Originally Published Dec 7, 2018

L

isa Abramson says that even after all she’s been through – the helicopters circling her house, the snipers on the roof, and the car ride to jail – she still wants to have a second child.

Because, in the beginning, when her daughter was born, Lisa was smitten, just like the mom she’d imagined she would be. She’d look into her baby’s round, alert eyes and feel the adrenaline rush through her. She had so much energy. She was so excited.

“I actually was thinking like, ‘I don’t get why other moms say they’re so tired or this is so hard. I got this,’” she says.

Lisa wanted to be the perfect mom. She was ready to be the perfect mom. She’d been a successful marketing executive for a Silicon Valley tech company and a successful entrepreneur. And that first week after her baby was born, everything was going according to plan. The world was nothing but love.

But even when Lisa did get tired, and she got time to sleep, she couldn’t.

Then, the baby started losing weight, and the pediatrician told Lisa to feed her every two hours.

“That meant breastfeed and then pump, and then feed her the pumped milk and then clean the pumping parts, which is always something no one thinks about but takes about 20 minutes,” she says. “Basically, through that every two-hour feeding cycle, I had 10 minutes of downtime.”

Lisa started to feel like she couldn’t keep up. She felt overwhelmed and guilty. Really guilty.

“It weighed on me as ‘I failed as a mom. I can’t feed my child,’” she says. “I needed to feed her, that was the most important thing, and my well-being didn’t matter.”

She was barely sleeping. Even when she could get a release from breastfeeding purgatory, she couldn’t relax. As she got more and more exhausted, she started to get…confused.

“I was having a conversation with someone, their voices were just distorted and it was really hard for me to understand what they were saying.”

She tried going to a spin class, something she loved and had done up until the baby was born.

But 10 minutes in, she was out of there.

“That was not a good idea, because the noises and intense volume of the spin class was really alarming to me. It felt like the walls were talking to me,” she says. “I just said to my husband probably a hundred, 200 times that day, ‘Am I crazy? Am I crazy? Am I crazy?’”

But then, about a month after the birth, her clarity came back. It was like she woke up from a dream. It rained every day for the next week. The day the sun came out, she noticed police helicopters circling over their apartment. She heard them land on top of the building.

“There were snipers on the roof and there were spy cams in our bedroom and everyone was watching me and my cellphone was giving me weird messages,” she says.

Lisa waited for the police to come in and take her. But the next morning, she woke up in her own bed. The cops had arrested the nanny instead.

This was wrong, she thought, the nanny shouldn’t be punished for her crime. Lisa told her husband it wasn’t fair. She was going to put an end to all this. She was going to jump off the Golden Gate Bridge. And that’s when her husband told her he was going to drive her to the police station himself.

“It was like, ‘Oh, okay, he’s taking me in and I guess I’m getting arrested,’” Lisa says. “I remember my mom cooked me eggs and it was like, ‘You should eat these before you go.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, she’s giving me my final meal before I go to jail.’”

From her husband’s perspective, this was one of the worst days of his life.

“I’m bringing my wife to the hospital and then checking her into an inpatient unit. It was really, really challenging,” says David Abramson, relaying what really happened that day.

Not Jail, the Psych Ward

There was no crime, the nanny wasn’t arrested, and Lisa’s destination that day was not jail, but rather the general psychiatric ward of Sutter Health’s California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco – though the hospital didn’t feel far off from where Lisa believed she was going.

“You have to wait for the door to be unlocked, the buzzer, and there’s security and it felt almost like bringing Lisa to jail, even though she didn’t do anything,” David recalls. “That was probably the most heart-wrenching thing, was having to leave her that night with the hospital staff. You could see in her eyes and her body language that she was panicked all of a sudden that we were leaving.”

The other patients were there for drug overdoses or alcohol withdrawal. People were screaming. One patient thought he was a dog, crawling around on all fours, barking. It didn’t seem like the right place for a new mom.

