It’s unclear when school buildings will reopen across the U.S., but when they do, it won’t be education as usual. Coronavirus precautions may include wearing masks, spacing desks six feet apart, restricting hallway movement and eating lunch inside classrooms. Students will be reconnecting with peers after months of limited contact, and some will still be dealing with the stress caused by the pandemic’s medical or financial impact on their families. This unusual brew of circumstances has some educators worried about more than just the spread of germs. Will enforcement of new health and safety measures lead to increased disciplinary actions, further disrupting students’ education? And if so, will it exacerbate the disproportionate punishment rates that Black students and students with disabilities already experience?

“I can just see people coming back and being like, ‘No, these are the rules. You violate the rules and this is what’s going to happen to you,’” said Michael Essien, principal at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Academic Middle School (MLK) in San Francisco. That rigid approach is not how he plans to lead. Perhaps that’s because he has already been through the mill to find an effective way to rein in behavioral issues at his school. Prior to his arrival at MLK and during his first few years as assistant principal, the climate was chaotic, Essien acknowledges. The school had one of the highest suspension rates in the region and so many of those suspensions were for Black students that the state was monitoring the issue. When he moved up to the lead principal role, he implemented a system called “push-in” services, in which support staff come to classrooms to de-escalate and resolve problems, rather than yanking students out. The introduction of push-in services has transformed the learning environment and led to a big drop in disciplinary actions.

But it’s not just that track record that gives Essien confidence about managing discipline during the pandemic. It’s something deeper that he has promoted as a school administrator: student voice. When students return to MLK, they won’t immediately be lectured about masks and other new rules. “It's going to be a conversation,” Essien said. “When we come up with what we're going to agree upon, then that will be what we will implement.” That doesn’t mean students can reject state or district mandates. MLK staff will be up front about non-negotiables, but Essien said that listening to young people’s ideas about how to handle the changes will give students agency and increase their investment in the solutions. “(School is) going to be a lot different. I have feelings, and I know they're going to have feelings,” he said.

Student onboarding

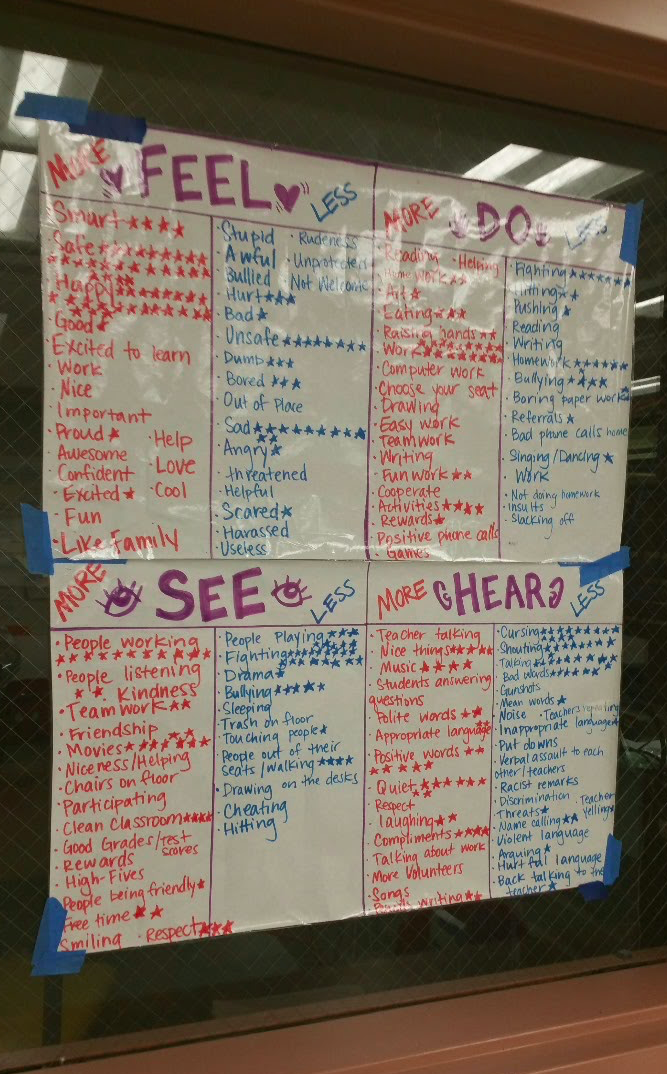

Under normal circumstances, during the first four weeks of school, MLK students would spend homeroom and the elective period doing onboarding activities that range from social-emotional lessons to discussions about sexual harassment to outdoor games. Though the logistics of this year’s onboarding will depend on when and how the school building opens, Essien said that one particular activity will be critical for a positive return. That exercise, which comes from the Pax Good Behavior Game, is called a “See, Hear, Feel, Do” chart. To kick it off, a teacher asks students to envision their dream school — the place where they would be the happiest learner. Students individually brainstorm what they would see, hear, feel and do in that school. They take three minutes of silent writing time for each verb before sharing their ideas in small groups and with the class. Next the teacher asks them to envision the worst school and come up with the things that might happen there. By the end of this process, the class creates a large chart listing out the things they want to experience more and less of in their own school. Some examples from previous students include wanting to feel safe and not threatened, choose their own seats and do less busywork, see more teamwork and less trash on the floor, and hear more music and fewer racist remarks.

The See, Hear, Feel, Do charts created by homeroom sections are combined into one for each grade level. Essien said that in the new school year, this will be the first step in “co-constructing what discipline is going to look like around us.” Teachers and administrators refer back to the charts throughout the year, so it’s important that the ideas are student-driven. “The whole point of this is we need to have kids give their perspective, because (then) it's a different conversation. Then the adults in the building, we’re not disciplining you, we’re reminding you of what you wanted.”