Throughout 2022, the Biden administration urged schools to spend their $122 billion in federal recovery funds on tutoring to help students catch up from pandemic learning losses. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said students who had fallen behind should receive at least 90 minutes of tutoring a week. Last summer, the White House put even more muscle behind the rhetoric and launched a “National Partnership for Student Success” with the goal of providing students with 250,000 more tutors over three years.

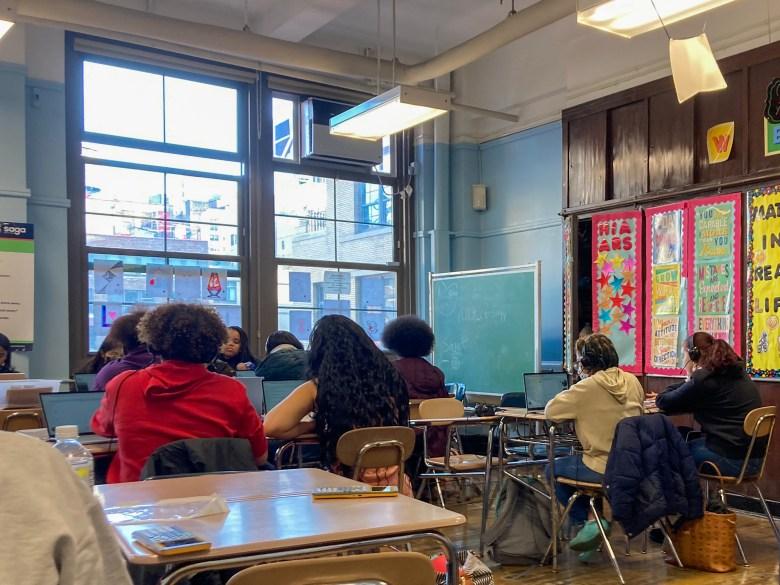

This federal tutoring campaign is based on some of the best evidence that education researchers have ever found for helping students who are behind grade level. What researchers have in mind, however, is not what many people might imagine. Studies have found that sessions once or twice a week haven’t boosted achievement much, nor has frequent after-school homework help. Instead, tutoring produces outsized gains in reading and math – making up for five months of learning in a year by one estimate – when it takes place daily, using paid, well-trained tutors who are following a good curriculum or lesson plans that are linked to what the student is learning in class. Effective tutoring sessions are scheduled during the school day, when attendance is mandatory, not after school.

Think of it as the difference between outpatient visits and intensive care at a hospital. So called “high-dosage tutoring” is more like the latter. It’s expensive to hire and train tutors and this type of tutoring can cost schools $4,000 or more per student annually. (Surprisingly, the tutoring doesn’t have to be one-to-one; researchers have found that well-designed tutoring programs can be very effective when tutors work with pairs of students or in very small groups of three.)

But little is known about how many schools have actually taken up the tutoring cause. And among those who have, it’s unclear exactly what kinds of tutoring programs they have launched and which students are being tutored. The Department of Education provided some answers last week with the release of a national survey conducted in December 2022 of 1,000 schools, from elementary to high school. This School Pulse Panel is far from an ideal survey; the slightly more than 1,000 respondents represent fewer than half of the 2,400 schools that federal authorities surveyed, and some of the responses are inconsistent and confusing. But it’s the best snapshot of the recovery that we have so far.

More than four out of five schools said they were offering at least one version of tutoring this 2022-23 school year, ranging from traditional after-school homework help to intensive tutoring. But the modes varied: 37 percent said they were giving students high-dosage tutoring; 59 percent said they were administering standard tutoring; 22 percent said they were offering self–paced tutoring, and 5 percent said they were doing other types of tutoring. The numbers exceed 100 percent because some schools are offering several types of tutoring at the same time, administering different kinds to different students in different subjects. (For more details on how each mode of tutoring was defined, here is that question in the survey.)