“Probably for the first five days I just didn’t speak to anyone,” Lisa says. “I don’t know if I couldn’t speak or I wasn’t speaking, but I was terrified enough of the environment that I decided I wasn’t going to answer anyone’s questions. I wasn’t going to talk to anyone.”

Lisa still thought this was all part of some conspiracy.

“I just thought I was there because I did something wrong,” she says. “Because I tried to get out to leave and I was locked in so you can’t leave. I was like, ‘Maybe I am in a jail, but it looks like a hospital? They’re saying it’s a hospital, but it’s really a jail?’”

Lisa doesn’t remember any doctors or nurses telling her why she was there or what was going on.

“They’re just like, ‘Take these medications,’ and they’re pissed at me because I wasn’t cooperating and going to any of the groups or talking to anyone,” she says. “No one told me what my diagnosis was, why I was there.”

It wasn’t until Lisa had been in the hospital more than a week that she remembers her husband telling her why she was there. He brought her a print out from the internet on postpartum psychosis.

“That was the first time where I was like, ‘He’s on my side. He made up this disease just to make me feel better. That was so sweet,’” she says.

The papers said it was elevated hormones from childbirth plus sleep deprivation that can trigger confusion and paranoia. Lisa figured it took her husband hours to photoshop all this.

“I really was just like, ‘No. I’ve heard of postpartum depression. No, I have never heard that there’s postpartum crazy.”

New Data on Moms Who Die By Suicide

Postpartum psychosis is real. It’s rare – it affects one or two women out of every thousand that give birth. But experts believe more women are affected than previously thought. And more of them are ending up dead, by suicide.

There are a handful of doctors and researchers trying to figure out why. States have never kept good data on this, so each suicide is like a mystery, and it takes a team of medical detectives to piece it together.

They start with death certificates and coroner reports, then work backward. They track down hospital records to figure out when the woman gave birth. Then they study medical charts for clues, signs of mental illness that the original doctors didn’t catch.

California researchers just finished their first big study like this. The state’s public health department hasn’t published it yet, but The California Report got a preview of some of the data: 99 new moms in the state died by suicide over a ten-year period.

The investigators determined that of those 99 suicides, 98 were preventable.

Nearly every single woman might not have died if the health care system in California had done a better job taking care of them: if women had been screened better, diagnosed better, treated better.

“The work that we do here is less than 10 percent of what needs to be done,” says Nirmaljit Dhami, a psychiatrist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View. She’s one of the doctor-detectives who reviewed the suicides, but she did not talk about the report or share data from it.

She is an expert in postpartum mental illness and often treats women in crisis, cleaning up what OB/GYNs miss. Based on her clinical experience and observations, she says a lot of doctors don’t know the early signs of postpartum psychosis; they don’t know that the symptoms wax and wane.

“A lot of times the patient will present very clearly, then at other times, will present with acute confusion and disorganization,” she says.

Like Lisa Abramson, of sound mind in one moment, then believing the walls are talking to her in the next.

“This is a symptom that clinicians who are not trained in this field can easily miss,” Dhami says, “because when they see the patient in their office with the family, they can think that the patient is normal and is probably suffering from sleep deprivation and discharge them home,” she says.

This is how women die. In the U.S., mental health problems are one of the leading causes of death among new moms, according to a 2018 report from the Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths initiative at the CDC. Mental health problems are number seven on the list, nearly tied with high blood pressure complications. For white women, mental health problems are the fourth leading cause of death.

Even when women do get into care, Dhami says, it’s often inadequate or inappropriate. Doctors prescribe the wrong medications. Insurance companies push patients out of psych units before they’re ready. And the staff at psych units are generally not trained in these illnesses, Dhami says, and they may not be equipped for even the physical needs of new moms.

Take Lisa Abramson’s inpatient experience. When Lisa first arrived at the psych ward, her husband told the resident who admitted her that he thought Lisa had postpartum psychosis. The resident said to him, “Postpartum, what?” He promised David he’d study up on it.

