Fair enough.

“Pokemon Go” is a game that relies on augmented reality. Unlike virtual reality, which creates a totally alternate perception, augmented reality overlays virtual information onto the real word. In this case, a map.

He pointed to his phone, and on the screen, a map of where we were standing.

“There are two ‘Pokestops’ on this corner,” said Othenin-Girard pointing to his phone.

Pokestops and gyms are portals where you can capture Pokemon and other goodies you need to play the game. The point is to capture as many as you can.

“There’s one in that tiled trashcan,” Othenin-Girard said as he swiped his screen.

As we walk north on Telegraph Avenue, Othenin-Girard shows me his phone, and his screen is crowded with Pokestops and gyms.

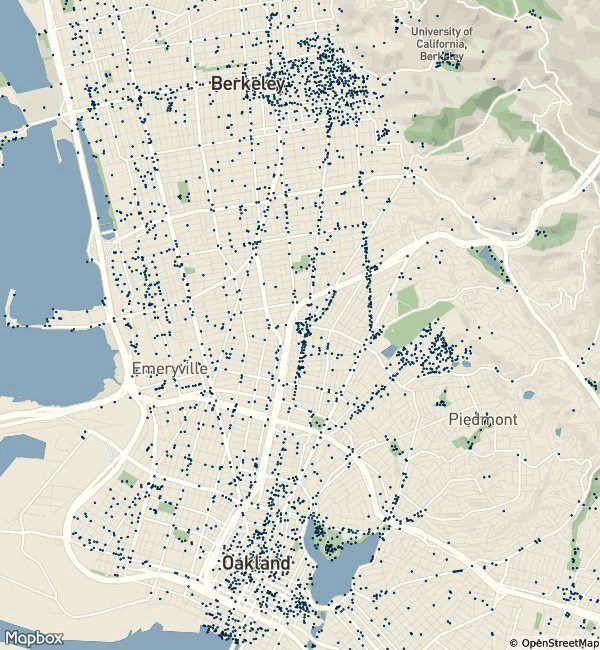

“There are more of them as we go towards Berkeley, but look at what happens if we turn around,” said Othenin-Girard. He turns his back on Berkeley, an increasingly white and affluent city, and points his phone toward a part of Oakland that’s still mostly black and low-income.

The Pokestops and gyms are further apart and in the far-off distance, they seem to disappear.

“And I know for a fact because I live down there, the further down Telegraph away from Berkeley you go, the fewer Pokestops there are,” Othenin-Girard said.

What we were seeing was reflected in a report published by the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. Co-author Tanaya Srini says they looked at the distribution of Pokestops and gyms in Alameda County.

“What we found is 34 Pokestops and gyms on average for white-majority neighborhoods compared to 25 for white minority neighborhoods,” Srini said.

And the trend holds true for Washington, D.C. and other cities. So, why do we care?

Shiva Kooragayala, who co-wrote the study, says “Pokemon Go” has become more than just a game, it’s actually changing behavior. Pokestops and gyms are often in popular commercial districts.

“And so people go to these restaurant and bars because they want to go level up,” Kooragayala said. “And because they’re more likely to be in white majority neighborhoods, that actually has economic consequences on where people go to spend their money.”

Back in Oakland, Othenin-Girard and I go into Rosamunde, a popular sausage grill and beer house that sits on the corner near two Pokestops. I poked my head into the kitchen and met Emelyn Parker. She’s a bartender and works the grill.

I asked her if she’s seen people playing “Pokemon Go.”

“Yeah, they come out in groups and do their Poke thing,” Parker said.

Parker says Rosamunde has seen an uptick in business since the game was released earlier this summer. But Othenin-Girard says it’s a different story in his West Oakland neighborhood.

“We’re in a pretty literal dead zone in the game,” Othenin-Girard said.

So why aren’t there as many Pokestops in predominately black neighborhoods? Othenin Girard says “Pokemon Go” relies on maps that were used in an earlier game called “Ingress.” Those maps were crowdsourced. And in the Bay Area he suspects the crowd was made up of mostly white techies.

“By crowdsourcing from a really specific group of people, it meant that people who weren’t in the group aren’t really well served,” Othenin-Girard said.

And he says, as Silicon Valley develops new technologies, “Pokemon Go” points out some important blind spots that need to be addressed.

This story is part of our ongoing series on Techquity: Diversity, Inclusion and Equity in Silicon Valley.