Middle grade: Farah Rocks Fifth Grade by Susan Muaddi Darraj, Clean Getaway by Nic Stone, Ways to Make Sunshine by Renée Watson

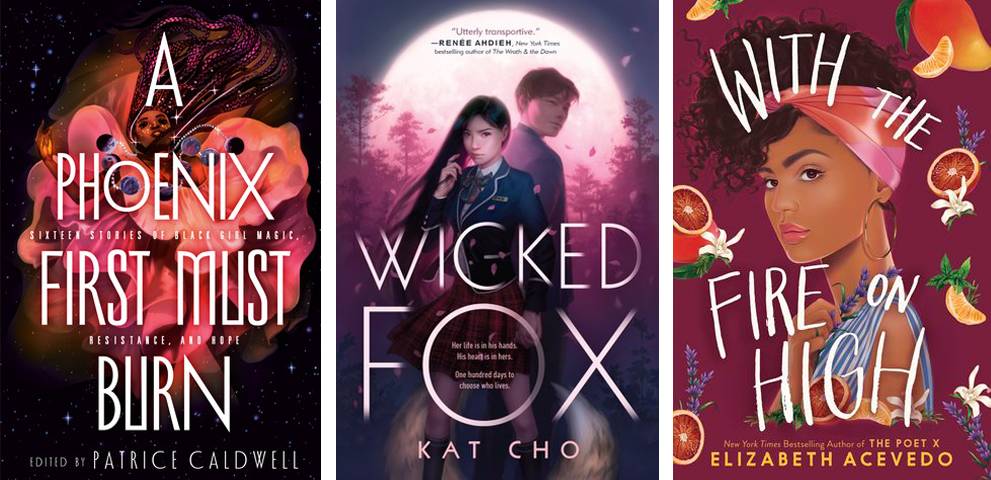

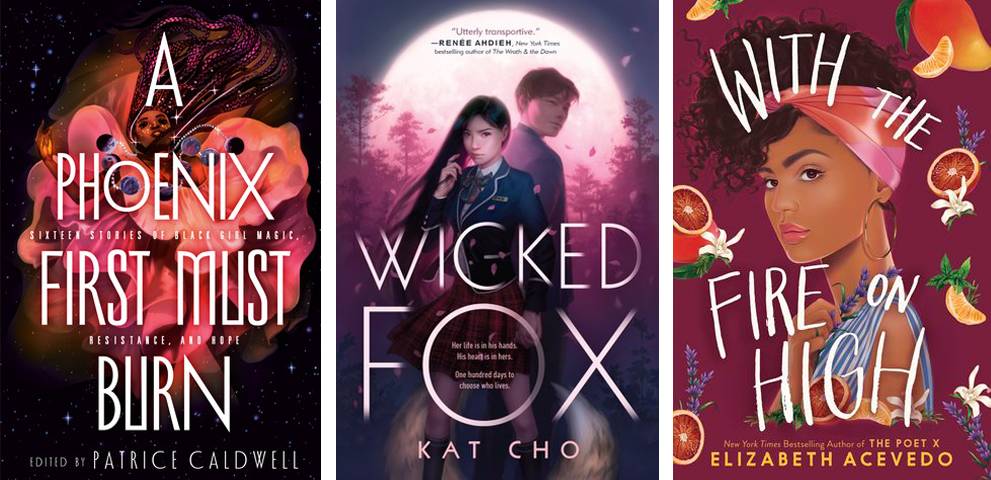

Young adult: A Phoenix First Must Burn edited by Patrice Caldwell, Wicked Fox by Kat Cho, With the Fire On High by Elizabeth Acevedo

Surface-level Diversity

In February, Barnes & Noble canceled a plan to release twelve classic novels with covers featuring protagonists of color after critics called the promotion “literary blackface.” In a live episode of the “Book Friends Forever” podcast, author-illustrator Grace Lin said it is tempting for picture book creators to make a similar mistake. “I want to make sure the (diverse books) that are created are ones that are not just done just because people are saying ‘Ah, we need diversity! Let’s throw some dark skin on that character!’ That’s very shallow and a little insulting,” she said. By showing people from marginalized groups with texture and specificity, books such as Lin’s Caldecott-Honor-winning A Big Mooncake for Little Star can move classroom and library collections beyond token diversity.