Then, several days into Lisa’s stay, she complained of pain in her breasts. She’d stopped breastfeeding the instant she left home, and it didn’t seem to occur to anyone that her breast would become engorged.

Her husband had to negotiate to bring in Lisa’s breast pump from home. She remembers being put in a room with padded walls that looked like a solitary confinement chamber from a horror movie.

“That was where they sent me to go pump, and under supervision from doctors because they were worried,” she says. “God knows what I would do with the breast pump. A breast pump is a torture device already.”

But the worst thing of all, was not being allowed to see her baby. The inpatient unit has a strict policy: no infants or children on the ward. The hospital says this is intended as a safety measure, for everybody. Her family argued with the staff.

“They said, ‘She’s a new mom and she needs to see her baby. That’s keeping this bond going, it’s really, it’s important,” Lisa recalls, tearing up. “That was the hard part, was not getting to see her.”

About five days into her time there, Lisa’s family was able to negotiate short one-hour visits with her daughter, supervised by a person who kept looking at his watch.

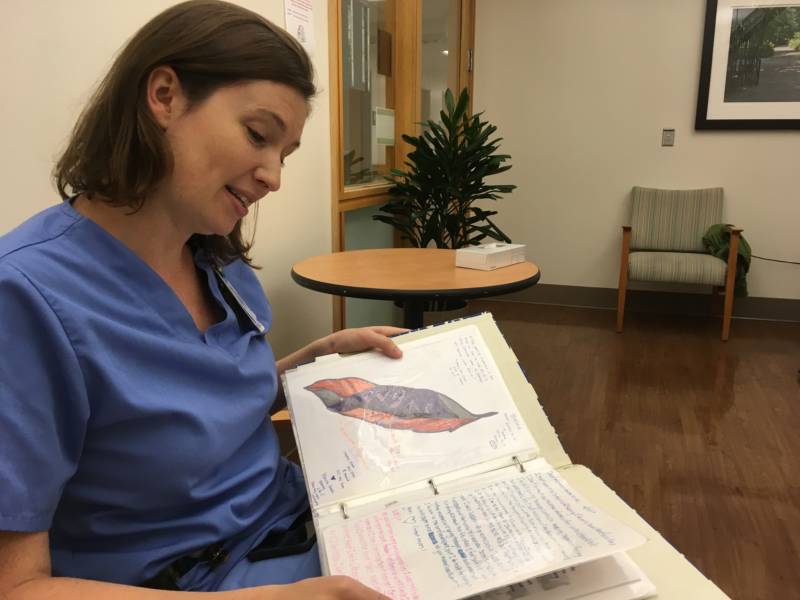

Lisa’s family was so unhappy with her care at the hospital that her husband practically broke her out of there. They found Dr. Dhami and asked her to take over Lisa’s treatment. She enrolled in a comprehensive outpatient program Dhami runs at El Camino Hospital, called the Maternal Outreach Mood Services (MOMS) program, where Lisa could bring her baby along.

Dr. Dhami says separating a mother from her newborn actually makes it harder for the mom to recover.

“A lot of times, symptoms of postpartum depression and psychosis involve the mother feeling that she’s like a bad mom,” she says. “It is a difficult situation for the mother to be in when she has so many negative thoughts and ruminations about herself and her ability to be a good mom.”

Under Dr. Dhami’s care, Lisa started to reclaim her grip on reality, but she didn’t know how long it would be before she’d start to feel better. She wondered if she’d ever feel like herself again.

California Pacific Medical Center declined to comment on Lisa’s case specifically, even though Lisa authorized the hospital to discuss her medical records. The inpatient psychiatric medical director, Dr. Stephanie Wilson, says breast pumps are now available to women who need them, and providers review new moms’ wishes to see their babies on a case-by-case basis.

