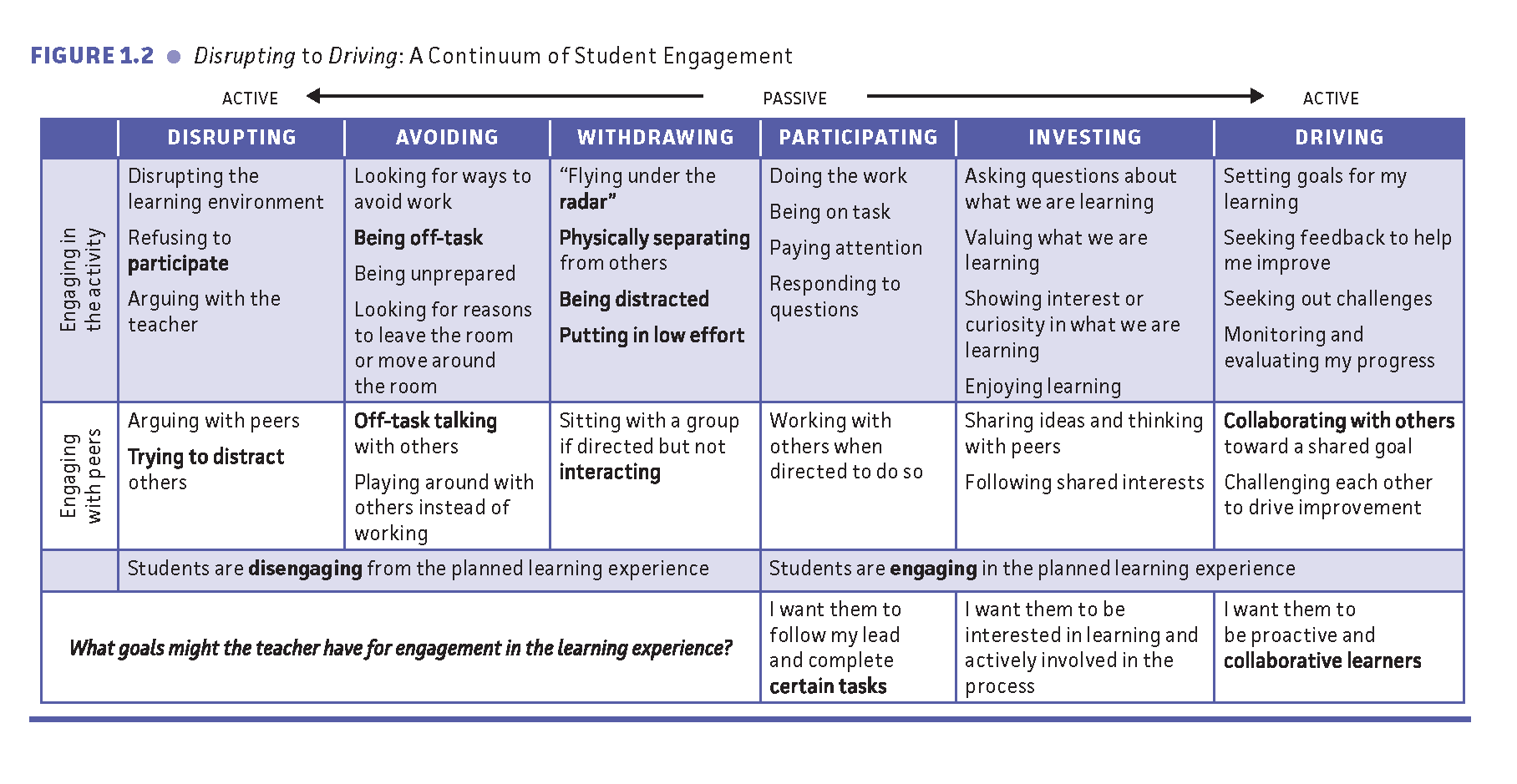

This form of engagement is characterized by students’ compliant behavior and willingness to do what the teacher has asked them to do. Behaviors associated with this type of engagement include being on task, being focused, paying attention, doing work, and responding to teacher questions. In relation to engaging with peers, this is limited to working in groups or pairs when directed to do so by the teacher. When expectations for engagement sit at this level, the focus is on listening to the teacher, following the teacher’s instructions, and completing the tasks that have been assigned by the teacher.

Investing

“Students who are engaged ask a lot of questions, are keen and curious, want to know more, and think actively about what they are working on.”

When students move from passive compliance to this more active form of engagement, we see signs that they are personally invested in and finding value in what they are learning. Behaviors include showing curiosity and interest, displaying signs they are enjoying learning, asking questions about what they are learning, engaging in discussions about the learning, and thinking more deeply about what they are learning. This includes wanting to share their questions, ideas, and experiences with peers during the learning experience, either as part of a whole-class discussion or during small-group activities. When expectations for engagement sit at this level, the focus is on deeper thinking, more active involvement in learning, and students feeling that what they are learning is both interesting and meaningful.

