“Managing all the forests in every way we can does not stop climate change and those who deny that are definitely contributing to the tragedies that we are now witnessing and will continue to witness,” Brown said.

Scientists who study fire agree and say both a changing climate as well as how people have managed forests has created a new environment for big fires to thrive.

The global average temperature is more than 1 degree Fahrenheit higher than it used to be before the Industrial Revolution. And in a dry climate more heat equals more drying. Meaning: The hot dry air literally sucks the moisture out of the ground and out of vegetation.

“And it doesn’t take much,” says Jennifer Balch, a fire ecologist at the University of Colorado. “With just a little bit of drying you get a substantial increase in the amount of burning.”

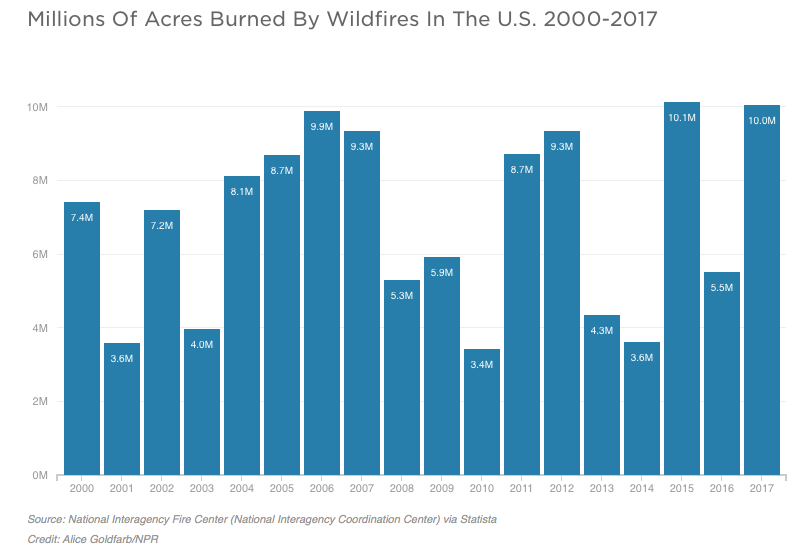

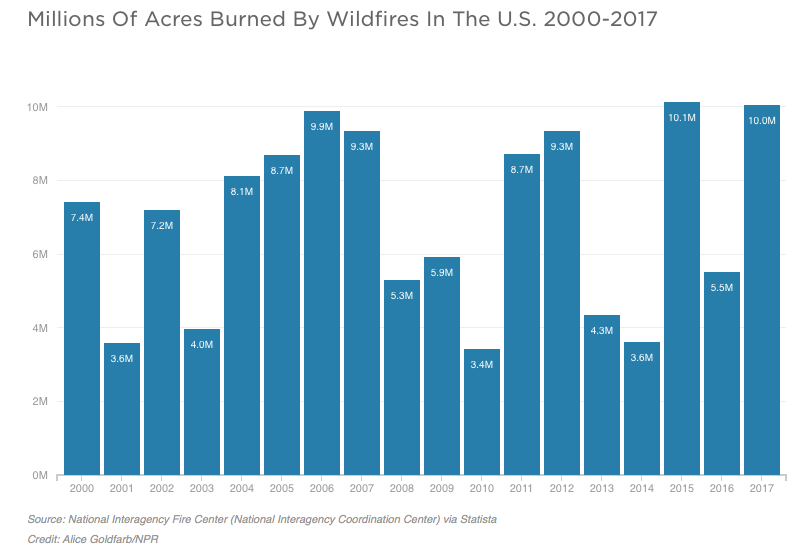

In fact, the number of large fires across the Western U.S. has increased five-fold since the 1970s, says Balch.

Scientists say the warming climate has already caused a smaller snowpack in California’s mountains as well as a reduction in the amount of fog that rolls in off the Pacific Ocean. Both lead to drier vegetation, says Balch.

Human carelessness has also contributed to increased fire activity in the West, says Balch, noting that 84 percent of wildfires in the U.S. in the past two decades have been started by people.

They’re also putting themselves more at risk, she says. “We … have more and more people moving, literally building homes, in the line of fire,” says Balch. “And today there are about 1.8 million homes at high fire risk across the Western U.S.”

In addition to wildfires becoming more frequent — California’s fire season is almost year-round now — scientists have also found that the fires are becoming bigger.

It’s relentless, says Malcolm North, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service.

“In much of California we’re getting to a pretty much year-round fire season as in the past it used to be limited to five or six months out of the year,” says North.

Dry weather and strong winds also mean that what would have been small fires in the past are now monster fires that both damage trees and climb up into the canopy and kill whole forests, says North. This is due in part to the fact that forest managers have spent the last century putting out every fire they could, even small, natural fires, he says, and the forests have became choked with too much overgrowth, making them ready to burn.

Additionally, North says hurdles such as steep slopes, protected wildlife and complaints from homeowners about smoke limit how much federal and state mangers can thin or do controlled burns in forests.

“Literally probably 80 to 90 percent of these dry, mid-elevation forests are chock-full of fuels that really drives high intensity fire,” he says.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))