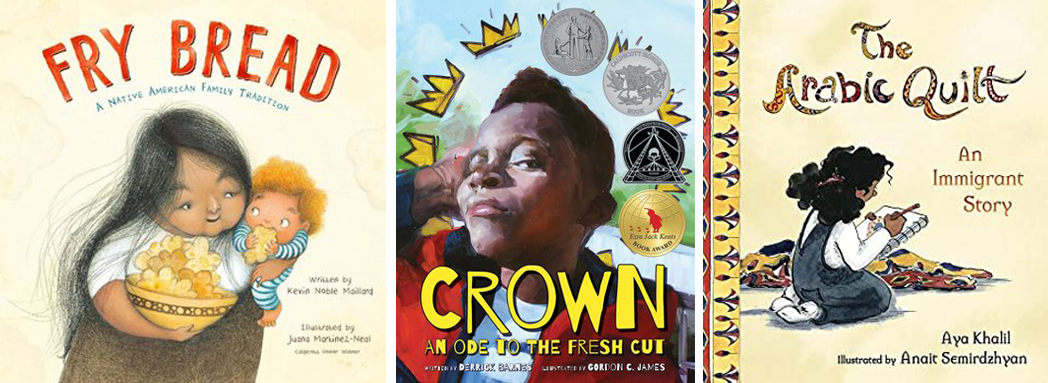

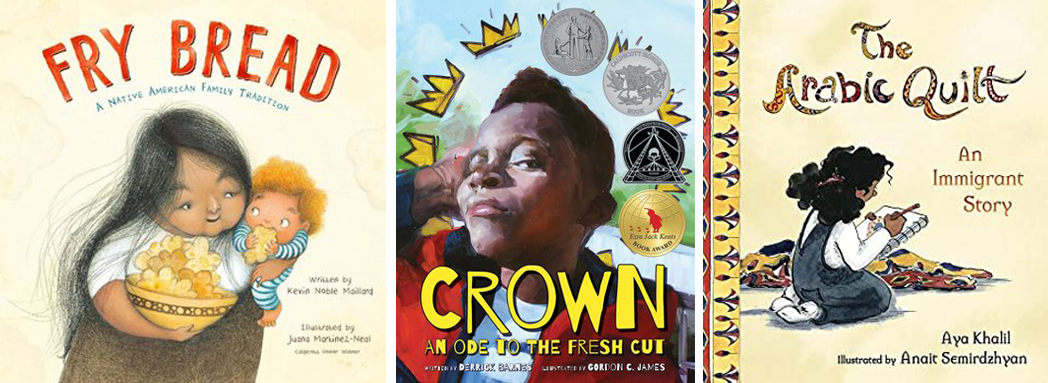

Picture books: Fry Bread by Kevin Noble Maillard and illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal, Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut by Derrick Barnes and illustrated by Gordon C. James, The Arabic Quilt by Aya Khalil and illustrated by Anait Semirdzhyan

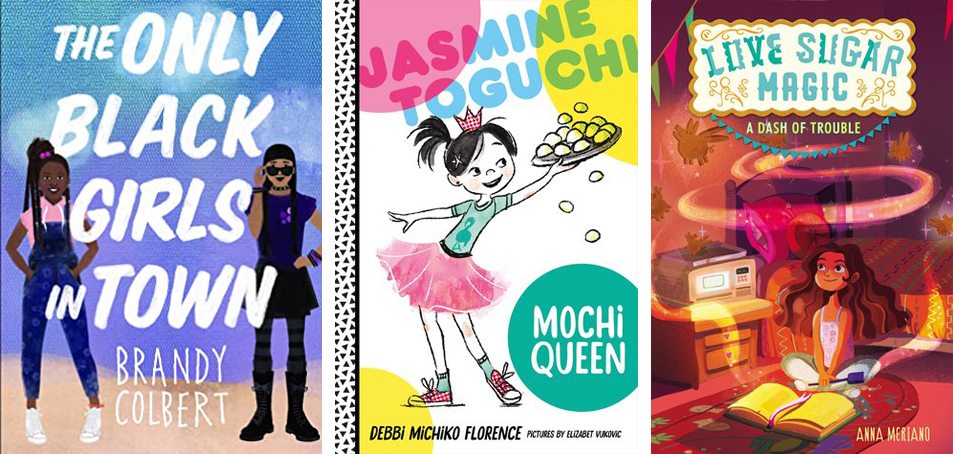

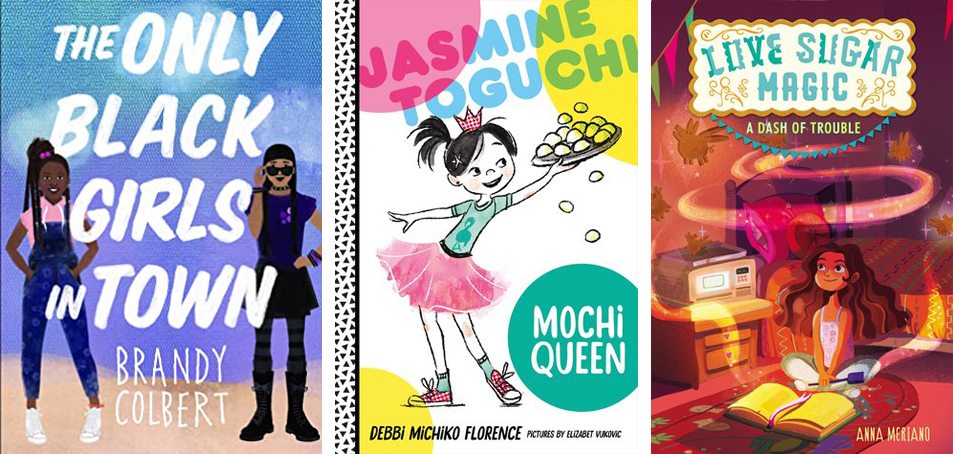

Middle grade: The Only Black Girls in Town by Brandy Colbert, Jasmine Toguchi, Mochi Queen by Debbi Michiko Florence, A Dash of Trouble by Anna Meriano

Young adult: The Downstairs Girl by Stacey Lee, Let Me Hear a Rhyme by Tiffany D. Jackson, Hearts Unbroken by Cynthia Leitich Smith

Ignoring Intersectionality

Three decades ago, legal scholar and civil rights activist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” as a way of examining how courts failed to account for the overlapping forms of discrimination faced by Black women. Today, the term is used more broadly to refer to the way race, class, gender, sexuality and other characteristics overlap and shape individuals’ experiences. “We like to think about people being one thing or the other when you can be Asian and queer and an immigrant,” said Martin, the University of Washington professor. While a decade ago it may have been hard to find books by and about people whose identities sit at those types of intersections, that’s increasingly less true, Martin said. “You can find those books if you are looking.”

