Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: Hey guys, I want to introduce you to our Bay Curious question asker this week, and I have to warn you… he’s a little shy.

Kolten Wong: My name is Kolten Wong and I love dinosaurs.

Daniel Potter: Kolten, how old are you?

Kolten Wong: Five!

Olivia Allen-Price: This is Kolten Wong. We met him last year at the Bay Area Science Festival. It’s this huge event at AT&T Park, and thousands of kids were there to learn about all things science. The Bay Curious team went to get questions—and Kolten’s really stood out.

Kolten Wong: What dinosaurs lived in the Bay Area?

Olivia Allen-Price: So, what dinosaurs used to roam the Bay Area? Science reporter Daniel Potter went to meet Kolten and his mom, Annie, at their house in Daly City.

Daniel Potter: Can you say it one more time, just to make sure I have it?

Kolten Wong: How many dinosaurs in the Bay Area?

Daniel Potter: I’m gonna work on finding out.

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on Bay Curious, we’re going back in time … like way, way back… to discover California’s dinosaurs, and other prehistoric creatures. This episode first aired in 2017, but it continues to blow my mind even today. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. We’ll get started after this break.

[SPONSORSHIP MESSAGE]

Olivia Allen-Price: Five year old Kolton wants to know: What dinosaurs used to roam the Bay Area? Let’s explore the prehistoric past around San Francisco long before it was a city…

Daniel Potter: Or, turns out, even before it was on dry land.

Olivia Allen-Price: Now, Daniel, before we dive in I think we should lay out your extensive credentials for everyone. After all, you and Kolten share a deep love of dinosaurs.

Daniel Potter: A mild obsession…Okay, I grew up rocking dinosaur shirts, had tons of books, my toy collection was peak jurassic park. These days I read up and go to museums and do stories about them, when I can. I draw stegosaurus on napkins, I own more than one pair of dinosaur socks. Kolten is similar. He has the shirts, the books, the toys:

Daniel Potter: What’s that?

Kolten Wong: A triceratops that does this:

[toy roars]

Olivia Allen-Price: So Kolten wanted to know what dinosaurs used to stomp around his neighborhood.

[thunderous stomping]

Daniel Potter: It turned out the answer was easy—zero dinosaurs.

Olivia Allen-Price: Whomp whomp.

Daniel Potter: But the reason is highly neat. And, this story does have lots of rad prehistoric beasts.

[roar]

Daniel Potter: First, we need to explain where San Francisco was during the Mesozoic Era. That’s the geologic time of the dinosaurs, before they suddenly died off about 66 million years ago.

Doris Sloan: Through all of the Mesozoic, the Bay Area as we know it didn’t exist.

Daniel Potter: This is Doris Sloan, a retired geologist from UC Berkeley who wrote a book called Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region.

Doris Sloan: The Bay Area was underwater.

Daniel Potter: So hundreds of feet, thousand of feet deep?

Doris Sloan: Probably thousands.

Daniel Potter: That seafloor wasn’t kind to old bones we’d like to find today. It was a trench, with an ocean plate slowly sliding under the continent and melting. Plus, it was prone to earthquakes, triggering powerful underwater landslides.

Doris Sloan: This would shake a skeleton apart, and the sediments being dragged down into a zone where heat and pressure would metamorphose them—All of this argues that you wouldn’t get much preserved.

Daniel Potter: California is, in a lot of ways, messier, more challenging to tease apart.

Doris Sloan: Good way to put that, messier. Certainly more mixed up and scrambled and there’s not a lot of layer-cake geology in California.

Olivia Allen-Price: Still, a few Mesozoic fossils did survive.

Daniel Potter: In the Marin Headlands, you can spot radiolarian chert. It’s a reddish rock made up of crumpled layers of tiny ancient shells—think of plankton—called radiolarians. A few larger spiral shells from extinct mollusks have also shown up. They belonged to ammonites, which swam through the water kind of like the modern-day nautilus.

Olivia Allen-Price: Alright Daniel, there’s a five-year-old kid waiting for nasty big pointy teeth.

Kolten Wong: Yes!

Daniel Potter: We’re on our way… So while the Bay Area was deep underwater, the coastline was a hundred miles further east. Picture a shoreline toward the Sierra foothills. I made the long drive to a museum out that way, on the other side of Sacramento. That’s where I met this guy:

Dick Hilton: My name’s Dick Hilton, and this is Sierra College. And I’m co-chair of the Sierra College Natural History Museum.

Daniel Potter: Hilton’s book is titled Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Reptiles of California.

Olivia Allen-Price: Shipping weight: three and a half pounds.

Daniel Potter: What’s different between a Mesozoic reptile and a dinosaur?

Dick Hilton: Well a dinosaur, first of all they’re terrestrial. They’re totally terrestrial…

Daniel Potter: Terrestrial. This is why the Bay Area didn’t have dinosaurs stomping around: it was underwater, so whatever passed through was either swimming or flying. Not a dinosaur per se.

Dick Hilton: So it’s the skull, it’s the hip structure that sets them apart from other reptiles.

