That’s a particular advantage during the COVID-19 outbreak. Gilbert said he felt good about existing bonds among students and with teachers for incoming sophomores and seniors: “Even if it’s distance learning they’ll be able to get into a space where they are very comfortable with each other and they can talk.” Johnson, too, felt positive her class could start strong despite the pandemic. She already knows, for instance, several students in class have mastered parts of the third-grade math curriculum, so she won’t have to spend weeks assessing those skills.* She also knows various instructional and behavioral strategies that have succeeded and failed with each student so she won't have to build from scratch. “We can get started on the very first day of school.”

Building Community and Listening Deeply

The benefits of looping may derive in part from increased familiarity with peers, as well as with teachers. According to Gilbert, educators must play a proactive role in all of those relationships. Anybody can be a “purveyor of content,” he said. “You have to buy into the fact that you are also a liaison to the family, that you are an emotional support for the student, that you’re creating a community that lasts over time, and then you start to see those benefits of the students seeing themselves as a community that they can rely on.” At Hillsdale, community-building happens in class and in weekly advisory periods, during which students might explore career paths, share food and stories or play a game outside. This fall, with Hillsdale likely opening to smaller groups of students, Gilbert said the school will prioritize getting freshmen and juniors on campus since the sophomores and seniors already have a foundation of trust within their cohorts.

While some educators see community-building activities as an “extra,” Gilbert said that the bonds that form within cohorts have “a significant impact on their ability to learn and their sense of emotional safety.” For example, his staff does not see the same conflicts with group projects that are typical in most high schools. The trust that forms among looping classes can also create space to tackle tough topics. In the wake of this summer’s protests against racial injustice, Gilbert said he’s confident that his staff will be able to facilitate meaningful conversations on race. Johnson, too, said she’s excited to build on the foundations of anti-racism that she already laid with her third-graders.

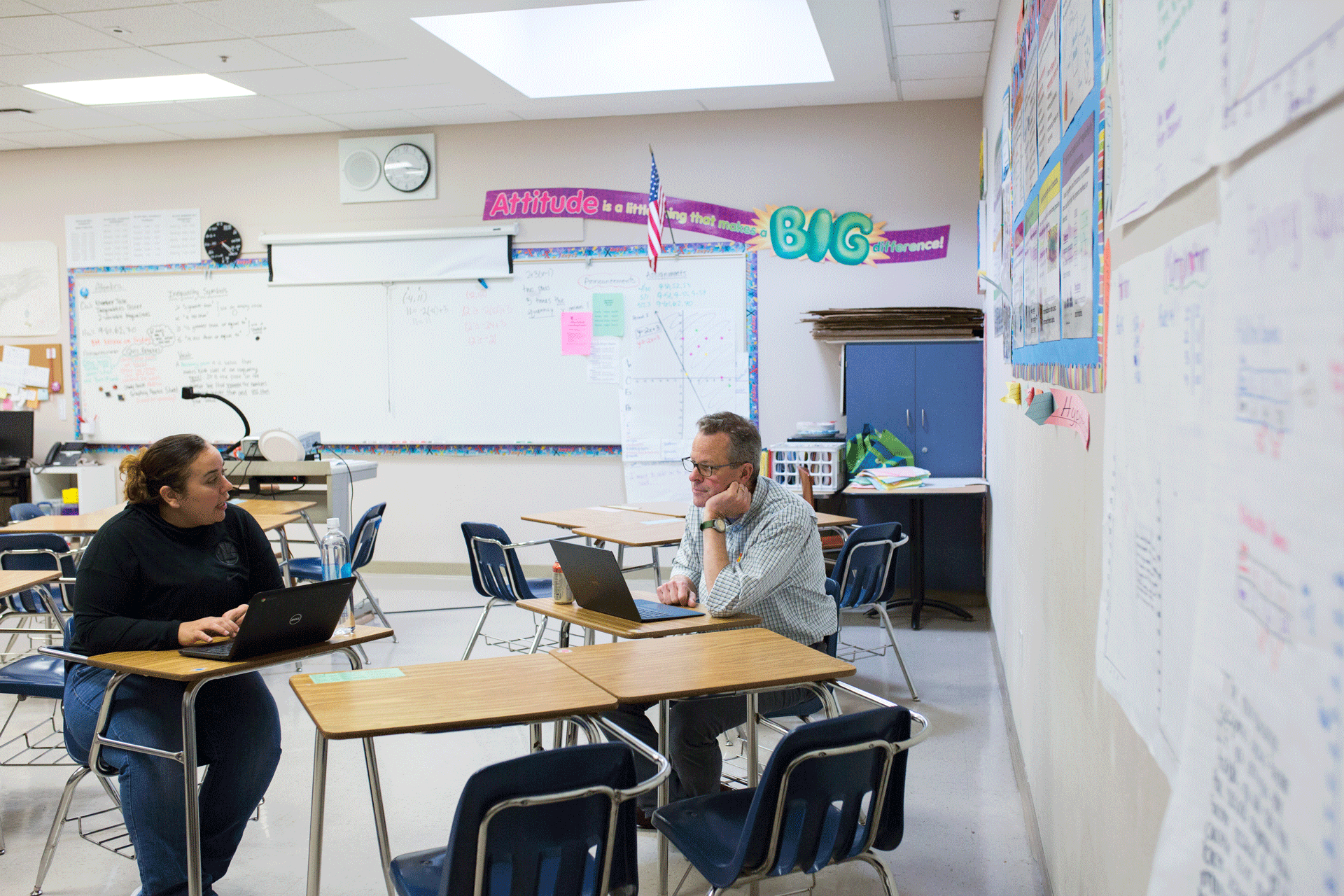

Of course, looping is not a magic wand. Reaping its rewards requires listening deeply to kids and their caregivers — “not to hear what I want them to say, but what they are actually communicating,” said Johnson. When teachers do that, the learning is not unidirectional. One of the things Johnson has learned from her students, for instance, is “to confront my previously unconscious gender bias to be a more effective teacher of boys, specifically Black, Indigenous, boys of color.” Johnson also said teachers must be conscious not to relax into static views of themselves or their students. In the entryway to her classroom, more than a hundred photos cover the wall. When the building is actually open, her students marvel at the snapshots of their former selves, proclaiming “We were so little!” or pointing out big events, such as the first time they touched the inside of a pumpkin. If it sounds like being inside someone’s living room, that’s intentional. While many educators are wondering what school will look like in a few months, Johnson’s vision is clear: “continuing to grow together as a family.”

*Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly identified how many students mastered the math curriculum. We regret this error.