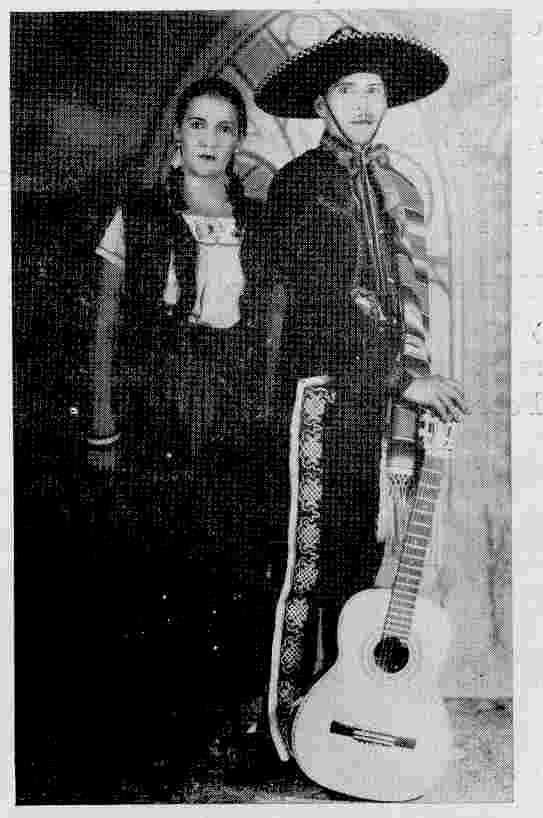

Moreno also remembers her mother, Carmen, leaving on tour, wearing elaborate costume jewelry and embroidered skirts. Her father, Luis, had a pencil-thin mustache that peeked out from under a wide mariachi hat. He had come to the U.S. as a young man in 1919, escaping the Mexican revolution.

“He was wounded in the revolution,” Moreno says. “My brother and I used to touch the bullet hole scars on his rib cage on his right side, and on his thigh where he was shot and left for dead.”

But Luis Moreno, who was largely illiterate, didn’t make much money on his songs, even those that were recorded by stars like Pedro Infante and went on to become super hits.

“They would present a work-for-hire paper for him to sign, in English, relinquishing all the rights,” says Moreno. “They would dangle 10, 15 dollars in front of him.”

Moreno’s parents eventually moved to Fresno, where they became farmworkers to supplement their musical income.

Moreno went on to act in Hollywood, and recorded with major labels as “Carmen.” But she couldn’t accept the stereotypical roles available to Latina actresses in the 1970s. And she refused to anglicize her name or ignore her Mexican musical heritage.

“I figured, if I’m going to do my own thing, I’m going to do my own thang, honey, and I’m going to do it and sing about what I want to,” she says. She formed her own independent label, and financed herself. She struggled as a single mom, raising three kids as a musician.

“I was not above getting a gig in a Mexican restaurant, with a sound system, with a tip jar, and singing all the music that my parents had taught me. I worked in every taco joint in the Coachella Valley,” Moreno laughs.

“She wasn’t willing to sacrifice her musical principles. She marched to her own guitar, or guitarra,” laughs Dr. Manuel Peña, a retired professor of ethnomusicology from Fresno State and UT Austin who specializes in Chicano music. He compares Carmencristina Moreno to stars like Lydia Mendoza or Linda Ronstadt.

“They attained more notoriety and fame, but Carmencristina is every bit their equal,” says Peña. “She’s right up there with the foremost of our Mexican-American artists.”

What makes Moreno different, he says, is the way she sets lyrics in English to a musical framework rooted in Mexican ranchera music.

“That’s hard-core, working-class Mexicano music. But there are other layers of musical development that are superimposed over that ranchera core. That fusion or synthesis, really. She is not the only one to do this, but she is unique in doing it with a single voice and a guitar.”

Carmencristina Moreno was awarded the nation’s highest folk art honor when she was named a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellow in 2003. The award recognized her musical contributions to the farmworker movement, and her project teaching Mexican and U.S. history through music in Central Valley schools.

Now, at close to 75, Carmencristina Moreno is not slowing down, though she’s survived breast cancer and is nursing a shoulder injury after 60 years of holding an acoustic guitar. She’s finishing a book about her father’s experience in the Mexican Revolution, which includes 2 CDs. She lives in her parents’ ramshackle house surrounded by raisin vineyards and almond trees, still composing and playing guitar every day, and taking whatever gigs she can get.

“I can only say Carmencristina richly deserves to be known,” says Peña. “She’s like the treasure of the San Joaquin that hasn’t been discovered yet.