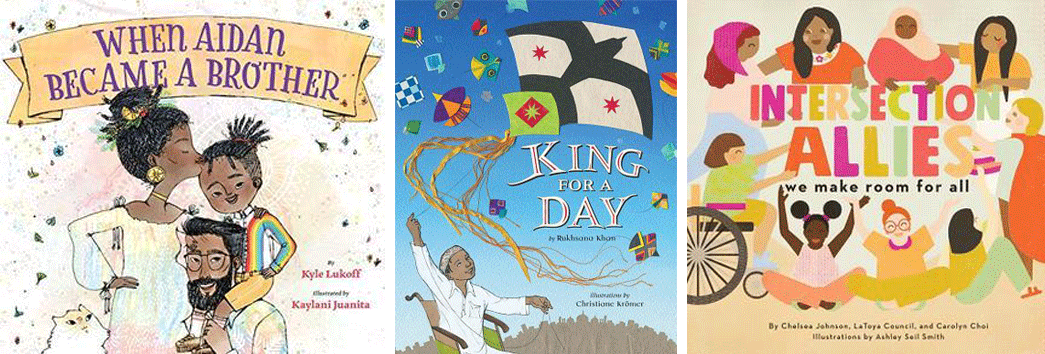

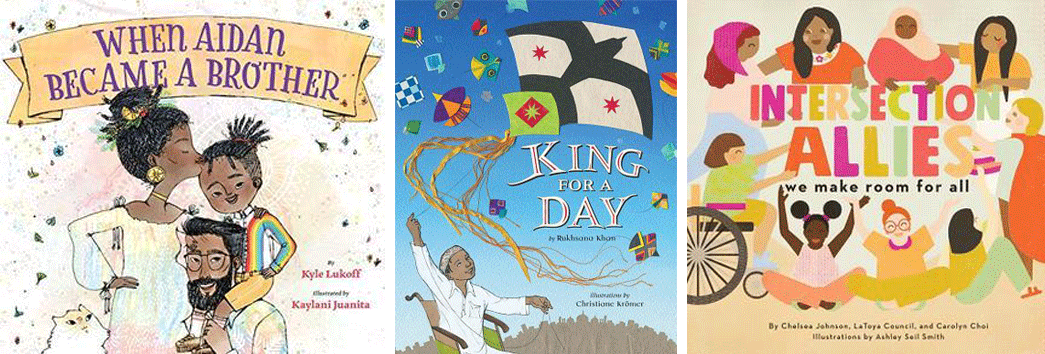

Picture books: When Aidan Became a Brother by Kyle Lukoff and illustrated by Kaylani Juanita, King for a Day by Rukshana Khan and illustrated by Christine Krömer, IntersectionAllies: We Make Room for All by Chelsea Johnson, LaToya Council and Carolyn Choi and illustrated by Ashley Seil Smith

Middle grade: Harbor Me by Jacqueline Woodson, Mia Lee is Wheeling Through Middle School by Melissa and Eva Shang, The Bridge Home by Padma Venkatraman

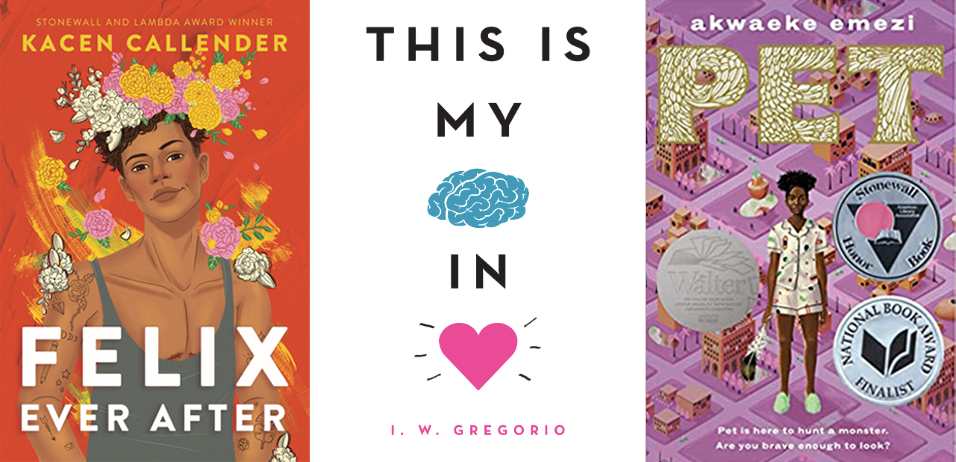

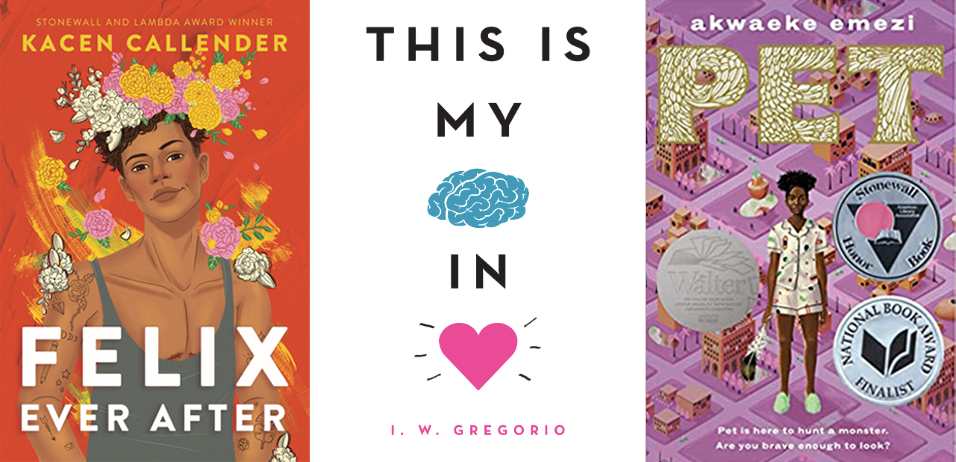

Young adult: Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender, This is My Brain in Love by I.W. Gregorio, Pet by Akwaeke Emezi

Sidekick Syndrome

Author Christina Soontornvat was an adult the first time she saw someone who looked like her on a bookshelf. Perusing a bookshop, she came across Millicent Min, Girl Genius by Lisa Yee, originally published in 2004. “I remember just being like ‘Oh my gosh, that is an Asian girl on the cover of a book all by herself? Not like the Baby-Sitters Club, like Claudia on the Baby-Sitters Club, where she’s just one of the baby-sitters,” Soontornvat said in a panel discussion hosted by the Asian Author Alliance in May. “It was one of those things where you don’t even know what you wanted or were lacking until you see it.” Like Soontornvat, many authors of color and indigenous authors today say that they either didn’t see themselves represented in books as kids or when they did, the characters were sidekicks, stereotypes or both. Through their own books, these authors offer portrayals that center and celebrate kids from many identities.

