Manson was also married twice before the age of 30, and had one child from each marriage — both of them named Charles. Those marriages felt apart amid Manson's regular stints in prison.

While he left school at an early age, Manson professed admiration for the utopian science fiction of Robert Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange Land." During his time behind bars, he also learned to play the guitar, a skill he would use to draw followers to him.

When he was released from a California prison in 1967, Manson moved to San Francisco, where he began to recruit the first followers who would come to be members of his "family" — mostly young women, some of whom later took part in the 1969 killings.

Biographer Jeff Guinn says that during this time, Manson fed off the free-love culture of the city, especially in the Haight-Ashbury district.

"Haight-Ashbury is overflowing with children who don't know where they're going, what they're going to do, what they're going to eat next," Guinn told Fresh Air in 2014. "But they've come in search of some guru to be able to tell them what to do and make their lives better. And that's who Manson preys on."

Guinn says that oddly enough, Manson cribbed much of his sales pitch from a best-selling motivational book, which was a cornerstone of the era's polite society.

"Every line he used, almost word for word, comes from a Dale Carnegie textbook in a class, 'How to Win Friends and Influence People,' " Guinn told All Things Considered in 2013.

Manson had learned Carnegie's guidelines in prison, Guinn says, and applied them in distorted fashion on the streets of San Francisco.

Eventually, Manson took his followers on the road, transforming them into a traveling commune in an old school bus. But all the while, through violence, emotional manipulation and the administration of the drug LSD, Manson sought to instill a belief in his followers that he was a messianic figure.

By the time Manson settled with his group at the Spahn movie ranch northwest of Los Angeles, he had them firmly in thrall.

Helter Skelter

It was there, in the isolation of the ranch, that Manson polished his apocalyptic theories of an approaching race war between white people and black people. Manson's cult was to wait out the war in the desert, returning only to lead the new world order after black people had won.

According to Bugliosi, who later prosecuted the case against Manson, the cult leader gleaned what he believed were clues in the biblical book of Revelation and the Beatles' self-titled 1968 album, which he would listen to on repeat at the ranch. In songs such as "Piggies," "Blackbirds" and "Helter Skelter," Manson heard a prophecy of the race war to come.

All the while, Manson pursued an ill-fated music career of his own. Despite his acquaintance with Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, Manson failed to achieve any measure of success in recording.

Things came to a head in the early morning of Aug. 9, 1969, just after midnight, when several of his followers descended on the home actress Sharon Tate shared with her husband, director Roman Polanski. There, they killed the actress, along with four others present at the home — including Abigail Folger, the daughter of Folger Coffee chairman Peter Folger, and Steve Parent, a clock radio salesman who had been visiting the house at the time.

They shot Parent and beat and stabbed the other victims to death. After the attack, they scrawled the word "pig" in blood on the front door.

The next night, members of the Family — this time under Manson's direct supervision — attacked the home of grocery store owners Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, killing the couple and writing more messages -- "Death to pigs" and "Rise" -- on the wall. On the refrigerator, they scrawled "healter skelter" — a misspelling of the Beatles' song title.

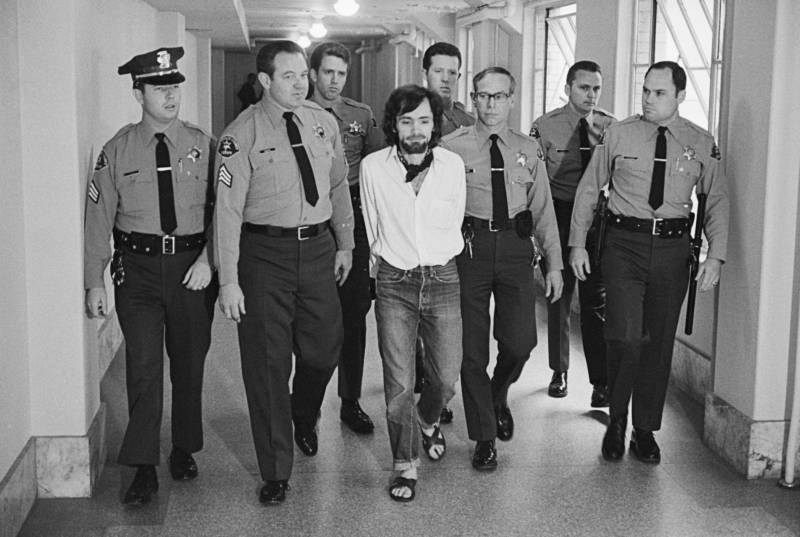

The violence went unsolved for months, until a series of interlocking clues led investigators back to Manson. During the trial that followed, which began in 1970 and lasted for more than nine months, the prosecution unraveled what they found to be Manson's motive: to pin the murders on black people, and in so doing, accelerate the race war he envisioned would follow.

Ultimately, Manson was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in 1971, along with three of his followers. Another Manson follower, Charles "Tex" Watson, was later also convicted and sentenced to death.

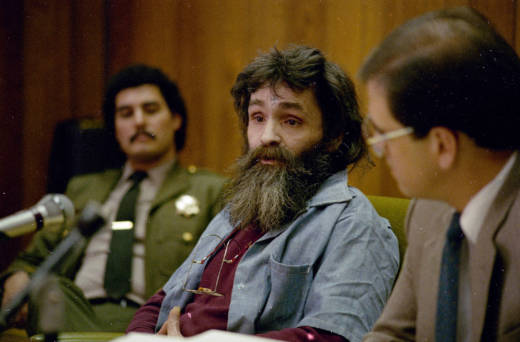

In 1972, when the California Supreme Court found the death penalty violated the state Constitution, the death sentences for Manson and his followers were commuted to life in prison. And there he stayed for nearly a half-century. As recently as 2012, Manson was denied parole for the final time. His next parole hearing had been scheduled for 2027.

Still, though Manson lived behind prison walls for decades, his name — and the violence for which it became shorthand — rarely strayed far from books, film and even music. How is it that the Manson Family murders have held such an enduring place in American lore?

For that answer, one might turn to Bugliosi, the prosecutor who helped put Manson away and who co-wrote the 1974 book "Helter Skelter" that enshrined Manson's legacy. Some years before Bugliosi's death in 2015, he told NPR why he thinks interest in Manson endured.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))