“I was one of [those] kids that learned to read way later,” said Woods. “I was the class clown to avoid being in the situations of reading, being in the situations of math, so I would just act out.”

Similarly, Poor writes about how she had dyslexia and undiagnosed learning disabilities that made school difficult even though she was naturally curious. “I’ve carried that with me. That idea of being told that I wasn’t smart, that I couldn’t do things, that I was bothersome because teachers had to explain things to me over and over again,” she said.

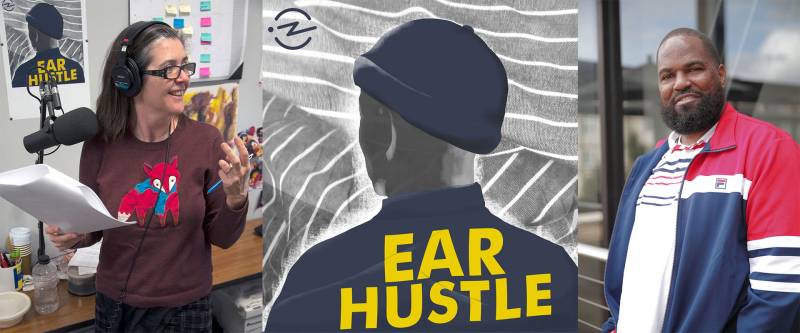

With a podcast that is already rich with activities for young learners, “This is Ear Hustle” provides more accounts from incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people that students can explore in the classroom.

How podcasts build writing skills

Benjamin Bush, a Kentucky-based high school English teacher, started using Ear Hustle in his class because he was looking for a new way to engage his students. “The biggest problem that I think that it addresses is apathy. Getting someone to just start working on something is the hardest,” said Bush.

Ear Hustle drew in his learners because it allowed them to listen to voices other than his. They could hear from a wide range of people featured on the podcast and relate to their experiences. “We got to know the backgrounds of their lives and the things that they had struggled with through poverty and trauma, which affects a lot of our kids,” he said.

After each episode, Bush’s students did a related writing assignment. “It allowed me to reimagine what a text is in a classroom and how multimedia exists in a classroom in the same way that a novel or a play would.” For example, “Cellies” examines the size of a typical prison cell (Woods’ was five feet by ten feet at San Quentin) and how to negotiate the space with a cellmate. “We all have roommates at some point in our lives,” writes Woods in his book. “We also wanted the subject to be something that everybody could relate to—whether they were in prison or in society.” In class, Bush and his students used rulers to measure out the size of a cell and did creative writing about what it would feel like to inhabit the limited space with another person.

For another assignment, Bush brought in additional articles about solitary confinement, sentencing guidelines and parole rules for students to fuel their classroom conversations about prison systems. Later, students could choose to write a persuasive argument piece about one of the issues they talked about.

After listening to “Catch a Kite,” an episode about receiving letters, students had the opportunity to write a letter to someone in the podcast. In one letter, a student talks about how he identifies with how his letter recipient needed to commit crimes to support his family. Another student wrote about how “Thick Glass,” Ear Hustle’s episode about parenting, helped her understand dynamics within her own family. “Her father had been in and out of prison,” Bush said. “She wrote in her letter that Ear Hustle allowed her to envision her father as a good father. She was able to see him as redeemable in a way that maybe she hadn’t before.”

Connection and a sense of not being alone in hard situations are key feelings that Woods hopes to leave with young people who listen to Ear Hustle’s stories. He also thinks these connections help young people become better learners. “You can benefit from someone’s story,” he said. “You can have a different insight on something that will help you navigate through your life.”

Kinetic learning and listening

Ear Hustle co-host Nigel Poor has brought the podcast into her photography classes at California State University, Sacramento, saying its focus on storytelling primes students to slow down and build important skills in observing. “I use it to talk about storytelling and compassionate listening and building empathy, which I think are tools anybody needs no matter what they’re studying.”

For her class, Ear Hustle is the basis of a kinetic learning experience to help students pay attention to other invisible stories. She’ll tell students to go for a walk outside and find something discarded on the ground that draws their attention. Picking up abandoned bits and pieces is part of Poor’s art practice, and when she first started volunteering at San Quentin, she would collect things from the prison’s parking lot. In the book, she describes the lot as her “hunting ground.”

In class, she’ll invite students to bring back their found object and share a story they’ve created about it. “It sounds weird at first, but it gets people to connect with their creativity and the associations that they make with objects and experiences. And that’s, to me, where stories start.” She’ll then move into playing clips from Ear Hustle and discussing what people hear in them and how she and Earlonne put episodes together.

“There’s so much [emphasis] put on the end result,” said Poor about education. “Listening and thinking is actually a valid activity. So I like to talk about that, and I like to talk about ways to pull stories out of people and give people the confidence to talk about themselves.”

Using hands-on learning to understand systems

Danielle Devencenzi, assistant principal at St. Ignatius College Prep high school in San Francisco, begins her criminal justice class by looking at major legislation that shaped the U.S. justice system such as California’s Three Strikes Sentencing Law, the 1994 Crime Bill and landmark US Supreme Court cases. “Twelve years ago, I started to take my students to San Quentin to really understand the social justice issues facing our prison system in California, specifically mass incarceration,” she said.