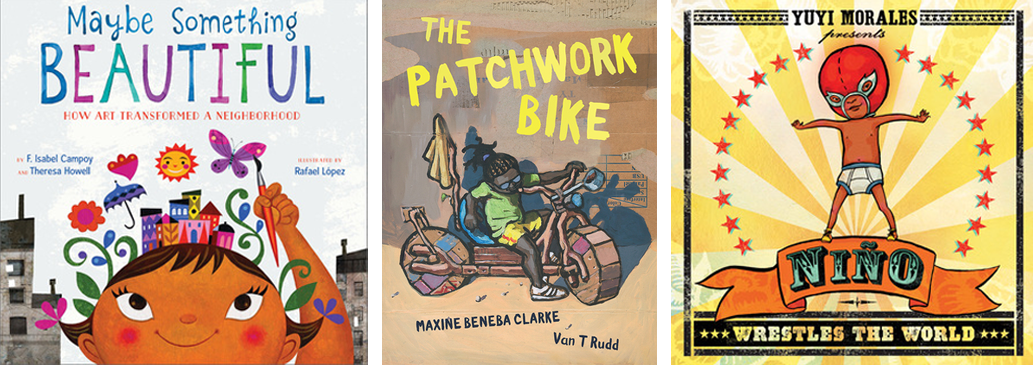

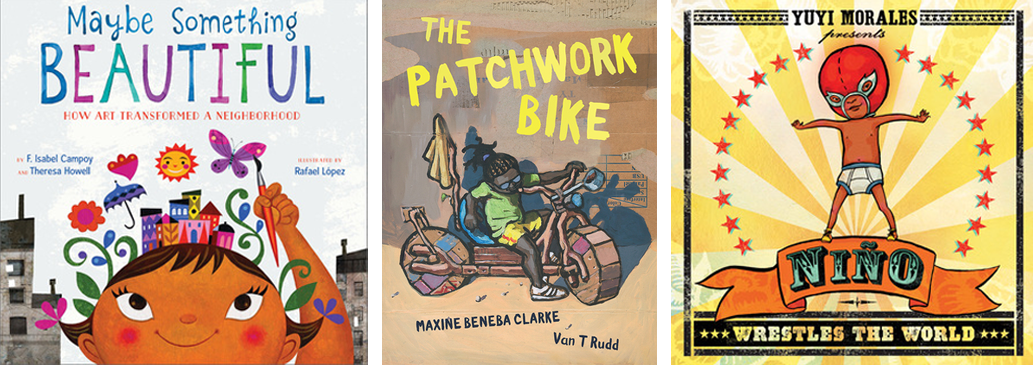

Picture books: Maybe Something Beautiful by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell, illustrated by Rafael López, The Patchwork Bike by Maxine Beneba Clarke and illustrated by Van T. Rudd, Niño Wrestles the World by Yuyi Morales

Middle grade: Sal and Gabi Break the Universe by Carlos Hernandez, Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky by Kwame Mbalia, Dactyl Hill Squad by Daniel José Older