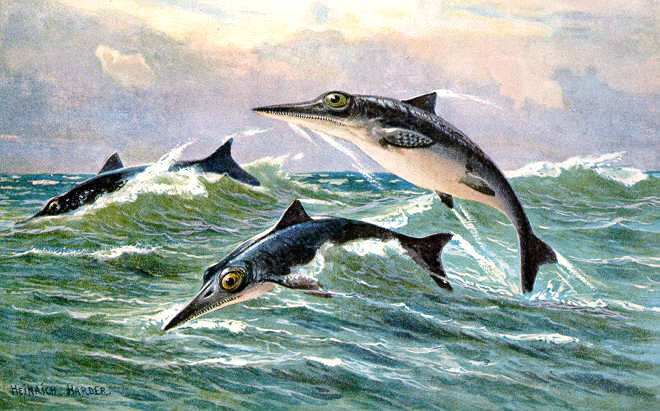

Daniel Potter: Hilton says all kinds of reptiles that weren’t dinosaurs swam along the coast, chowing down on fish and ammonites. One resembled dolphins,

[dolphin screech]

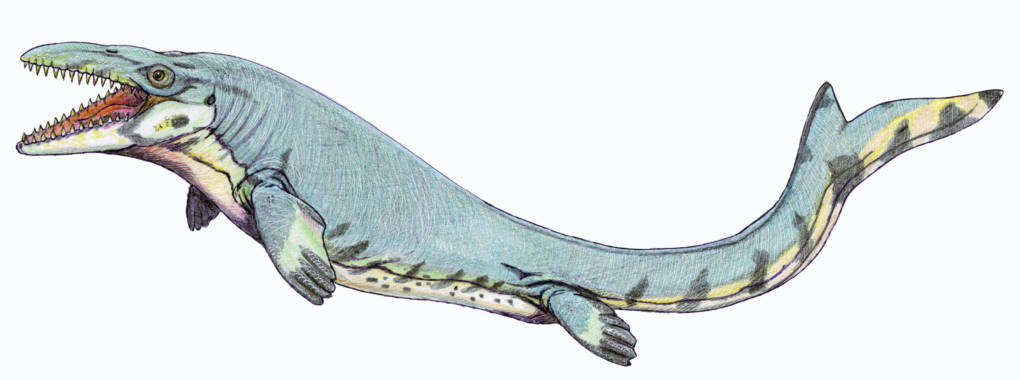

Daniel Potter: If dolphins were terrifying reptiles. That’s ichthyosaurus. The name literally means fish lizard. Another toothy predator upwards of 30 feet long was mosasaurs…

Dick Hilton: If you saw the latest Jurassic Park movie, one of these comes out of the water and scares the heck out of you.

[Jurassic World clip]

Dick Hilton: This one was found right here, three miles south of the college…

Daniel Potter: Also, one with four flippers, a long neck, and sharp teeth– Plesiosaurus.

Dick Hilton: And everybody says “Well what’s that?” And I always refer them to the Loch Ness monster.

Daniel Potter: When I first visited Kolten and asked about his favorites, he reached for a toy plesiosaur.

Dick Hilton: What’s interesting is they will come up on the beach with their long neck and scoop up rocks and swallow the rocks.

Olivia Allen-Price: Alligators and crocodiles do the same thing today. The stones are called gastroliths.

Daniel Potter: Some animals do it for digestion, but Hilton thinks plesiosaurs did it for neutral buoyancy.

Dick Hilton: You don’t wanna sink to the bottom, you don’t wanna float to the top, so if you can swallow just enough rocks and keep them in your body, then you’re neutrally buoyant and you just glide through the ocean, which is pretty cool.

Daniel Potter: So have these been found then, fossils with rocks inside of them?

Dick Hilton: Yeah, we find them inside the rib cage, nests of rocks … These would’ve been swimming over San Francisco, at one time.

