ATWOOD: There was a very involved black press in L.A., with three major black newspapers. Those sportswriters pushed really hard for the team to integrate. No West Coast city had a major pro franchise until the Rams moved in 1946. They were trying to get a lease for the L.A. Coliseum. This was a moment when the black sportswriters knew they could pressure the L.A. Coliseum commission to potentially withhold a lease until the team tried out black players.

Your book traces how racial covenants were playing out in L.A. at the time. There were these racially restrictive housing covenants.

ATWOOD: At one time, it was estimated that 80 percent of the housing in Los Angeles was covered by racially restrictive housing covenants. That meant black residents, and Asian, Latino, Catholic or Jewish residents wouldn't be allowed to rent or buy in certain areas. That was playing out at the same time football was integrating. Some of Kenny and Woody's peers in the sports world, including two boxers, were told they had to leave their properties. Nat King Cole is another example of someone who was evicted because of these covenants. On the national scene, this was all playing out during a backlash after World War Two, when there was a rise in attacks and lynchings, including against black service members. A lot of these attacks happened in 1946, which was the same time Kenny and Woody were preparing to step out on the field for the L.A. Rams.

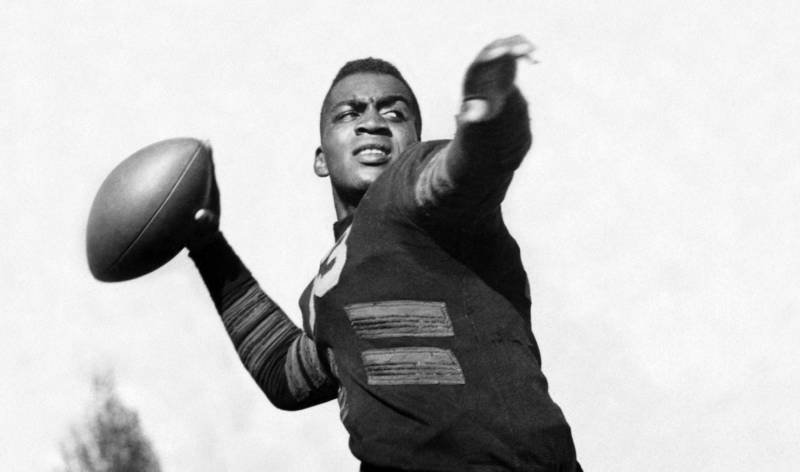

In researching your book, you talked to family members, like Karin Washington Cohen, Kenny Washington's daughter. We called her up, too, and she told us some of her dad's experiences on the field.

"He was the target out there," Cohen said. "They stepped on his hands. They ground the chalk on the field into his eyes. I think he just took that as part of the job. Not just the football playing job, but the job of being the first black guy out there. He was a very good target."

ATWOOD: Kenny and Woody faced hostility from just about everyone. Some fans were supportive, some were very hostile. Opposing coaches were hostile. So were opposing players. There's a scene in the book where Kenny's out of the play, and on the ground, and one of the opponents runs by him and takes a swing with his foot to kick him in the head.

What do you think Kenny Washington and Woody Strode would make of Colin Kaepernick's protests on the field today?

ATWOOD: They didn't have the luxury of protesting, in a sense, because they had to "go along to get along," just to stay on the team. If they did anything like Colin did, the teams would have cut them. I think they would be supportive of the general belief, but they probably wouldn't be able to connect that well with the idea that here is a guy who can actually take that stand.

Why have we heard so much about Jackie Robinson, yet Kenny and Woody's stories have been largely ignored?

ATWOOD: First of all, football wasn't as popular as baseball at the time. But also, Kenny and Woody's stories can't be told as tales of unabashed triumph over racism. Jackie did end up winning the World Series, did get an MVP, had a long career. Kenny and Woody were both near the ends of their career when they were signed by the Rams, because when they were at their peak, the NFL wasn't yet signing black players. They didn't have the same level of success. So what their stories do is to challenge the idea that racism was overcome when it was faced, and also the idea that if you hard enough, you can succeed, the American Dream. They tried just as hard as Jackie. In many ways, they were just as talented as Jackie.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.