If we graded schools on how accurately they grade students, they’d fail. Nearly six out of 10 course grades are inaccurate, according to a new study of grades that teachers gave to 22,000 middle and high school students in 2022 and 2023.

The Equitable Grading Project, a nonprofit organization that seeks to change grading practices, compared 33,000 course grades with students’ scores on standardized exams, including Advanced Placement tests and annual state assessments. The organization considered a course grade to be inaccurate if a student’s test score indicated a level of knowledge that was at least a letter grade off from what the teacher had issued. For example, a grade was classified as inaccurate if a student’s test score indicated a C-level of skills and knowledge, but the student received an A or a B in the course. In this example, a D or an F grade would also be inaccurate.

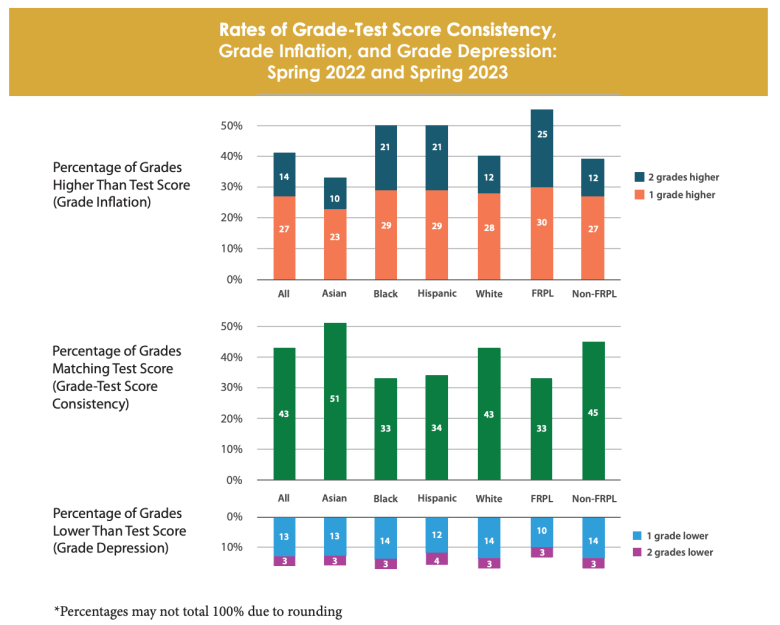

Inflated grades were more common than depressed grades. In this analysis, over 40% of the 33,000 grades analyzed – more than 13,000 transcript grades – were higher than they should have been, while only 16% or 5,300 grades were lower than they should have been. In other words, two out of five transcript grades indicated that students were more competent in the course than they actually were, while nearly one out of six grades was lower than the student’s true understanding of the course content.

The discrepancy matters, the white paper says, because inaccurate grades make it harder to figure out which students are prepared for advanced coursework or ready for college. With inflated grades, students can be promoted to difficult courses without the foundation or extra help they need to succeed. Depressed grades can discourage a student from pursuing a subject or prompt them to drop out of school altogether.

“This data suggests that hundreds, perhaps thousands, of students in this study may have been denied, or not even offered, opportunities that they were prepared and eligible for,” the white paper said.