Excerpted from “Long Days, Short Years: A Cultural History of Modern Parenting” by Andrew Bomback, © 2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

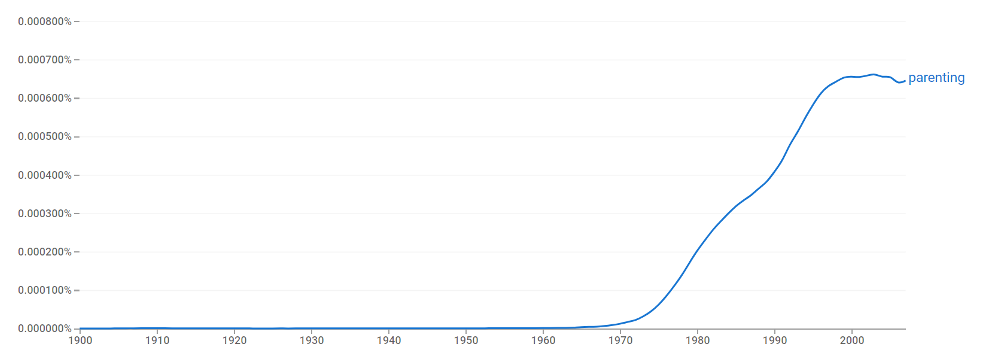

Over just a few decades, parents have increased the amount of time, attention, and money applied to raising children. A mother today who works outside the home spends a similar amount of time and considerably more money (inflation-adjusted) tending her children than a stay-at-home mom did in the 1970s. The usage graphs for the verb form of “parent” on Google Books Ngram Viewer could stand in for similar plots depicting hours per day or dollars per child spent by parents over the last five decades.

The verb form of “parent”—in particular, its gerund “parenting”—was first employed in the United States in the late 1950s according to The Merriam-Webster Dictionary. However, Fitzhugh Dodson’s 1970 book, “How to Parent,” is credited with introducing the verb to a wide audience, defined as “to use with tender loving care all the information science has accumulated about child psychology in order to raise happy and intelligent human beings.” The book became an international best seller and, in turn, irrevocably transformed parenthood from someone to be into something to do. Modern parents, who’ve had fifty years since the book’s publication to absorb the aforementioned “endless, anxious journey of guilt,” would likely be shocked reading “How to Parent” today. Dodson repeatedly advocates spanking and compares disciplining children to training and domesticating animals. These harsh precepts were advanced during a time, as Jennifer Senior points out in “All Joy and No Fun,” when “women were yanking off their aprons, taking the Pill, and fighting for the Equal Rights Amendment.”

The verb form of “parent” entered common usage not because of Dodson’s particular parenting advice but because his book and verb promised empowerment, particularly to women who were leaving home for the workforce in increasing numbers. Raising children was now repurposed as a skill or science that could be learned, practiced, and eventually mastered. This transformation wasn’t limited solely to working mothers either. Around this time, the nomenclature for non-working mothers shifted from “housewife” to “stay-at-home mom.” Senior elucidates why this not-so-minor change in title reflected an overall new cultural emphasis: “The pressures on women [had] gone from keeping an immaculate house to being an irreproachable mom.”

Pressure, as Senior uses the word, is a euphemism for anxiety, which has been a driving force behind shifts in American parenting styles since the country’s inception. A theme emerges when exploring parental anxieties from generation to generation: parents have always focused their concerns on what they can try to control rather than what they know they cannot. Indeed, the awareness that so many crucial factors in a child’s development are beyond a parent’s control often fuels a parent’s anxiety about what is seemingly controllable. This is one area I can make a difference, so I better not mess it up. If we view the seventeenth-century Pilgrims and Puritans as the earliest American parents (recognizing, of course, the thousands of Indigenous parents already here at the time), we already see the pattern in place. The Puritans should have feared infection, the most likely cause of death for everyone in the family, but instead aimed their parenting efforts at rooting out corruption and sin in their children.

Andrew Bomback

Andrew Bomback