Design processes typically start with an average population in mind. As a result, “a lot of people who are at margins get left out, or we worry about them ‘catching up’ to the design,” says MIT professor of civic design Ceasar McDowell in a 2014 video by the Interaction Institute for Social Change. McDowell likens that approach to staking a large tent with poles at the center. When a strong wind comes, it will collapse. If, instead, the tent is staked from the outside, it is more likely to withstand the weather. That’s what McDowell calls “design for the margins.” He gives another example, this time involving humans: sidewalk curb cuts. Originally created to help disabled World War II veterans navigate urban areas with wheelchairs, curb cuts became a legal requirement under the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

“Now who benefits from that?” McDowell asks. “Take your average day walking down the street, and you’ll see a little kid riding his tricycle right across down the curb cut and across the street. Someone pulling their grocery cart. Someone pushing their baby. You’ll even see runners making that run nice and smooth, they don’t even have to jump off the curb to do it. But where did it start? It started by taking care of and paying attention to someone — some group of people who were at the margin of society to make sure they were taken care of, and in turn we were all taken care of.”

The idea that creating equitable and flexible design can benefit all members of society undergirds universal design, a concept developed by architect Ronald Mace. Rooted in the disability rights movement, universal design is typically applied to products and the built environment, but the principles offer a valuable way to reimagine educational spaces, particularly during the coronavirus crisis. With the rapid switch to distance learning this spring, schools struggled to serve students who are at the margins for a variety of reasons, from disabilities to homelessness to poverty. Recently, as schools planned for reopening, educators attending a design challenge hosted by University of California Berkeley’s Professional Development Providers used universal design principles to think creatively about how schools might function in the fall.

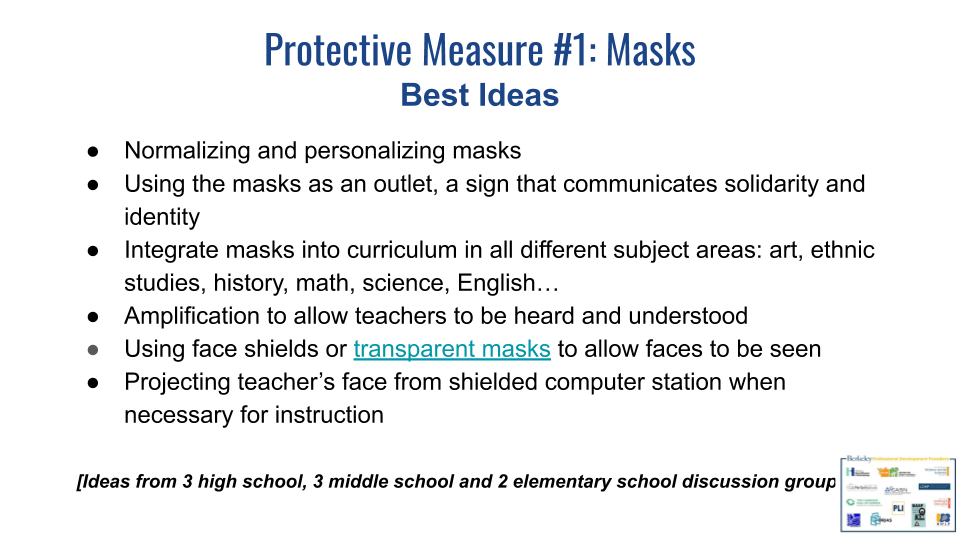

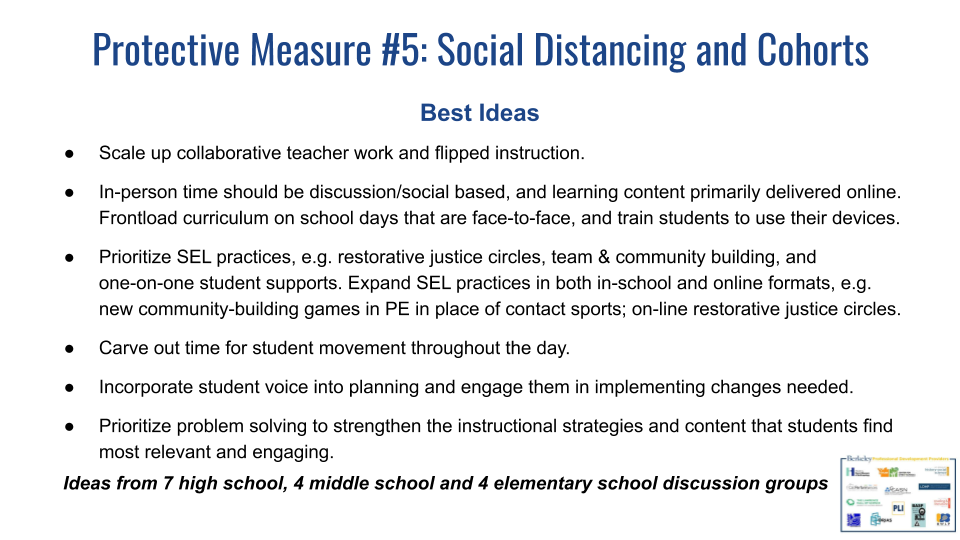

Before the event, Shane Carter, one of the challenge coordinators, asked participants to consider two real students whose full and equal participation in school was limited by the mismatch between their circumstances and traditional structures and processes. During the event, attendees heard about school reopening experiences from teachers in multiple countries. Then, in virtual breakout groups, teachers brainstormed what resources and strategies they would need to implement new health-protective measures such as masks, ventilation, health screenings, sanitation, cohort learning and social distancing. They were encouraged to keep in mind the two students they had identified to ensure that they designed classroom and school practices that were “capacious enough and flexible enough” for all students.

In one breakout room for elementary educators, participants discussed the merits and drawbacks of masks and face shields and how young kids might respond to each. When a teacher said that one of her students was hard of hearing and needed to read lips, someone else said she had seen transparent masks designed for that purpose. Another teacher said that such masks could be helpful for all young kids as they’re learning nonverbal communication. They could also help teachers better understand students while wearing masks. From there, the group’s ideas started rolling. What if older kids in the district made transparent masks as part of an art or technology course? That could be a boost if time in those subjects is reduced due to rotational schedules, one teacher noted. Another pointed out that it would ensure all students had masks, regardless of family income.