"With these numbers of homes increasing, the problem is going to get worse."

The reason it is so dangerous for people to live in the wildland-urban interface is the same reason people want to be there in the first place.

“People want to live close to nature,” said Ray Rasker, the head of Headwaters Economics, a nonpartisan research group in Montana that has studied wildfire and land use policy. “It’s also, no one is telling them not to.”

But people living in homes buried deep within canyons, perched on hillsides or abutting national forests are more likely to start fires. Sparks thrown from roads, power lines, unattended barbecues or cigarettes have more fuel to burn in these areas. In California, it is people who are responsible for nearly every single wildfire: 95 percent, according to a recent study.

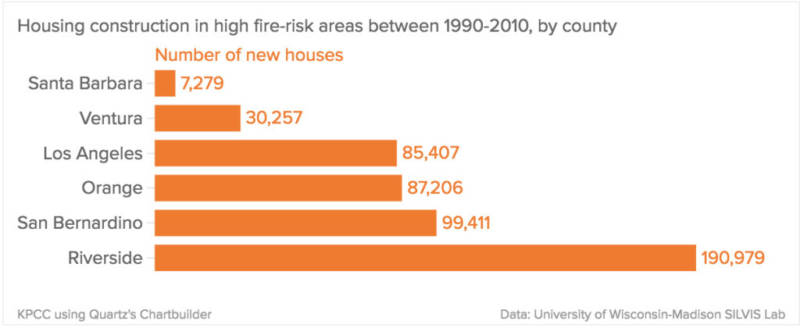

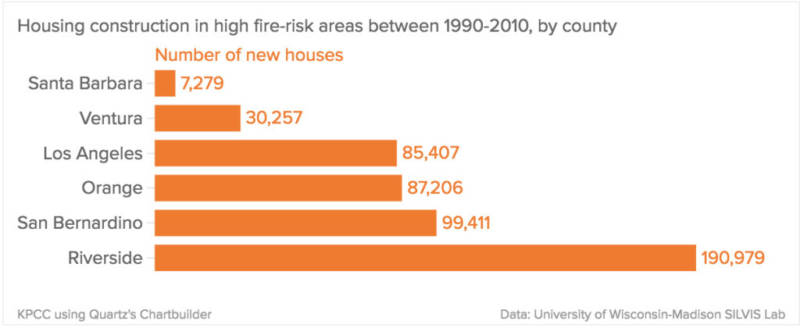

And after houses burn, people generally want to rebuild. Radeloff found that between 1990 and 2010, the number of new houses constructed in the footprint of old wildfires increased 62 percent, outpacing the average U.S. housing growth rate of 29 percent.

“That’s a stunning growth rate,” he said.

Indeed, people are already beginning to rebuild in the footprint of last year’s destructive Thomas and Wine Country fires. Some are in areas designated “high fire hazard severity zone." Those are places the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection has determined most likely to burn. But new structures there have to be built according to modern building codes designed to make houses more resistant to embers and flames. If the homes that burned are outside those zones, as many houses in the footprint of the Wine County fires are, they don’t have to comply with state codes.

But if people are exacerbating wildfires by building in places prone to them, then people can fix the problem, said Jon Keeley, a scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey who researches wildfires and is not affiliated with the paper.

“Climate change is something the average person feels they can have no control over,” he said. “Population growth and planning issues, these are things people can have impact on.”

Some Southern California counties, like Ventura and San Diego, have strict enforcement of vegetation clearing rules, and will fine homeowners who do not comply. Rasker said more policies like these are needed to reduce the risk of living in the wildland-urban interface. Ultimately, he believes the crux of the problem is that decisions about where to build houses are made at the local level, while the consequences of those decisions are largely borne by state and federal agencies who foot the bill for firefighting costs.