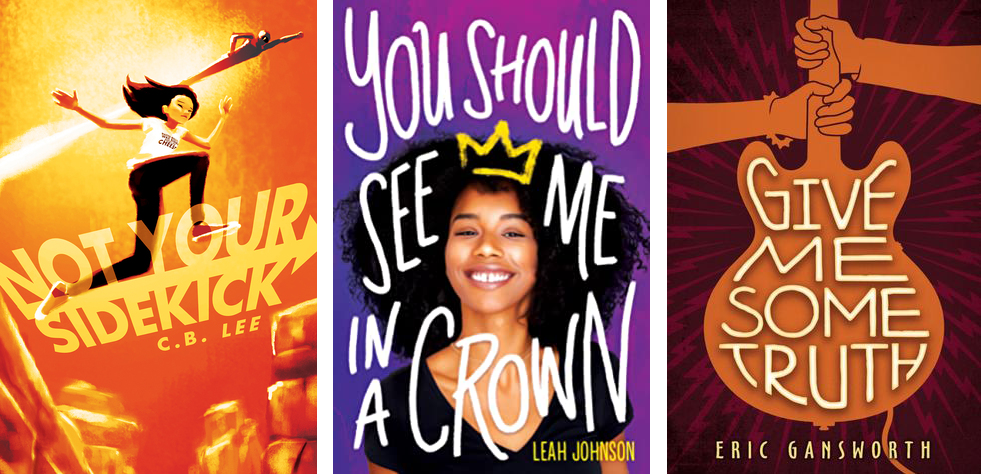

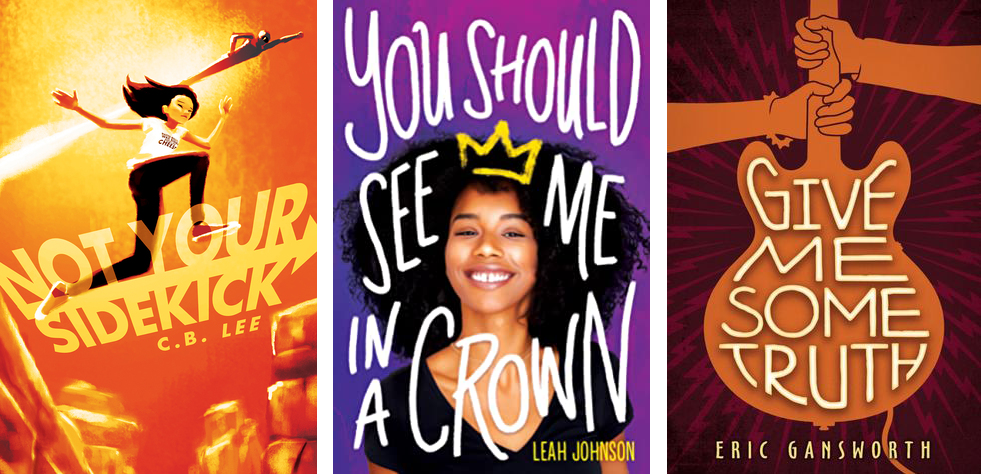

Young adult: Not Your Sidekick by C.B. Lee, You Should See Me in a Crown by Leah Johnson, Give Me Some Truth by Eric Gansworth

Treating Groups as Monoliths

Author Padma Venkatraman doesn’t mind being mistaken for Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri, but she doesn’t think they look alike. “Nor do we all, within a given group, share the same views,” Venkatraman wrote in a 2018 blog post. As Venkatraman wrote, diversifying bookshelves does not mean just checking off one book for each census category: “It means listening to — and learning about — and loving — individual voices, which differ within race, within gender, within every label that can be used to group people.” Middle school teacher and children’s author Lisa Stringfellow said that idea is also important when recommending books to young readers. She cautioned against assuming a student will relate to a book solely based on race or ethnicity. That mistake is played for humor in the graphic novel New Kid by Jerry Craft, in a scene where a librarian pushes a gritty urban novel about a poor, fatherless protagonist on a Black boy. The boy’s father, it turns out, is the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. “Getting to know our students on a personal level is what is needed and not seeing our students’ identities as monoliths,” said Stringfellow.

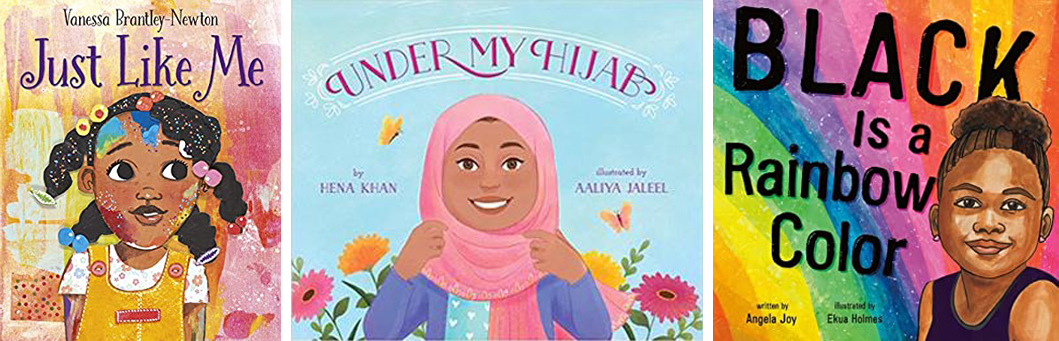

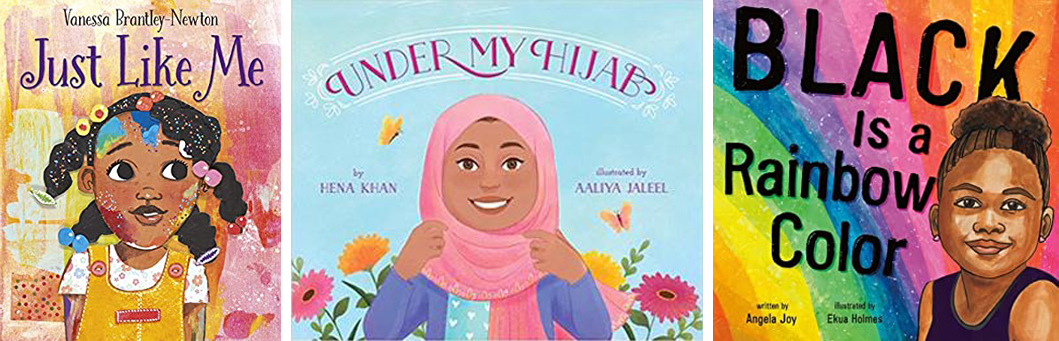

Picture books: Just Like Me by Vanessa Brantley-Newton, Under My Hijab by Hena Khan and illustrated by Aaliya Jaleel, Black Is a Rainbow Color by Angela Joy and illustrated Ekua Holmes

