Bryan Shaw does not teach history the way he was taught. The wars, the presidencies, the social movements — memorizing those details is not the end goal. Instead, learning about historical people and events is a pathway for students to develop historical thinking skills, such as looking for commonalities, identifying causes and consequences, and distinguishing progress and decline over time. When his school closed because of COVID-19, Shaw wanted to continue that work. He also knew that standard history content would feel even more distant to teenagers facing a global pandemic.

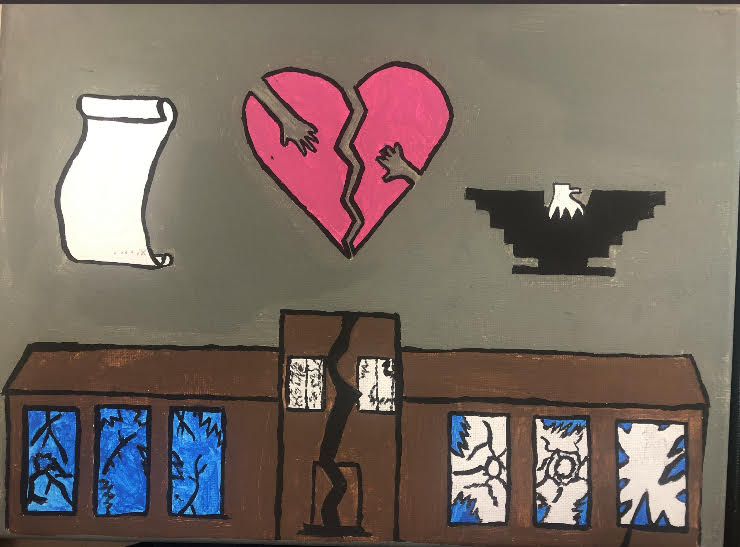

“So many of our students are worried about survival right now. They don’t care about the Cold War,” said Shaw, who teaches at Ygnacio Valley High School in Concord, California. So he created an assignment in which students themselves would be the historical actors: keeping a pandemic journal. He instructed students to observe changes in the community, country and world in response to the spread of coronavirus. He provided questions as jumping-off points and encouraged students to to chronicle their experiences using poetry, sketches, videos or other mediums along with traditional diary entries.

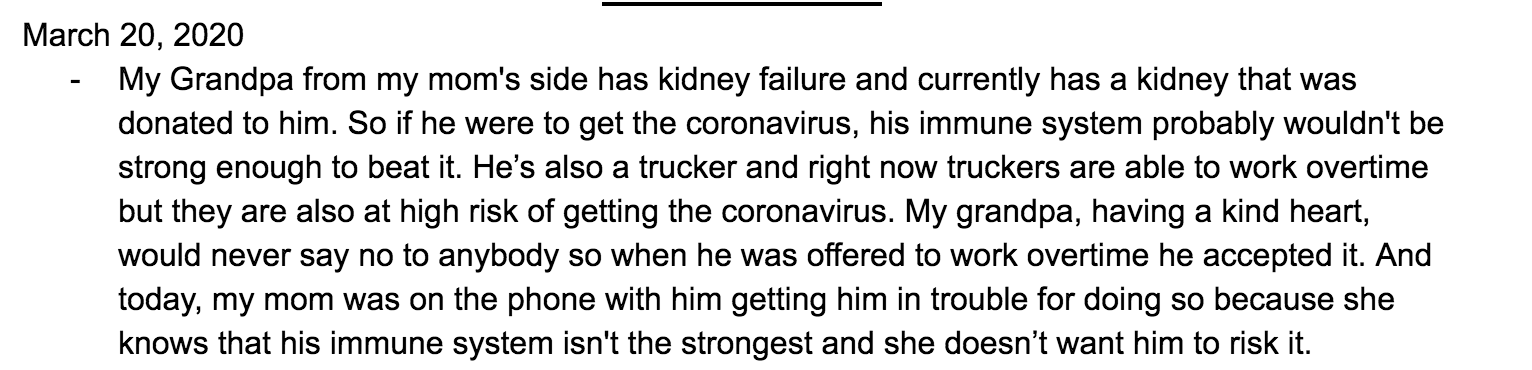

Once per week, Shaw’s students email him pictures from their journals. At first, students focused on the pandemic’s immediate effects on their lives. Seniors, for example, wondered, “Am I gonna come back to school? Am I gonna graduate?” As weeks passed, entries reflected students’ growing recognition that they were part of a bigger story. That’s where those historical thinking skills started to appear. They pondered causes and consequences of politicians’ decisions and analyzed their personal experiences as part of socio-political systems. “The students are thinking about their day-to-day in the larger context of the world, which is pretty cool to watch,” Shaw said.

A viral assignment

After developing the journal assignment, Shaw shared it with the University of California Berkeley’s History-Social Science Project. The project’s director, Rachel Reinhard, distributed the lesson through a statewide network, and it quickly spread quickly beyond California. The original lesson has been adapted into multiple languages and modified for different grade levels and specific fields of history.

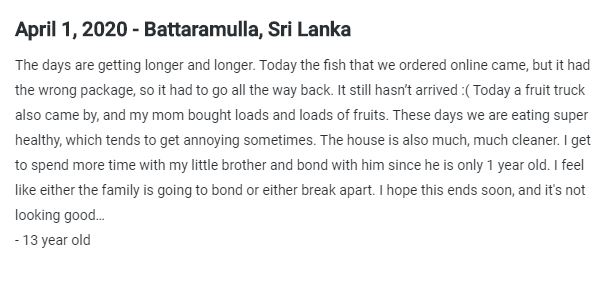

Chelsea Prehn, a seventh-grade teacher at the Overseas School of Colombo in Sri Lanka, is one of the teachers who spotted Shaw’s idea and ran with it. Rather than individual journals, she asked her students to chronicle their experiences on an interactive timeline she created in collaboration with other international educators. Entries show the pandemic and its effects hitting countries and states at different times, but common threads, such as boredom, appear. “Reading that another kid on the other side of the world is facing the exact same situation and feelings about that situation as you are can be a very powerfully uniting experience,” said Prehn.

By contrast, young people’s absence from primary source documents can make it hard for kids to feel connected to historical events, said Shane Carter, program coordinator for UC Berkeley’s Office of Resources for International and Area Studies.* Carter and Reinhard are collecting coronavirus journal entries and assessing the best way to archive them. Their goal is to make them available and searchable for future historians and students to help make sense of what happened during this global event.