” she said during a group reflection at EduCon 2020, a school innovation conference. “The amount of frustration I feel when I do this is the same as my students feel when they’re doing algebra. I’m sweating when I’m stacking cups; they’re sweating when they’re doing homework.”

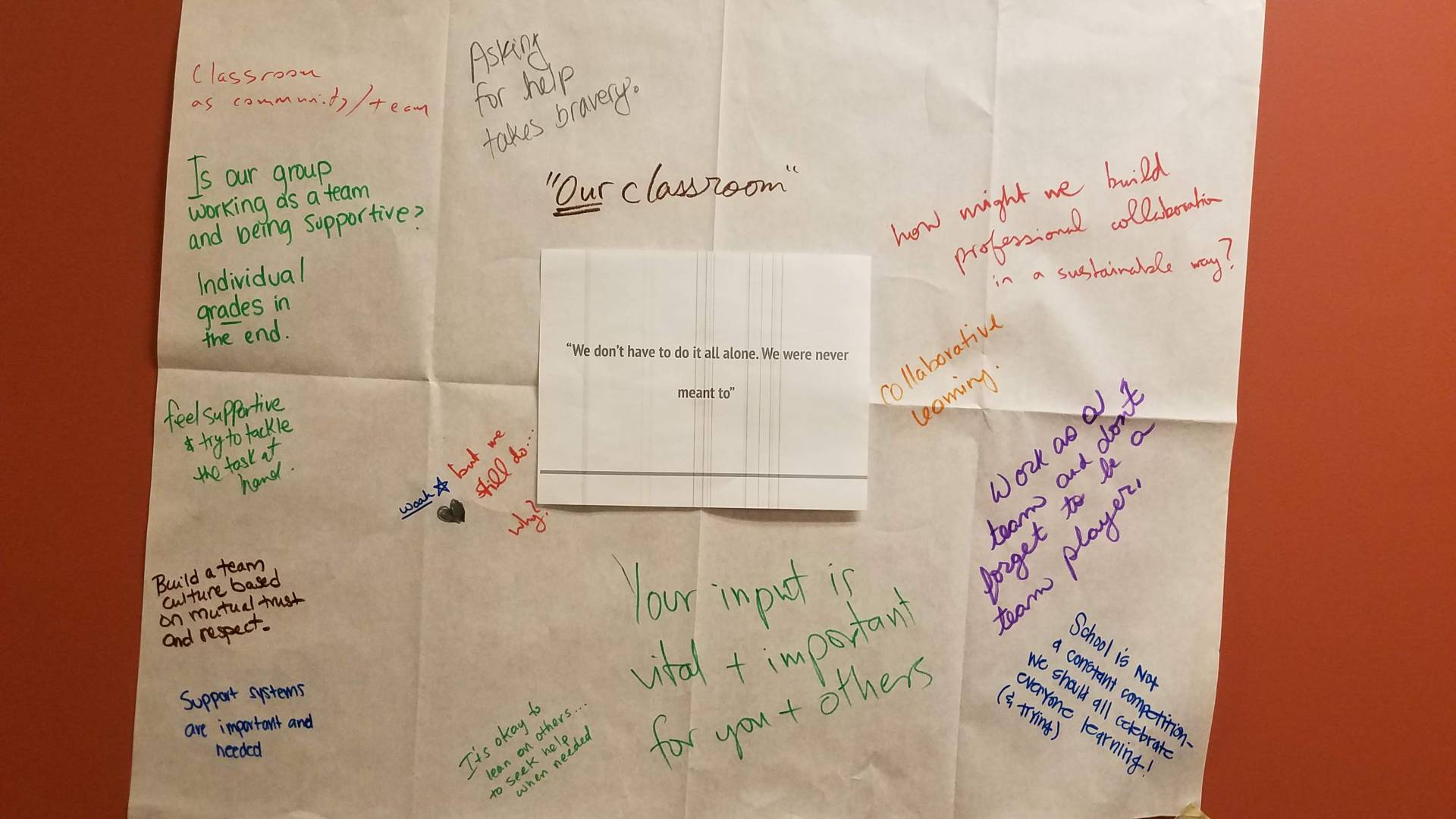

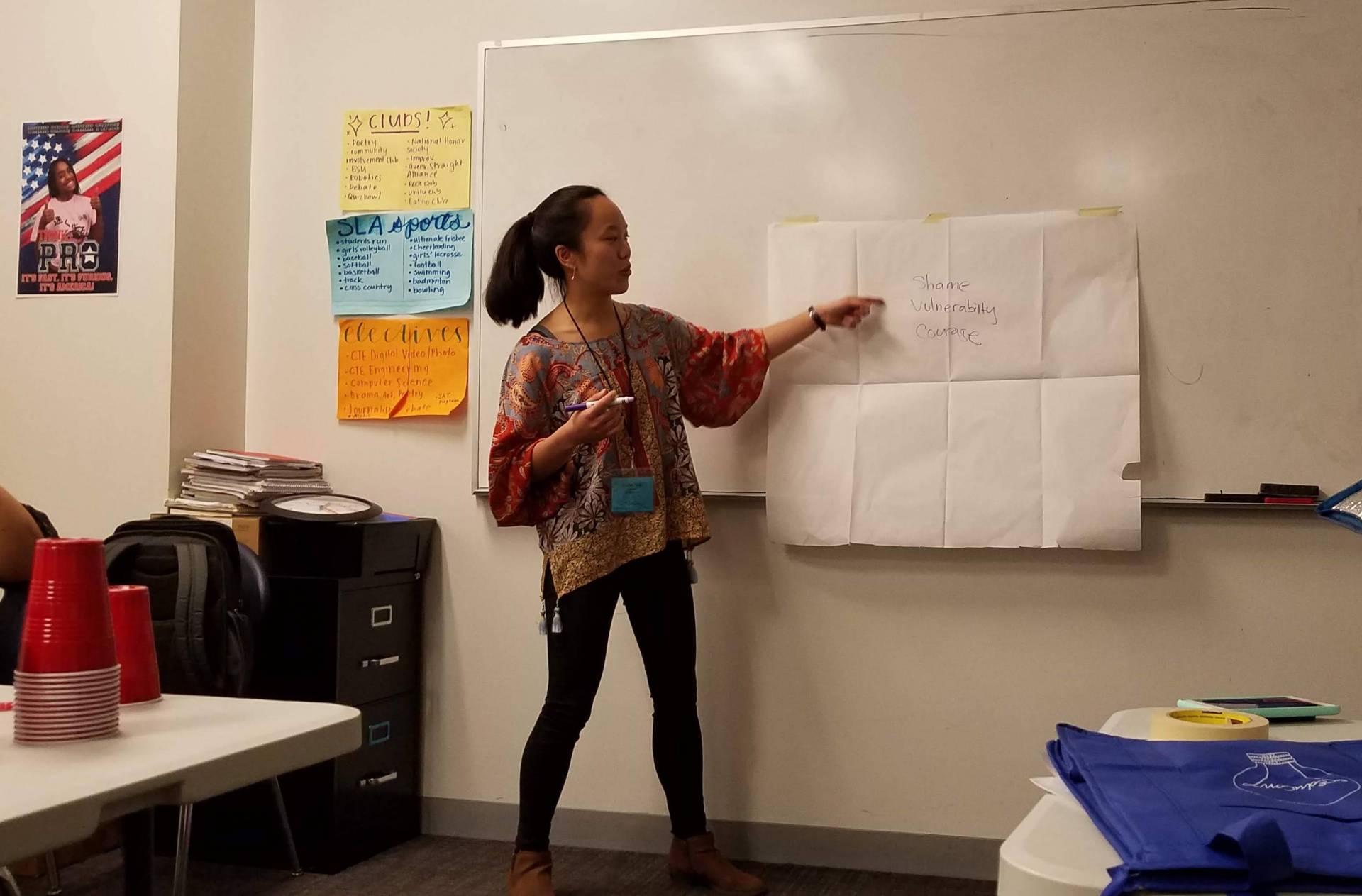

Empathizing with students’ emotional experiences was a central component of the workshop that Tsai led on cultivating resilience in science class. Educators have increasingly focused on the role of social and emotional learning in school culture and student success, but participants at Tsai’s session said the opportunities to teach such skills arise more naturally in humanities courses. At the same time, they agreed that collaboration and the ability to persist through failure are critical in science. Through Tsai’s exercises and reflections on their classroom experiences, the group discussed how to strengthen communication and build resilience among their students.

Start Early

Devoting time early in the year to cooperative games allows students to practice healthy communication and conflict resolution before academic content is in the mix. Tsai, who teaches at Science Leadership Academy Beeber — a project-based learning school — does the cups activity with her students in the first week of class. By trying it themselves, the EduCon participants experienced some of the emotions that students might during group work. In the discussion, one teacher said she found having clear roles helpful as problems arose. (Before the activity began, group members elected to be communications manager, resource manager, task manager or group manager. Tsai provided explicit descriptions for each role.)

Tsai pointed out that when one of the groups asked for tips, she told them to figure it out, rather than giving them the answers. Whether with cups or lab work, students often hate that response, Tsai said, and several teachers shouted “yes!” in agreement. Overcoming such hurdles in a low-stakes cooperative game creates a foundation of resilience that can be strengthened as students face similar challenges when science content and grades are involved.