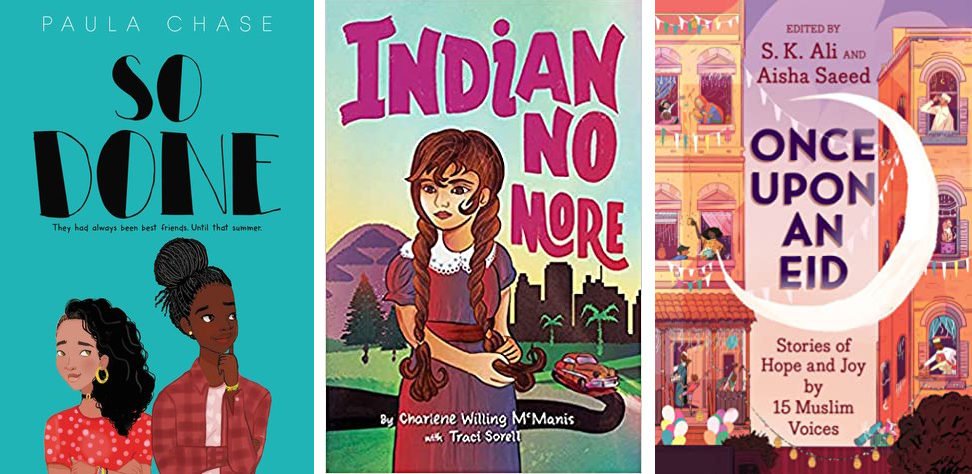

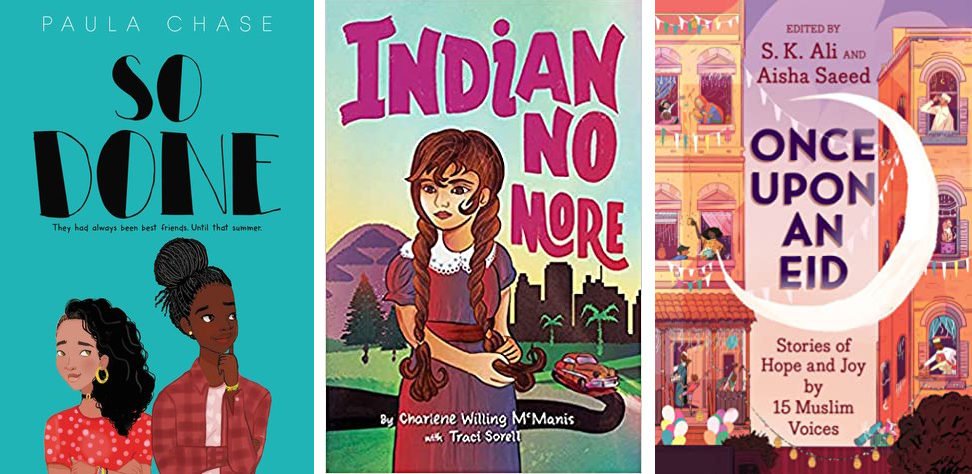

Middle grade: So Done by Paula Chase, Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis with Traci Sorell, Once Upon an Eid edited by S.K. Ali

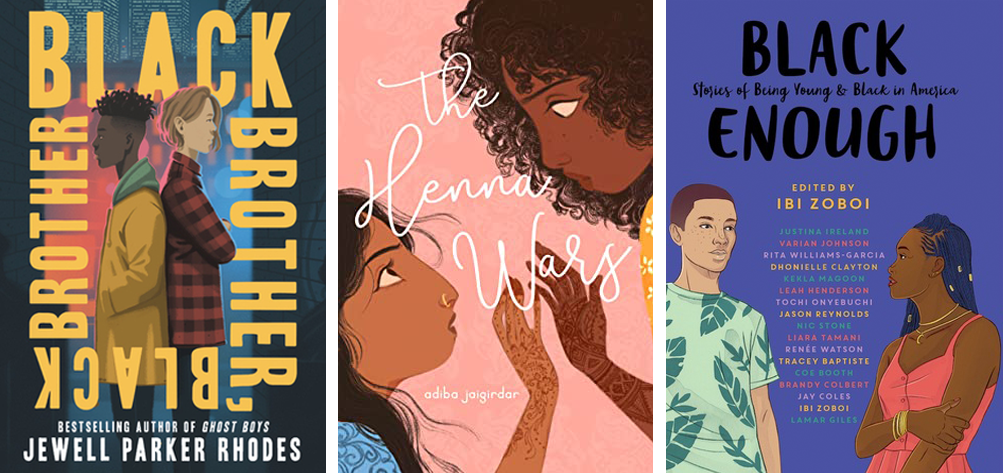

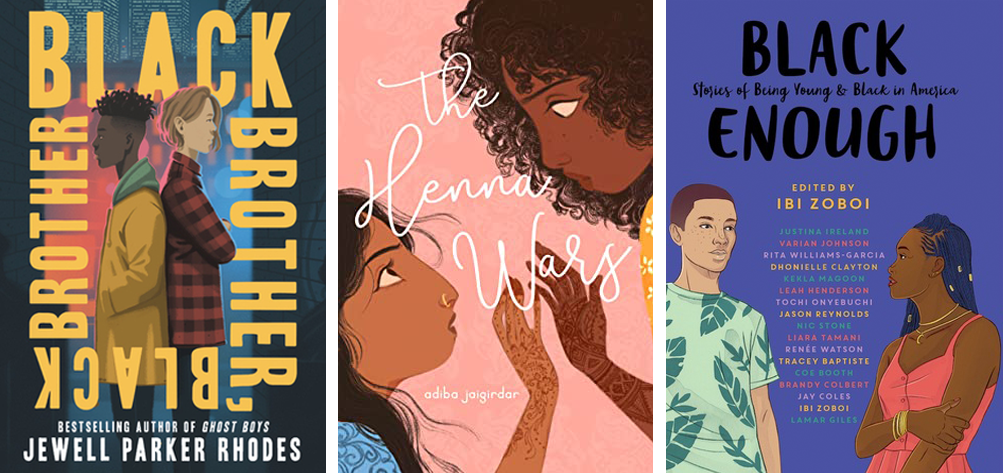

Young adult: Black Brother, Black Brother by Jewell Parker Rhodes, The Henna Wars by Adiba Jaigirdar, Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America edited by Ibi Zoboi

Excluding #OwnVoices

In 2015, amid the growing push for greater diversity in children’s books, Corrine Duvyis, author and cofounder of the Disability in Kidlit website, suggested using the hashtag #OwnVoices “to recommend kidlit about diverse characters written by authors from that same diverse group.” The goal, Duyvis wrote, was “not to discourage people from writing outside their own experiences. It’s to lift up those who are often ignored.” Duyvis’ idea took off in the publishing world, though it has taken longer to reach school librarians. For Stringfellow, own-voices authors bring something to stories that “someone who is outside of that community, no matter how much they’ve researched, would never be able to capture fully.” That authenticity has a powerful effect, especially for students who share that identity, Stringfellow said. When doing class readings of One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia, for example, she stops to chat with students about the characters’ grandmother pressing their hair. Those details might otherwise go unnoticed by her mostly white students, she said, but students of color appreciate the conversation, because questions and comments about hair are a big source of microaggressions in school. Martin said that supporting own-voices authors also signals to those in the publishing industry — who are mostly white, straight, cisgender and non-disabled women — that there’s interest in stories beyond the ones that publishers have typically been willing to back financially.

