T

here’s a small, wood-shingled structure at Pond Farm near Guerneville — the former home, studio and school of renowned potter Marguerite Wildenhain — that’s so run-down, the insides are off-limits.

As I stand on the creaky exterior porch squinting through the grimy windows, I figure the ceramicist probably fired her pots in the cobwebby shack.

But it’s not Wildenhain’s kiln. It’s her house.

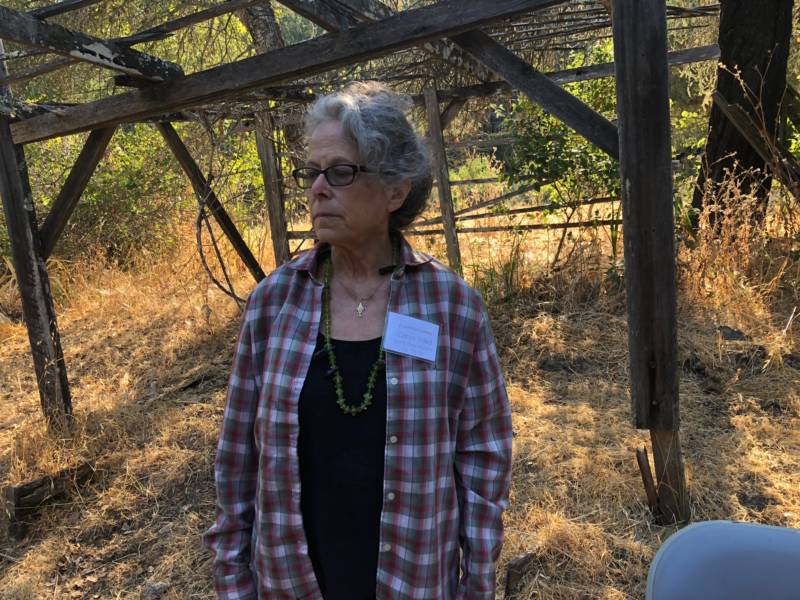

“This was her kitchen, her dining room and her bedroom,” said potter Caryn Fried, setting me straight. “This world-class artist lived this very humble existence right here.”

Once, people from all over the world traveled deep into the heart of the Sonoma County redwoods to study at Pond Farm with Wildenhain. She may not be a well-known name outside of the rarefied world of ceramic art. But an unlikely debate has arisen over the future of Pond Farm and Wildenhain’s legacy.

“She was just really a very powerful person,” said Fried, who studied with Wildenhain at Pond Farm in the 1970s, along with her husband. “The vibration that she put out.”

Lately Fried, as well as some other Wildenhain students and collectors, have been concerned about those vibrations; that they might grow weak or entirely disappear, now that plans are in motion to develop the bucolic and remote site where Wildenhain lived and worked for more than 40 years.

“If it becomes like this art center, you no longer have Marguerite’s energy there, which is what made Pond Farm,” Fried said.

“You have all these other people’s energy, which most likely is not going to be the energy that Marguerite had.”

Wildenhain came to Pond Farm in the early 1940s at the invitation of the landowner, Gordon Herr, who wanted to start an artist’s commune there.

Her dynamic, earthy ceramics could be found in high-end stores and museum collections. But the French-born artist’s story begins long before she first set eyes on the Sonoma Redwoods.

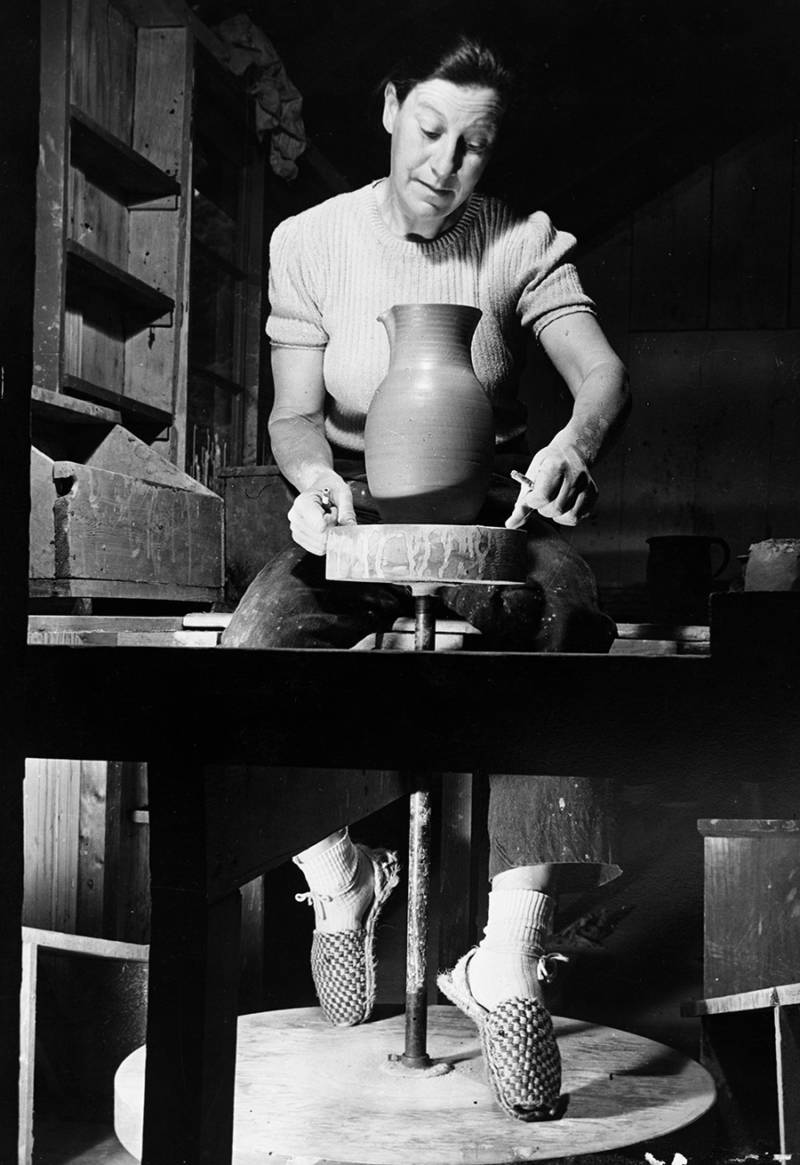

Wildenhain studied at the Bauhaus — the influential arts and crafts school that emerged in 1920s Germany. Her classmates included painters Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

She became Germany’s first female “Master Potter.” Then the Nazis came along. Wildenhain, who was Jewish, fled to New York, and eventually moved to the West Coast.

She was in demand as a teacher. Droves of students came to study pottery at Pond Farm, where Wildenhain taught them to think beyond the mechanics of throwing pots.

“I don’t admire technique as such,” she said in a documentary (see below) about her life and work shot at Pond Farm in the 1970s. “I admire if you have something to say with that technique: human, aesthetic, religious, or whatever you want to call it.”

Despite Wildenhain’s powerful legacy, Pond Farm fell into disrepair after her death in 1985 when she was 88.

In recent years, the nonprofit Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods has been working with California State Parks and other partners to resuscitate the site.

“We want to bring people to the site so there can be almost living history happening there again,” said Michele Luna, the Stewards’ executive director.