Once upon a time there were no homeless people in San Francisco. Or California. Or the country, for that matter. Really. At least not in the way we have come to define “the homeless.”

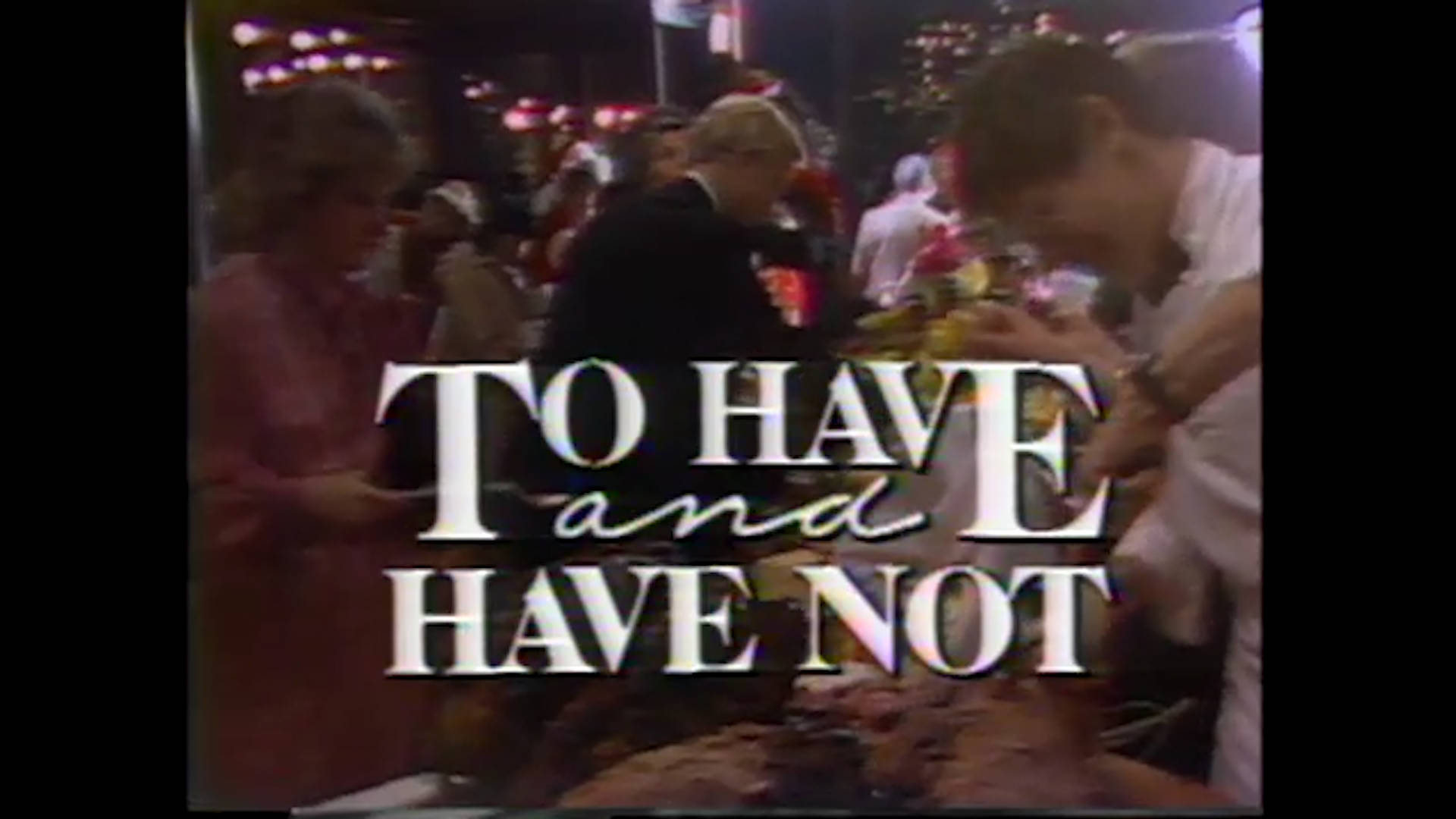

I remember when I first saw homeless people on the streets of San Francisco. It was fall of 1982 and I was producing a local documentary for KQED called “To Have and Have Not” about the growing gap between rich and poor in San Francisco.

Sound familiar?

In the Tenderloin and other run-down corners of the city, my TV crew and I began to notice and speak with people who told us they had nowhere to live. I’d been renting a place in the city for five years. I was accustomed to a few panhandlers downtown, winos and derelicts in the Tenderloin, some runaways in the Haight. But this was different.

Suddenly, St. Anthony’s Dining Hall was swamped with people needing a free meal. Emergency shelters were overrun. At night, people huddled in storefronts in the rain.

“We’re seeing more and more women and children,” Clare Doyle, the director of a Catholic-run soup kitchen in the Mission, told us. “More families. More children who come in here by themselves, sometimes with jars saying, ‘Can I have some soup to take home to my mom?’ ”

This was shocking and it was new. Homeless people in San Francisco. No one was sure how many, but emergency shelters were taking in close to a thousand, while many more eked out a life in the alleys and the parks.