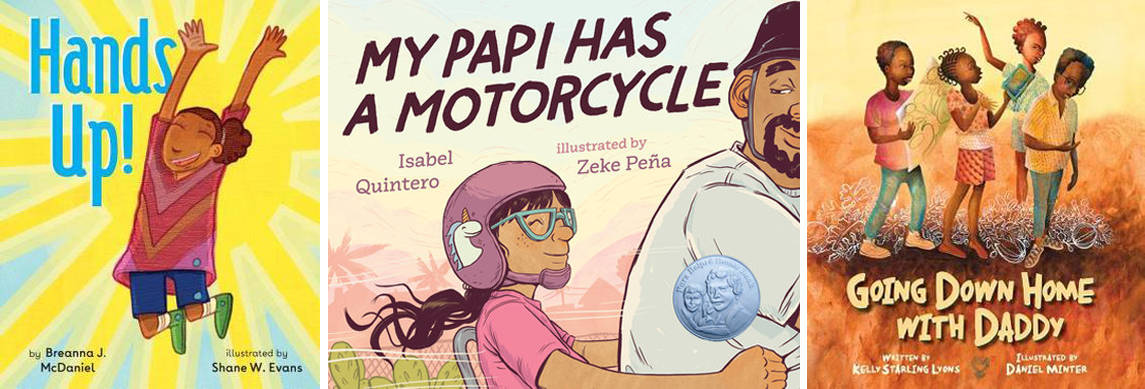

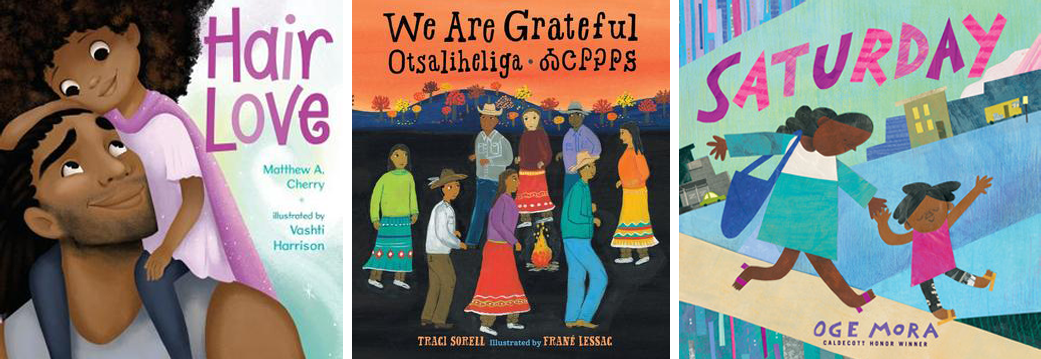

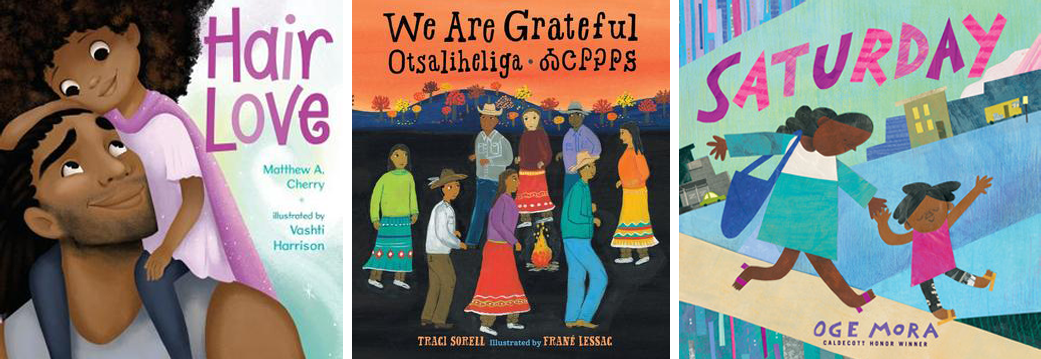

Picture books: Hair Love by Matthew A. Cherry and illustrated by Vashti Harrison, We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga by Traci Sorell and illustrated by Frané Lessac, Saturday by Oge Mora