Driving

“That was important to them. That was the focus that was driving them, and every thought they had was what they wanted to do. They kept asking, ‘When are we having time to plan?’”

In this most active form of engagement, students are striving toward a goal they have set for themselves, one that is personally meaningful to them and involves a certain level of challenge. We sometimes refer to this kind of challenge as “hard fun.” Behaviors associated with driving include setting goals for learning; engaging in self-reflection, self-assessment, and self-evaluation; seeking feedback to help them improve; and looking for ways to extend their learning. At this level, engagement with peers is also at its highest level. This can include actively collaborating with others to learn together and actively seeking out peers as a valuable source of feedback and support during learning. When expectations for engagement are at this level, the focus is on wanting students to successfully “drive” their own learning, either individually or collaboratively, and make use of available resources (including peers) to support improvements in learning.

When students are driving, they are becoming masters of their own learning and engaging in behaviors characteristic of self-regulated learning. This includes setting goals for improving, making a plan for improvement, taking actions and using strategies to achieve that goal, monitoring and evaluating progress toward the goal, and using feedback to guide improvement.

Three forms describe students disengaging from the planned learning activity; they range from passive withdrawal through actively attempting to disrupt the learning environment.

Withdrawing

“They’ve just pulled the blinds down; you can see them automatically glaze over, and it doesn’t matter what you’re saying — you’ve lost them.”

Students who are passively disengaged in the learning experience are often described as “flying under the radar.” They are not trying to call attention to themselves or cause any disruption, but they are also not participating in the planned learning experience. Behaviors that are associated with this form of disengagement include appearing distracted, not making eye contact, daydreaming, physically withdrawing from the group, staring out the window, and lacking participation or effort. In this passive form of disengaging from the learning experience, students are only engaging with peers when directed to do so by the teacher. This may involve sitting with a group as part of a group activity but not interacting with others during the activity.

Some students actively engage in not being visible to the teacher, hoping never to be asked questions in class, and seeming like they are there but not. While this may seem like a harmless form of disengaging, the impact of passive disengagement on learning is just as serious as the more active forms of disengaging.

Avoiding

“They find excuses to go out of the room a lot, or go to their bag a lot. They sit on the computer and find other things to do instead of staying on task.”

Students at this level of disengagement are often described as being off task and actively looking to avoid engaging in the planned learning experience. Unlike the withdrawing form, students are not as concerned with going unnoticed, and they are actively seeking out other things to do rather than passively disengaging. Behaviors associated with this form of disengagement include moving around the room unnecessarily, being off task, asking to leave the room, and being unprepared. In relation to engaging with peers, students may engage in off-task behavior like talking or playing with materials with other students who are also looking to avoid engaging in the planned learning activity.

Disrupting

“They go around to someone else’s desk and start an argument about something — goofing around, being loud, and causing a bit of trouble.”

In this form of disengagement, students are actively disrupting the learning environment or explicitly refusing to participate in the planned learning experience. Behaviors include arguing with the teacher or peers, being noncompliant, trying to distract others, and moving around the room in a way that causes a disruption to learning (e.g., running around, rolling around on chairs). In relation to engaging with peers, students at this level might get into arguments with peers or try to distract them by attempting to attract their attention away from the planned learning activity. They can be actively engaged in being disruptive, and reprimands can reinforce these behaviors by showing the disruptive students and their peers how successful they can be in their disrupting role.

This continuum offers an additional vantage point from which we can think about student engagement, this time from the perspective of the teacher, and an expanded vocabulary for discussing engagement within the context of classroom learning.

Disrupting to Driving: A Continuum of Student Engagement

Disrupting to Driving: A Continuum of Student Engagement

Amy Berry has over 20 years of experience working in education as a teacher, researcher and professional learning facilitator. She is a Research Fellow with the Australian Council for Educational Research and an Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Amy was a teacher in Queensland, Australia for 10 years before returning to university to pursue her interest in education research and teacher professional learning. She has extensive experience working with pre-service and practicing teachers to develop their skills and improve their practice. She has designed and facilitated numerous professional learning programs for teachers, including programs on formative assessment, student engagement, and learning through play. As well as working with teachers in Australia, Amy has worked with teachers, school leaders, and education officials from the U.S,, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and Ukraine. She is passionate about helping learners of all ages find their joy in learning.

Amy Berry has over 20 years of experience working in education as a teacher, researcher and professional learning facilitator. She is a Research Fellow with the Australian Council for Educational Research and an Honorary Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Amy was a teacher in Queensland, Australia for 10 years before returning to university to pursue her interest in education research and teacher professional learning. She has extensive experience working with pre-service and practicing teachers to develop their skills and improve their practice. She has designed and facilitated numerous professional learning programs for teachers, including programs on formative assessment, student engagement, and learning through play. As well as working with teachers in Australia, Amy has worked with teachers, school leaders, and education officials from the U.S,, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and Ukraine. She is passionate about helping learners of all ages find their joy in learning.