“They can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel,” said Franciene Sabens, a counselor who’s noticed the ninth and 10th graders at her southern Illinois high school are struggling more than older students this year. “They’re trying to find their groove, and they haven’t had real, normal school in two years.”

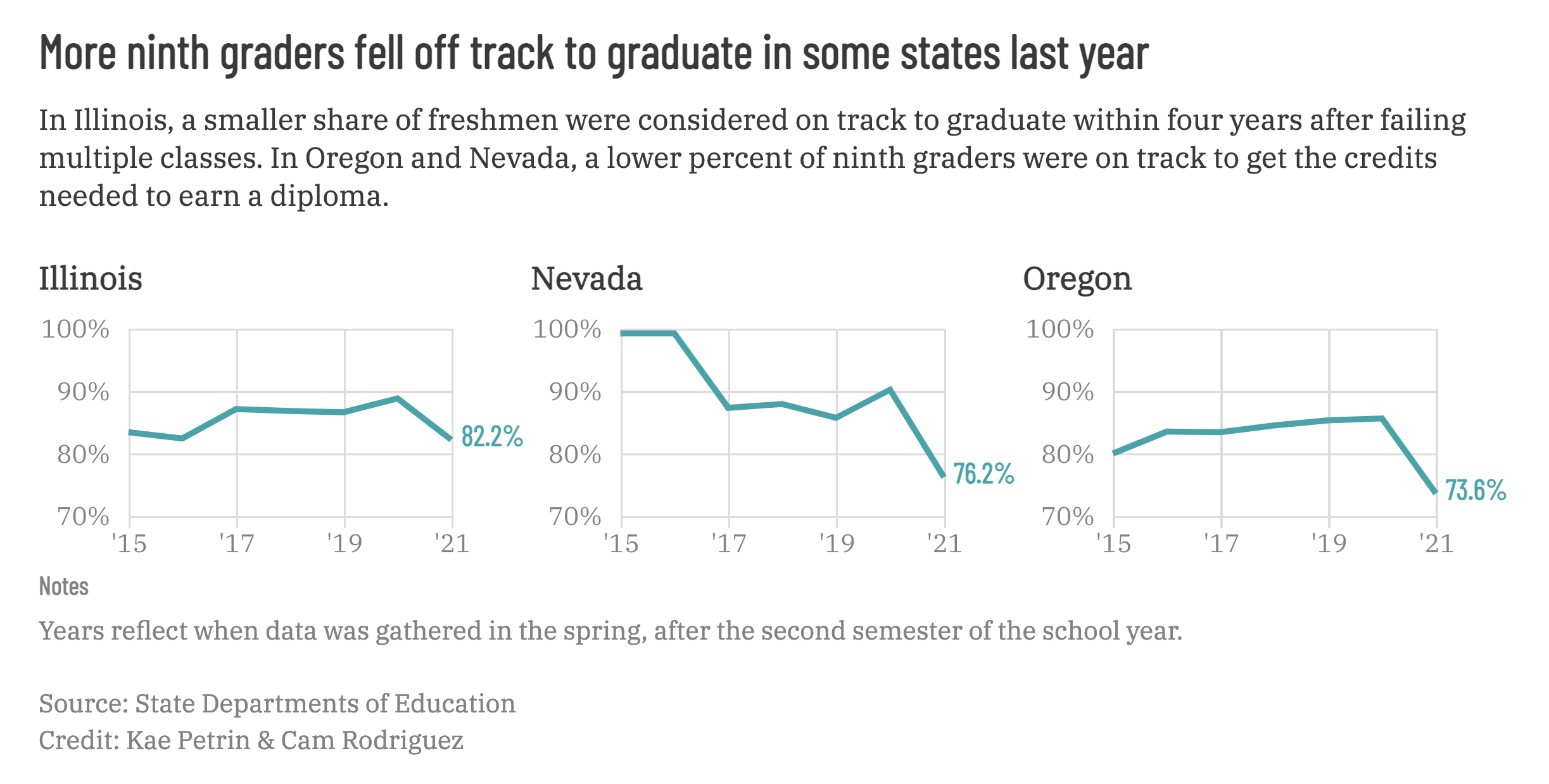

Many ninth graders had an especially rocky transition to high school last school year without the support of in-person classes and after-school activities. Some fell behind in their virtual classes or while they were in quarantine, and are now struggling to make up missed credits. Others got overwhelmed as they tried to balance school with caring for younger siblings or other responsibilities.

Now, schools are trying to help younger high schoolers get back on track, from hiring staff specifically to work with struggling students to rethinking how students can make up failed classes. Some schools are getting more hands-on with advising or making small tweaks to get students the help they need during the school day.

Like many high schools, Oregon’s South Salem High School typically offered students who’d failed a class the chance to retake it in person or to make it up online with a credit recovery program.

But after many students saw their grades plummet during remote learning, the school looked for another option. This fall, the school offered make-up English, history, math, and science classes for 10th graders that were more tailored to students’ individual needs. The students worked with a teacher to figure out exactly which standards they’d failed, and came up with a plan to make up only those missing assignments.

“It has been incredibly successful,” said counselor Ben Handrich. “A lot of our ninth graders were not engaging with distance learning, and they just started flying through” these shorter make-up plans.

In Chicago, where researchers helped pioneer the use of freshmen on-track indicators, coaches at the Network for College Success, which works with 18 high schools in the city, have been helping teachers make small changes to support ninth graders.

A key question they’ve been focusing on is: “As a teacher, what’s in my locus of control to change?” said Sarah Howard, who oversees the group’s coaching work.

That could look like surveying students about what worked, and what didn’t, after a lesson. It could also mean anticipating times in the school calendar where student motivation slumps — like when the weather is cold or there’s a long stretch without a holiday — and keeping that in mind when assigning work and setting deadlines.

“I can think about, what’s the rhythm in my classroom that gives kids more space, more room, more flexibility,” Howard said.

At Elverado High School in Illinois, Sabens has found that many of the younger high schoolers who’ve failed classes struggled to break their homework assignments up into manageable chunks. Recently, Sabens sat down with the school’s science teacher and came up with a plan to help those students work on their organizational skills.

Sabens took home the ninth grade science book and typed up the text’s vocabulary words and unit questions so students knew exactly what their teacher wanted them to answer. The teacher also tried setting more mini-deadlines for students and offered more class time to finish homework.

But Sabens still worries about a group of freshmen who failed science earlier this year, which she likens to “building a house with a cracked foundation.” Often, she says, a student might think: “What’s the big deal? I’ll just make it up.” But that can lead high schoolers “to the point where the outs run out.”

“I want to see them walk across the stage in four years with their friends,” Sabens said. “But their habits are a little bit difficult to break.”

Matt Barnum contributed reporting.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.