“We take into full consideration all of the circumstances and the details of that patient, of the infant, and really seeing what, if any, benefit, or even potential harm, it could have to the mother,” Wilson says. “Once the symptoms of depression and psychosis start to get better, that’s when I would start to allow more visitations.”

A Different Kind of Care for Moms

There’s plenty of research dating back to the 1940’s on the ideal protocols for inpatient treatment of postpartum mental illnesses. The gold standard is to admit the mother and the baby into the hospital together, on a specialized mother-baby unit.

They’re treated as a pair. Part of the mom’s therapy is getting guidance on how to read the baby’s cues, and how to meet the baby’s needs as well as her own. At night, the baby sleeps in a supervised nursery, so mom can get uninterrupted sleep. In the United Kingdom, there are 21 of these mother-baby units. In France, there are 15. They’re in Belgium, New Zealand. There’s one in India.

In the U.S., there are zero.

The closest thing there is to a mother-baby unit in the U.S. is 3,000 miles from where Lisa lives – the hospital at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

The perinatal psychiatric unit here is reserved exclusively for pregnant women and new moms. They accept all kinds of commercial insurance and Medicaid, so any woman, wealthy or low-income can get treated here.

When women first arrive, nurses show them the “Dear Mom” book, where women who are close to being discharged write notes to the women just being admitted:

“Dear moms or mom to be: This place has saved my life and it will save yours…

Dear mom: You may think you’re the only “crazy” girl in the world like this, but I promise you, you’re not alone…

Dear mammas, you are strong, you are beyond brave and strong for coming here, and your family deserves you…

Dear mom: You are a wonderful mother…”

“There is a need for them to see other moms going through what they’re going through,” says psychiatrist Mary Kimmel, who runs the unit. She wears a denim jacket and black suede ankle boots, and whenever a patient asks if she’s a mom, too, she says yes, she had two kids.

She says everything here is tailored to the specific needs of new moms. Every room has a hospital-grade breast pump, there’s a lactation consultant who helps women with breastfeeding, and there’s a designated refrigerator for moms to store pumped milk.

The most distinctive feature about the program is the visitor policy. Most afternoons, the unit is bustling with husbands and kids.

“Babies can come to the unit and we really encourage that,” Kimmel says. “We encourage older kids to also come to the unit.”

Toddlers scurry around the day room during visiting hours, coloring, playing with toys, playing with each other. Women cradle their newborns, rocking them, feeding them.

The babies are not allowed to stay overnight though. There’s no nursery here like the units in Europe.

The main reason for that is the insurance companies.

Kimmel says no insurer in the U.S. would ever pay for a healthy baby to be admitted to the hospital.

“That baby doesn’t have a distinct need to be admitted and so it’s not possible to bill for that baby being at the hospital,” she says. And without that, the hospital can’t afford to run a nursery.

The unit is small — it has five beds — and women spend most of their time in the day room, a hospital lounge with a table and couch and a TV that’s usually tuned in to a home makeover show. The staff do what they can to make it feel homey here, less like a hospital, but there’s still a wall of glass around the nurses’ station, and patients have to knock on the window when they come to ask for something.

The days are very structured, with a range of treatments, all tailored specifically to pregnant women and new moms. There’s one-on-one therapy and lots of group classes: parenting and time management lessons, where women practice asking their partner for help. And a favorite among the moms: relaxation class.

“Get yourself as comfortable as you can, let your body relax,” murmurs recreational therapist Amber Koo over slow meditation music.

She puts on a special light machine that projects little stars onto the ceiling. That gives women a place to focus their mind, away from the negative thoughts coursing through their heads.

“Allow your breath to start going in your nose slowly,” Koo says.

For Alice Sarti, the moms unit at UNC was the first place that gave her hope as a new mom. After she had her son, she became engulfed by mania. She had dealt with depression many times before, but never this.

“Every minute I had to fill with a task: researching daycares, doing and re-doing my budget,” she says. “I’m not going to line up three bottles, I’m going to line up 17 bottles.”