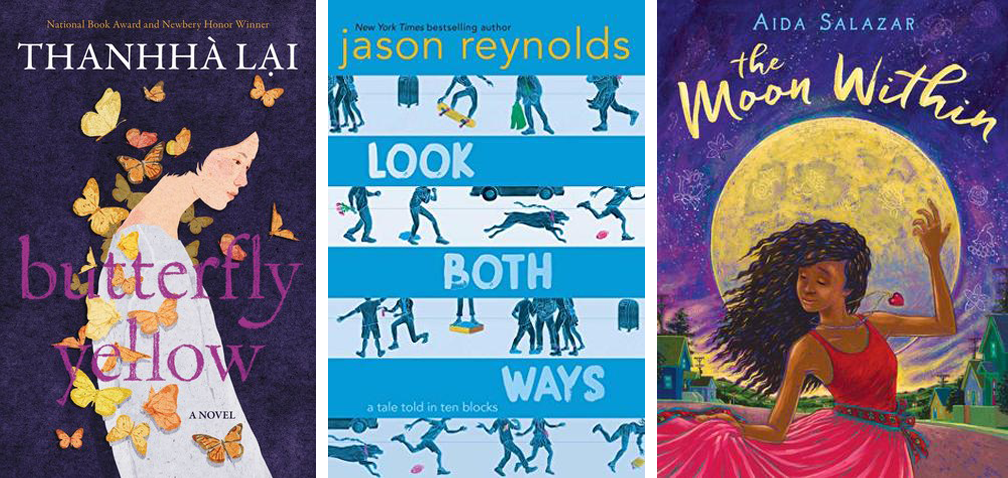

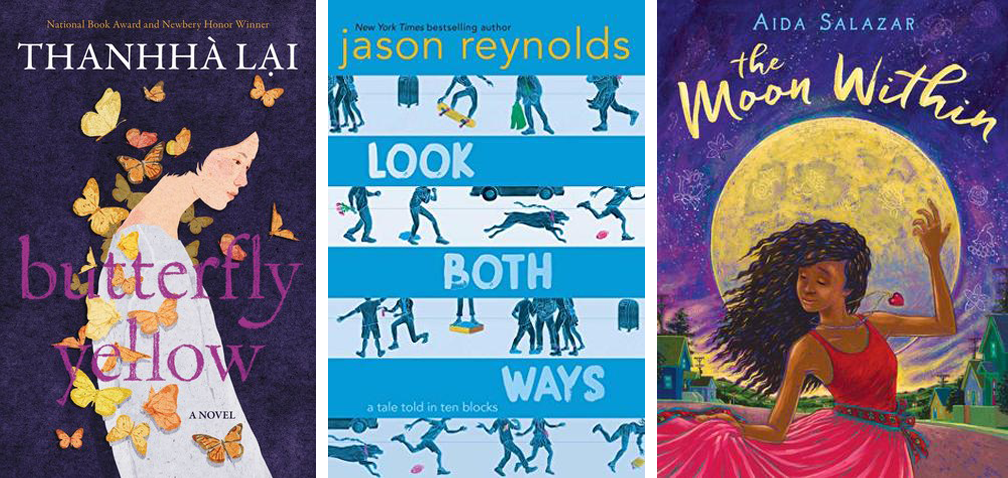

Middle Grade: Butterfly Yellow by Thanhha Lai, Look Both Ways by Jason Reynolds, The Moon Within by Aida Salazar

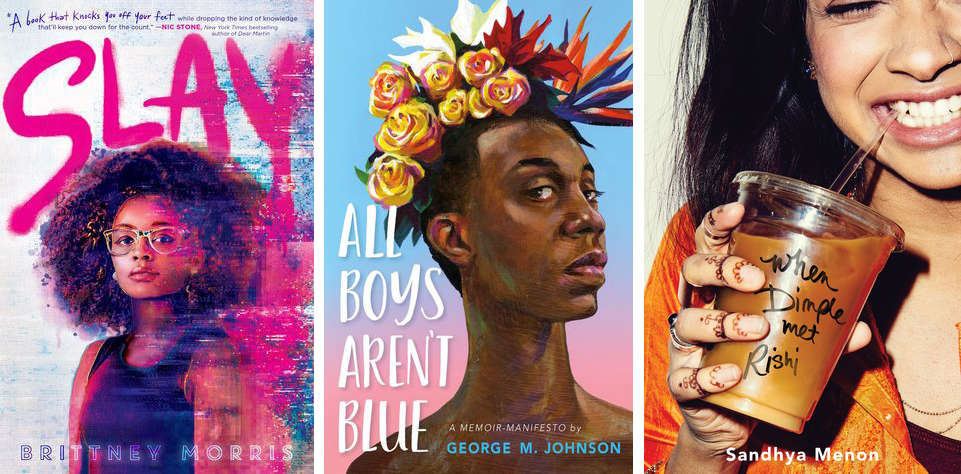

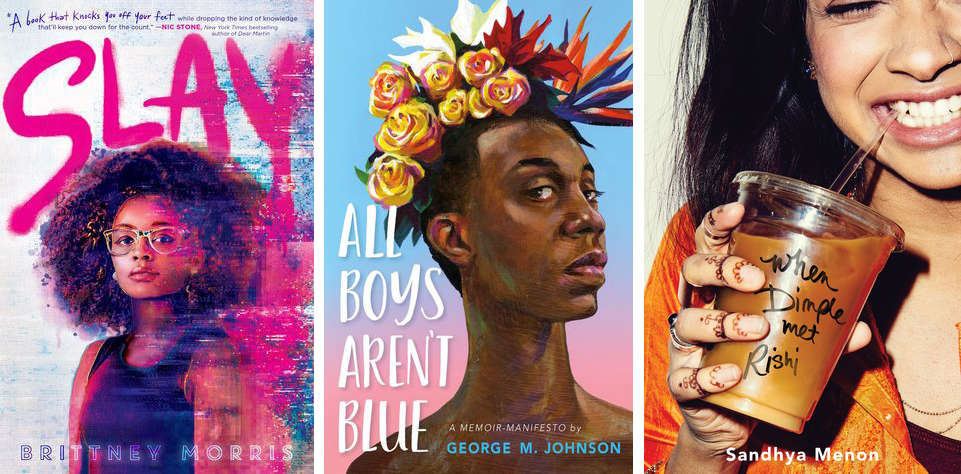

Young Adult: Slay by Brittney Morris, All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, When Dimple Met Rishi by Sandhya Menon

Stopping at the Text