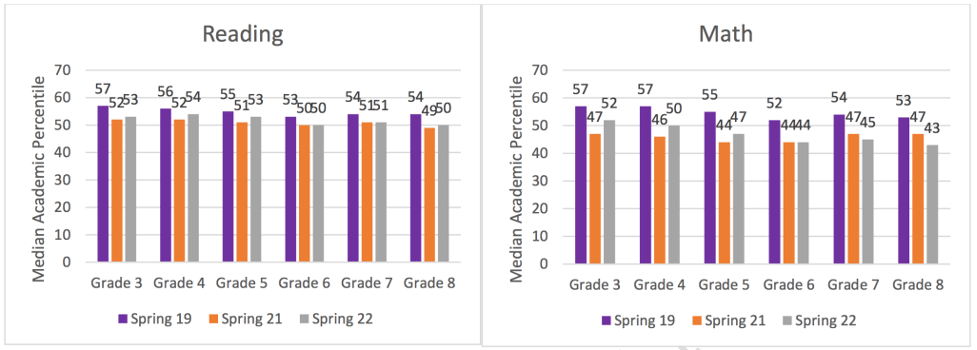

What do we know about how kids are catching up at school as the pandemic drags on? The good news, according to the latest achievement data, is that learning resumed at a more typical pace during the 2021-22 school year that just ended. Despite the Delta and Omicron waves that sent many students and teachers into quarantine and disrupted school, children’s math and reading abilities generally improved as much as they had in years before the pandemic.

“The big picture takeaway is that learning mirrors pre-pandemic trends,” said Karyn Lewis, a researcher at NWEA, which sells assessments to schools to track student progress. Lewis analyzed how student achievement improved between fall and spring assessments, called Measures of Academic Progress or MAP, taken by eight million elementary and middle school children across the country. “In some cases, the growth is a little bit more than a typical year, maybe a 6 percent increase. It’s very small.”

Because of these small increases in the rate of learning, some students were able to make up as much as a quarter or a third of the so-called learning loss that they suffered during the school closures and remote instruction of 2020 and 2021. But even with those gains, student achievement still lags far behind what children at each grade level used to demonstrate before the pandemic.

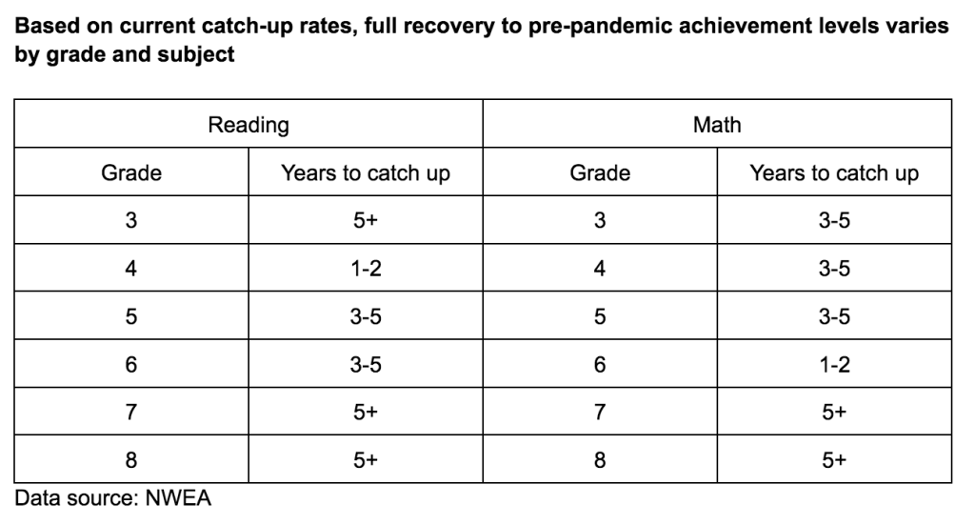

“If improvements continue at the rate we saw this year, the timeline for a full recovery is years away and will likely extend past the availability of federal recovery funds,” NWEA wrote in a press release accompanying a learning loss report released on July 19, 2022. Depending upon the student’s grade and subject, NWEA estimated recovery to be as short as one or two years but surpassing five years in some cases.

Slow recovery: Reading and math scores stabilize and begin to recover for many students. Math scores continue to drop for middle schoolers

A good analogy is a cross-country road trip. Imagine that students were traveling at 55 miles an hour, ran out of gas and started walking instead. Now they’re back in their cars and humming along at 55 miles an hour again. Some are traveling at 60 miles an hour, but they’re still far away from the destination they would have arrived at if they hadn’t run out of gas. It’s this distance from the destination that educators are describing when they talk about learning loss.