The fact that students with dual enrollment credits are faring better than students without dual enrollment credits isn’t terribly persuasive. In order to qualify for the classes, students usually need to have done well on a test, earned high grades or be on an advanced or honors track in school. These high-achieving students would likely have graduated college in much higher numbers without any dual enrollment courses.

“Are we subsidizing students who were always going to go to college anyway?” asked Kristen Hengtgen, a policy analyst at EdTrust, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization that lobbies for racial and economic equity in education. “Could we have spent the time and energy and effort differently on higher quality teachers or something else? I think that’s a really important question.”

Hengtgen was not involved in this latest analysis, but she is concerned about the severe underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic students that the report highlights. A data dashboard accompanying the new report documents that only 9 percent of the high schoolers in dual enrollment classes were Black, while Black students made up 16 percent of high school students. Only 17 percent of dual enrollment students were Hispanic at a time when Hispanic students made up almost a quarter of the high school population. White students, by contrast, took 65 percent of the dual enrollment seats but represented only half of the high school population. Asian students were the only group whose participation in dual enrollment matched their share of the student population: 5 percent of each.

Advocates of dual enrollment have made the argument that an early taste of college can motivate students to go to college, and the fact that so few Black and Hispanic students are enrolling is perhaps is the most troubling sign that the giant public-and-private investment in education isn’t fulfilling one of its main objectives: to expand the college-educated workforce.

Hengtgen of EdTrust argues that Black, Hispanic and low-income students of all races need better high school advising to help them sign up for the classes. Sometimes, she said, students don’t know they have to have a prerequisite class in 10th grade in order to be eligible for a dual enrollment class in 11th grade, and by the time they find out, it’s too late. Cost is another barrier. Depending upon the state and county, a family may have to pay fees to take the classes. Though these fees are generally much cheaper than what college students pay per course, low-income families may still not be able to afford them.

Tatiana Velasco, an economist at CCRC and lead author of the October 2024 dual enrollment report, makes the argument that dual enrollment may be most beneficial to Black and Hispanic students and low-income students of all races and ethnicities. In her data analysis, she noted that dual enrollment credits were only providing a modest boost to students overall, but very large boosts to some demographic groups.

Among all high school students who enrolled in college straight after high school, 36 percent of those with dual enrollment credits earned a bachelor’s degree within four years compared with 34 percent without any dual enrollment credits. Arguably, dual enrollment credits are not making a huge difference in time to completion, on average.

However, Velasco found much larger benefits from dual enrollment when she sliced the data by race and income. Among only Black students who enrolled in college straight away, 29 percent of those who had earned dual enrollment credits completed a bachelor’s degree within four years, compared to only 18 percent of those without dual enrollment credits. That’s more than a 50 percent increase in college attainment. “The difference is massive,” said Velasco.

Among Hispanic students who went straight to college, 25 percent of those with dual enrollment credits earned a bachelor’s degree within four years. Only 19 percent of Hispanic college students without dual enrollment credits did. Dual enrollment also seemed particularly helpful for college students from low-income neighborhoods; 28 percent of them earned a bachelor’s degree within four years compared with only 20 percent without dual enrollment.

Again, it’s still unclear if dual enrollment is driving these differences. It could be that Black students who opt to take dual enrollment classes were already more motivated and higher achieving and still would have graduated college in much higher numbers. (Notably, Black students with dual enrollment credits were more likely to attend selective four-year institutions.)

There is a wide variation across the nation in how dual enrollment operates in high schools. In most cases, high schoolers never step foot on a college campus. Often the class is taught in a high school classroom by a high school teacher. Sometimes community colleges supply the instructors. English composition and college algebra are popular offerings. The courses are generally designed and the credits awarded by a local community college, though 30 percent of dual enrollment credits are awarded by four-year institutions.

A few other takeaways from the CCRC and National Student Clearinghouse report:

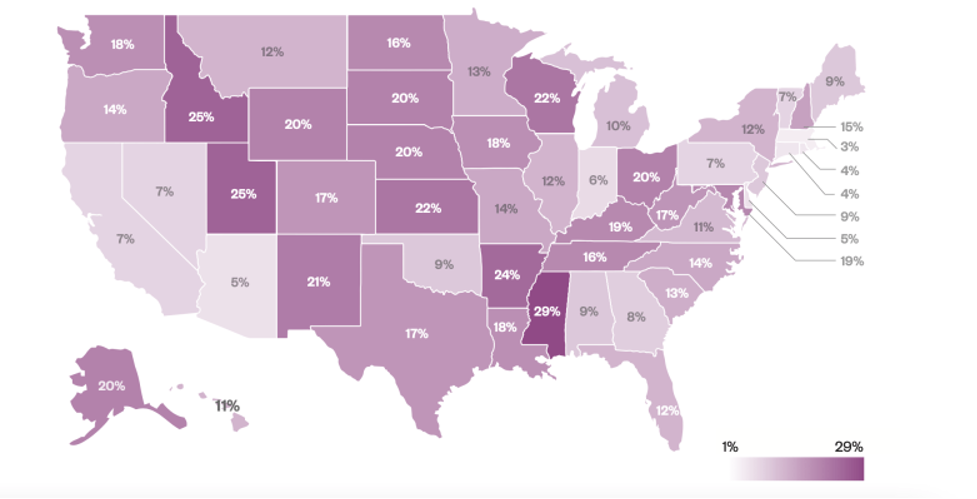

- States with very high rates of college completion from their dual enrollment programs, such as Delaware, Georgia, Mississippi and New Jersey, tend to serve fewer Black, Hispanic and low-income students. Florida stood out as an exception. CCRC’s Velasco noted it had both strong college completion rates while serving a somewhat higher proportion of Hispanic students.

- In Iowa, Texas and Washington, half of all dual enrollment students ended up going to the college that awarded their dual enrollment credits.

- In Montana, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Wisconsin, dual enrollment students have become a huge source of future students for community colleges. (A separate cost study shows that some community colleges are providing dual enrollment courses to a nearby high school at a loss, but if these students subsequently matriculate, their future tuition dollars can offset those losses.)

And that perhaps is the most worrisome unintended consequence of the explosion of dual enrollment credits. Many bright high school students are racking up credits from three, four or even five college classes and they’re feeling pressure to take advantage of these credits by enrolling in the community college that partners with their high school. That might seem like a sensible decision. It’s iffy whether these dual enrollment credits can be transferred to another school, or, more importantly, count toward a student’s requirements in a major, which is what really matters and holds students back from graduating on time.

But a lot of these students could get into their state flagship or even a highly selective private college on scholarship. And they’d be better off. Dual enrollment students who started at a community college, the report found, were much less likely than those who enrolled at a four-year institution to complete a bachelor’s degree four years after high school.