She became an exaggerated version of herself. Super mom. She’s a business analyst and loves getting things done. She loved how productive she was. But then things started to spiral.

“There was a definite snap,” she says. “I started yelling about things that didn’t make sense. They made sense to me.”

It’s like the television show Homeland, when bipolar CIA agent Carrie Mathison sets up a situation room. She covers the walls with news articles and photos of the terrorists she’s chasing. She criss-crosses yellow string in all directions to illustrate the connections she sees.

It was like that in Alice’s mind.

“There was a logical chain there in my head, but externally those links were so far apart,” she says.

To her family, it was just an incoherent rage. They called the police and they took Alice to the nearest hospital that had an available bed, in this case, not the mom’s unit at UNC, but rather a general psych ward.

“You saw people that couldn’t speak, that could barely walk. People that were discharged in that condition,” she says.

Alice didn’t want to be drugged like that. She refused to take any meds, and that made her unpopular with the staff.

“I did have a social worker tell me I was going to lose my child if I didn’t ‘pull it together,’” she says.

During her three-week stay, she saw her son once, for 20 minutes.

“I was not able to touch him on any level. He was in his car seat and I reached for him and I was yelled at,” she says.

It’s hard for her to admit what it was like coming back to him, after she was discharged.

“It felt like a burden,” she says. “It felt like, ‘How am I ever going to do this?’ I held him, I bathed him, and I did all the things, but the connection was not there. I lost time with my son and I’m never going to get it back.”

Alice was not feeling better when she was sent home from that hospital. She ended up in another hospital, and discharged again, her mania still boiling. She eventually ended up at the mom’s psych unit at UNC Chapel Hill.

Finally, everyone seemed to understand what she was going through, the pressure she was feeling, the guilt. She saw her son regularly, and staff helped her start to re-establish her bond with him.

“It was this incredibly nurturing environment,” she says. “It changed the trajectory of my life and my son’s life.”

But even at this seemingly perfect place, things go wrong. When Alice was discharged, her mania cleared. But then she slipped into the deepest, darkest depression she had ever known. She checked herself into UNC again, afraid she was going to kill herself.

With Alice, and other patients, doctors are under so much pressure to get moms home quickly, sometimes they overshoot on the medications, says Dr. Mary Kimmel, who runs the unit. Some of that pressure comes from the moms themselves, who want to be with their kids, but it also comes from the insurance companies.

UNC’s mom’s unit pays the bills like other hospitals – they take insurance to cover the costs of care.

But the longer a patient stays, the more an insurer has to pay, and that’s not good for their bottom line. Kimmel and other doctors say as soon as a patient comes off suicide watch, insurers start calling, asking when she can go home.

“Our average length of stay runs from about one week to two weeks,” Kimmel says.

In Europe?

“About 40 to 50 days is the average length of stay there,” she says.

That means doctors in the U.S. start patients on new drugs, but don’t have time to see if they work. Or, they have to start women on the most intense medications that force her to stop breastfeeding, instead of slower therapies that could extend the mother’s time to feed her infant breast milk.

It also means that patients like Alice can end up hospitalized four times before they get better.

Insurers insist the decision to discharge is not just about cost, but about what’s best for patients.

“We want to make sure that they’re getting the care that they need in the most appropriate setting,” says Kate Berry, senior vice president of Clinical Innovation for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a trade group for insurers.

Hospitals are not necessarily the ideal environment, she says, especially for making sure medications are stabilized.

“There are other settings where the care can continue,” she says, “such as a partial hospital or an intensive outpatient care setting that may be more supportive of having the mom and the baby together.”

Alice says mental hospitals in the US are just warehousing people. Only the mom’s unit felt like a place of healing, and despite the limitations of the system, it was the only thing that worked for her.

“It’s a different kind of place,” she says. “It’s the type of mental health care that everyone should have access to, not just mothers. That’s what mental health care in this country should look like, and it doesn’t come close.”