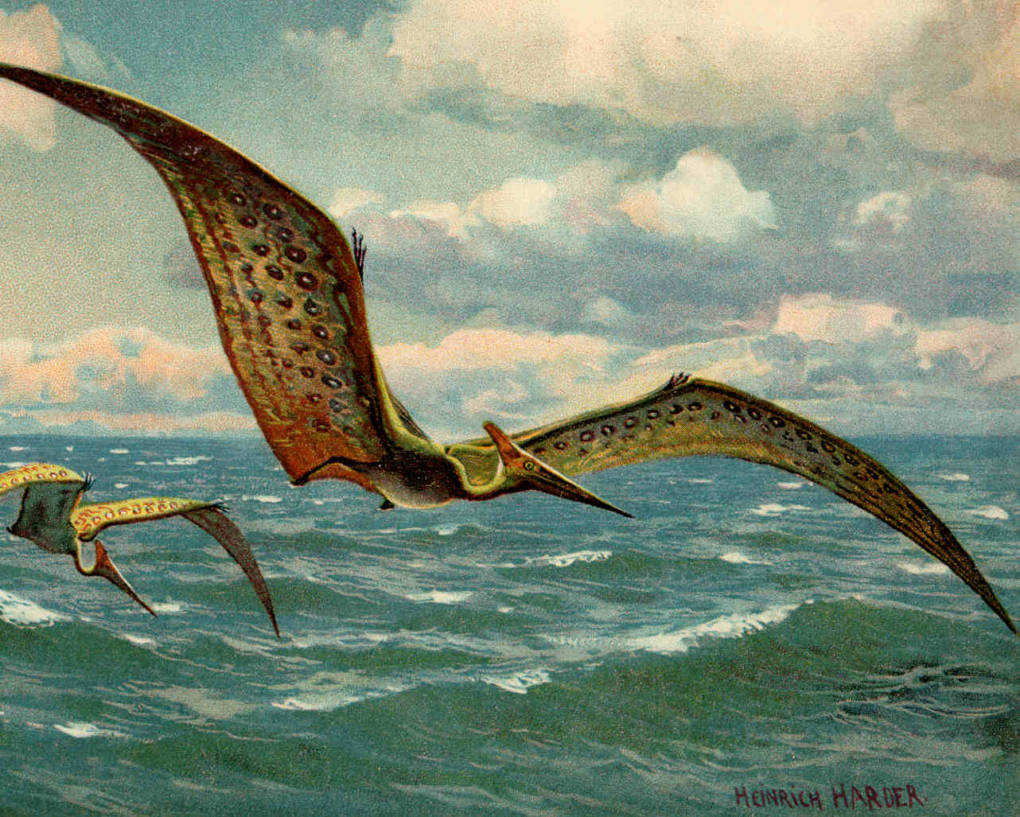

Daniel Potter: More Mesozoic reptiles were overhead, gliding and swooping through the air. The family of the iconic pterodactyl and its cousin, the pteranodon.

Dick Hilton: The largest ones may have had a wingspan of around 40 feet, so we’re talking of a flying reptile here the size of a jet fighter, which is pretty cool.

Daniel Potter: So is it your thought that pteranodons and other flying reptiles could’ve likely been circling over what’s now Bay Area?

Dick Hilton: Oh of course, yeah. They probably flew way out to sea, they had such huge wingspans.

Daniel Potter: It’s rare to find reptile or dinosaur fossils anywhere near California’s coast. A lot of what Hilton showed me were fragments from further east—a finger bone here, a piece of leg there. But Hilton is convinced, if they were on the Mesozoic shoreline around the Sierra foothills, they were swimming and flying above the modern-day Bay.

Dick Hilton: Undoubtedly. It’s like today. You go along the coastline and you’re liable to see whales, okay? And they stay usually fairly close to the coastline. But you can go out on a boat 500 miles from the shore and still see whales and still see birds, just probably not as numerous.

Daniel Potter: So I reported this back to Kolten the next day.

Daniel Potter: Have you ever seen a whale from the beach, Kolten?

Kolten Wong: Yes.

Eric Wong: Yeah, we saw one. Where?

Kolten Wong: Hawaii

Daniel Potter: You saw a whale from the beach when you were in Hawaii?

Kolten Wong: Yes.

Daniel Potter: We were on campus at Berkeley for an open house at the Museum of Paleontology, which has triceratops skulls, a pteranodon and a huge T-Rex. Kolten also pointed out the skull of a member of the duck-billed dinosaur family, the hadrosaurs, to me and his mom Annie.

Annie Wong: What’s that one again, Kolten? I don’t know.

Kolten Wong: A parasaurolophus!

Annie Wong: How did you recognize that?

Kolten Wong: Cause its crest.

Annie Wong: The crest?

Kolten Wong: Yes!

Daniel Potter: Related hadrosaurs are among the few dinosaur skeletons found intact in California, at least so far. Lawmakers are considering a bill to make one such duck-billed herbivore the state dinosaur.

Olivia Allen-Price: So how’d we do? Was Kolten satisfied?

Daniel Potter: I feel like we’ve covered a lot of ground, what do you think?

Kolten Wong: Yes.

Daniel Potter: Enough to call it a podcast?

Kolten Wong: Yes!

Daniel Potter: Thanks, Kolten.

Kolten Wong: Thank you.

Olivia Allen-Price: Alright, that’s Bay Curious. Daniel Potter, thanks so much for the story.

Daniel Potter: It was fun! Quick thanks to Lisa White, Paul Renne, Kevin Padian, Charles Marshall, Danna Staaf and Matthew Clapham, all experts who helped background this story. Thanks especially to Kolten, Annie, Eric and the entire Wong family. Thanks also to Lisa Pickoff-White and Craig Miller.

Olivia Allen-Price: If you’re new to Bay Curious, welcome! Please consider subscribing so you don’t miss a future episode. And if you like what you’re hearing, share it with a friend!

Olivia Allen-Price: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. The show is produced by Amanda Font, Ana De Almeida Amaral, Christopher Beale, and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Additional support from Jen Chien, Katrina Shwartz, Holly Kernan, and the whole KQED family. And we were trying to think of a send off that was related to dinosaurs but we were drawing blanks.

Daniel Potter: We’re glad you saurus.

Olivia Allen-Price: How about just like… roaaar! No?

Daniel Potter: Nailed it.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price, I’ll see you next week.