“From my perspective you could find and replace ‘DCPS’ [DC Public Schools] for basically any major school system right now,” tweeted Ben Speicher, the principal of a charter school in Philadelphia. “The shift in post-HS [high school] plans is a real uncovered story right now.”

Morgan Polikoff, an associate professor of education at the University of Southern California, is collecting reports from around the country to summarize what is happening in schools beyond the well-documented nationwide slide in test scores. “My general perception is basically that the trends in D.C. are true everywhere—attendance is way down, grades are up, high school graduation is slightly up, college enrollment is down,” said Polikoff in an email.

The Washington report described how school leaders are still struggling to persuade students to come to school regularly in the 2022-23 school year, despite such incentives as student awards and celebrations and efforts to contact parents. The report also connected the dots between poor attendance and low test scores. Students who were designated as “at-risk” because they were homeless, in foster care or their families were poor enough to receive social welfare benefits, had the lowest academic outcomes, reflecting that these groups of students had the highest rates of chronic absenteeism in the previous school year. Only 15% of “at-risk” students met grade-level expectations in reading. In math, only 6% did.

A majority of D.C. public school students are Black. But just 9% of the city’s Black high school seniors were deemed to be college or career ready in 2021-22, according to an SAT benchmark, a three percentage point decline from before the pandemic.

A majority of D.C. public school students are Black. But just 9% of the city’s Black high school seniors were deemed to be college or career ready in 2021-22, according to an SAT benchmark, a three percentage point decline from before the pandemic.

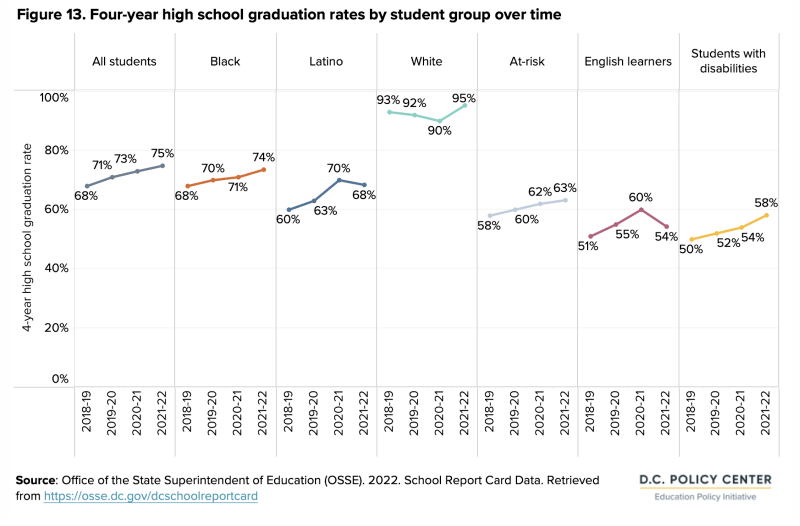

More research is needed to understand why so many schools are giving high grades to students who haven’t mastered material and graduating so many ill-prepared students. In some cases, schools have eased graduation requirements. Washington suspended a requirement for high school students to perform 100 hours of community service, but students were supposed to be in school for a minimum number of instructional hours again in 2021-22. It’s puzzling how high school graduation rates increased, given that absenteeism was so high.

As I cover pandemic fallout, I am constantly struck by the grim academic toll and how oblivious so many families are to their children’s predicament. National assessments tell us that 20 years of academic progress were erased in a year. Middle school students are terribly behind in math. Third graders are so behind grade level in reading that the curriculum and assessment company Amplify warns that a third are in need of intensive remediation. Yet, there are multiple reports that parents aren’t signing their children up for free tutoring, even when schools make it available. Who can blame them when their children’s grades are strong and their children are on track to graduate?

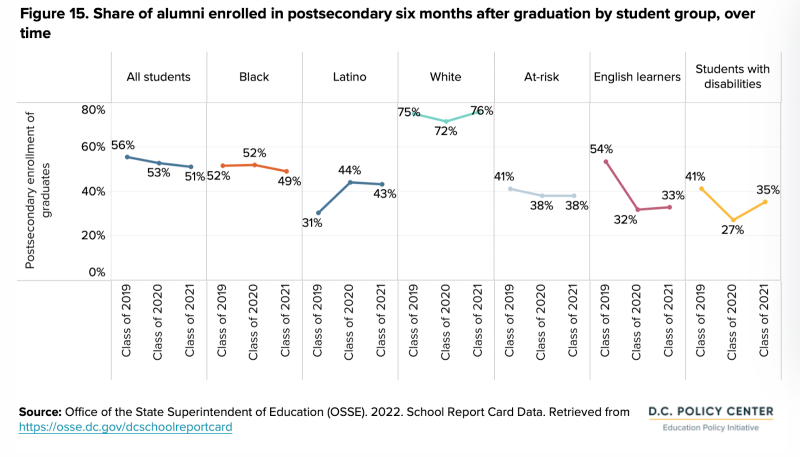

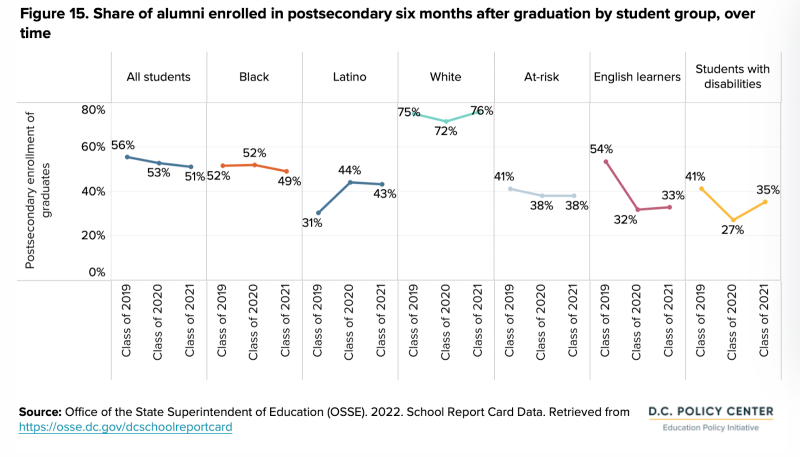

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center has been documenting the collapse in college-going since the pandemic started, particularly at community colleges. I’ve been focused on the economic reasons. With such a strong labor market, many teens can get a job with decent hourly wages and help support their families. I hadn’t considered how so many more high school graduates might be too ill-prepared for college or a job training program even if they enrolled in one.

Years from now, we could have too many young adults without the skills to get a good job. And companies won’t have skilled people to hire. That will hobble the economy for everyone.

This story about a pandemic fallout report in Washington D.C. was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.

Based on these trends, the D.C. Policy Center predicted that only eight students out of every 100 ninth graders in the district would earn a post-secondary credential within six years of high school graduation. Before the pandemic, 14 out of every 100 ninth graders were predicted to hit that important milestone.

Based on these trends, the D.C. Policy Center predicted that only eight students out of every 100 ninth graders in the district would earn a post-secondary credential within six years of high school graduation. Before the pandemic, 14 out of every 100 ninth graders were predicted to hit that important milestone.

A majority of D.C. public school students are Black. But just 9% of the city’s Black high school seniors were deemed to be college or career ready in 2021-22, according to an SAT benchmark, a three percentage point decline from before the pandemic.

A majority of D.C. public school students are Black. But just 9% of the city’s Black high school seniors were deemed to be college or career ready in 2021-22, according to an SAT benchmark, a three percentage point decline from before the pandemic.