Right now, UNC is the only hospital in the country that has a designated psych unit just for pregnant women and new moms. A hospital in New York has a women’s only unit. And El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, where Dr. Dhami practices, will soon start construction on a women’s-only psych unit with a special focus on new moms. It’s slated to open in 2019.

Back in Silicon Valley

Two years after giving birth, Lisa Abramson plays catch with her daughter Lucy.

“Ready? Set? Go!” Lucy shouts, and Lisa rolls her a mini rubber soccer ball.

Lisa feels like she’s back to her normal self. But she’s been thinking a lot about her experience with postpartum psychosis.

Lisa is pregnant again.

“That was the most courageous moment of my life,” she says. “Without knowing anything of how this is really going to work out, ‘let’s try it again.’

She’s terrified, though, the psychosis will come back.

“It might still happen again. They say there’s about a 50 percent chance,” she says. “I can try to set up a more optimal situation, but you also just don’t know and it’s out of your control, which is hard.”

The number one thing she wants to avoid – is going back to the hospital.

“The hospitalization was probably the most traumatic of the whole experience,” Lisa says.

Her plan this time around is to make sure she’s getting enough sleep. She’s going to have a therapist and psychiatrist lined up if she needs medication. And if she can’t stand the tyranny of the breastfeeding schedule, she’s going to let it go. More than anything else, she’s giving herself permission to put herself first.

Part of the inspiration for this is…Oprah. Lisa’s been listening to the podcast Making Oprah, chronicling the history of the daytime talk show.

In it, Oprah talks about a show they were producing about where women put themselves on their “list.” She interviewed a life coach who had women draw up a list of all the people and things they needed to take care of. Then Oprah asked, where are you on that list?

Most of the women said, “I wasn’t on the list at all.” And if they were, they were last.

Lisa was shocked by what happened next.

“Then the coach said, ‘Okay, I want you to put you at the top of that list,’” Lisa says. “And the crowd booed. They booed her off the stage.”

That was 1992.

Lisa says, today in Silicon Valley, it doesn’t feel like much has changed. This is Ground Zero for women striving to have it all: high-stress career running a tech company, and two perfect kids. Women here think the over-achiever culture is one reason postpartum depression and anxiety rates are higher in California compared to the rest of the country.

Lisa says she still feels intense pressure to be the perfect mom.

“We’ve got so many messages of just self-sacrifice: Do anything for your kids, drop everything. That’s what it means to be a good mom and for me, that’s not what made me a good mom. That’s what made me fall apart,” she says. “I’m trying to put myself first, guilt-free, and know that that makes me a better mom.”

Lisa feels so strongly about this, she’s writing a book about it. It’s called the “Wise Mama Guide to Maternity Leave,” and it’s all about convincing Silicon Valley go-getters how to go easy on themselves when they have a baby.

She says throw out those ideas of fitting into your skinny jeans in a few weeks, pushing a cute stroller all put together. Shift your goals from giving a presentation to 100 people, to changing 15 diapers in a day.

“At Trader Joe’s, they say ‘Do you want help out to your car?’ Just say yes and practice feeling uncomfortable getting other people to really help you,” Lisa says.

Some Silicon Valley companies have asked Lisa to come talk to their female employees about how to not be so Type A about their maternity leave. She gives online courses, too.

“They’re like, ‘Oh I thought I could still get some stuff done, or I could tackle a project that I’ve been forgetting about during maternity leave.’ I’m like, ‘No, no,” she says.

It’s an interesting message from a woman who is herself cranking out a book while she’s pregnant. But then again, that’s the point. Finish everything well before the baby comes.

Lucy, is almost five now. Her second daughter, Vivian, is a year and a half.

The postpartum psychosis did not come again. With all the precautions Lisa took to protect her sleep, to ask for help, to put herself first, she warded off the helicopters and the snipers.

Lisa says she loves being a mom.