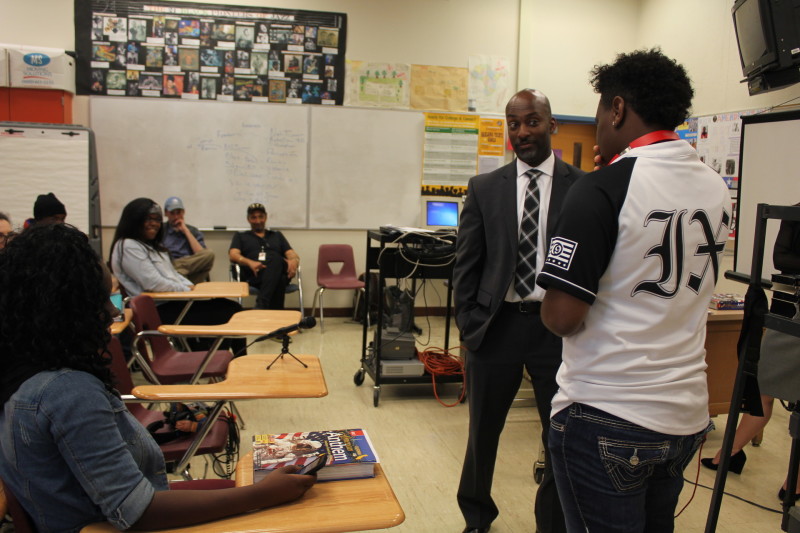

“Good morning, My name is Brendon Woods, Jennie's boss,” Woods says, introducing himself to the class as Alameda County's first African-American public defender.

“We're here to talk to you about L.Y.R.I.C.”

He tells the class of mostly black and brown students that the L.Y.R.I.C. program stands for Learn Your Rights in California. He says it’s something that has personal meaning for him.

“Because when I was your guys’ age, I got stopped and harassed all the time,” Woods explains. “And it's important for me to make sure that you guys know your rights and are able to assert them.”

Deputy Assistant Public Defender Jennie Otis hopes that helps keep kids out of the system.

“I think it plays many roles," Otis says. "One is hopefully to reduce our clientele.”

Public defenders are here for two hours every Friday, using skits and role-playing to teach the students.

National Spotlight on Interactions with Law Enforcement

While the program started last spring, Woods and Otis say kids are more engaged than ever, thanks to the spotlight on recent events in Ferguson, New York and Baltimore in which young black men were killed by white police officers.

Those events raise questions, such as: “The dude that got choked and he died, he had a friend that was recording ...”

Early on, one student asks whether you can get in trouble for filming video of a police encounter like the one involving Eric Garner, the unarmed New Yorker who died in police custody.

“So, if you're further away and recording, it can be OK. It really depends on the officer's interpretation as to whether you're actually interfering with the investigation or arrest,” explains Woods.

It turns out the students, like most people, are pretty fuzzy on even the basics.

“So, true or false,” asks Otis. “I have to speak to a police officer just because he or she wants to talk to me. Who thinks that's true?”

False … with a caveat: You do have to provide your name and date of birth.

Even so, Otis tells the class you can't just walk away until you confirm you're not being detained.

“What we recommend is that as soon as a police officer comes up and begins talking to you, that you say, ‘Am I free to go?’ " says Otis. “And if the officer says yes, then we recommend you say, 'Thank you, officer,' and go on your way.”

Many kids are inclined to comply with authority figures, which can get them into trouble. To help them get comfortable with asserting their rights, Woods and Otis role-play with students, like Yonatan Daniel.

“Nice day today?” asks Woods, playing a police officer.

“Ya, it's good,” answers Daniel

“Where you coming from?” continues Woods.

“Over there,” says Daniel.

“Over there? What friends were you with?” asks Woods.

“I was with my brother,” answers Daniel, as others students in the class begin to shout that he’s giving up too much information.

“What's your brother's name?” persists Woods.

“Jamari,” says Daniel.

“Jamari what?” Woods asks just before Otis interrupts with a “Timeout!”

Otis explains that sort of over-sharing can quickly and needlessly escalate a situation. Say, two men committed a robbery "over there," and you happen to be holding a big bag.

Practice is Key

The key for kids like Daniel and classmate Hyniah Johnson, who says she had a similar experience just this week, is practice.

“Am I free to go?” asks Johnson, to Otis’ praise.

“Good. How does that feel?” asks Otis.

“It was weird,” admits Johnson, “but it felt better than Wednesday.”

They also talk to kids about what to do when the answer is, "No, you're not free to go."

“When he says, ‘Give me your bag’, what do you do?” Otis polls the class.

“Give it to him!” they shout.

“And?” she asks.

“I do not consent to this search,” they answer in unison.

“Do you pull away? Do you slap his hand?” asks Woods.

“No!” they laugh.

Magic Words

Finally, Woods says he wants them to remember what he calls magic words: “I have the right to remain silent” and “I want a lawyer.”

Daniel says the lesson is relevant to him and his peers.

“I think it is because some of us actually do get stopped by police for stuff, even if we don't do something,” Daniel says.

A spokesman for the Oakland Police Department agrees these are the sorts of conversations that need to be had.

Meanwhile, the man who brought the program to Oakland Tech, counselor and former coach Eric Clayton, says he's eager to have the program in more classes.

“You know, it's stemming the tide,” says Clayton, “That's what we're trying to do, stem the tide by education. And they're doing a phenomenal job.”

As the class wraps up, the students each get a small card to remind them of their rights. Clayton takes a handful, enough for each of his five sons.