Illustrations by Joe Dworetzky

The sky above Ron Beeny turned black.

The 71-year-old was stuck in traffic as he evacuated from his home in Paradise on the morning of Nov. 8.

Trees and brush lined both sides of the two-lane road. In the darkness, Beeny had no idea where the fire was. A former firefighter, he knew that getting trapped between walls of fuel could be deadly.

“[When] daytime turns to night, the fire is burning extremely intense,” he said.

For more than an hour Beeny inched forward in his red Toyota pickup, heading west toward Chico. His home of 41 years was incinerated by the Camp Fire. The blaze that destroyed Beeny’s home is just the latest mega-fire in California — and the cost of fighting such fires has risen dramatically.

California dwarfs other states in fire-suppression costs, an analysis by a Stanford journalism class has found. The Stanford class analyzed daily reports from the most expensive fires in every state from 2014 to 2017, and found that dense development at the border of wildlands — in communities like Paradise, Cobb, and Santa Rosa — helps explain California fires’ exceptional damage and expense to put out.

A 2015 federal audit showed that fire suppression costs vastly more in these transition zones between wild and developed areas — Wildland Urban Interface areas, or WUIs, for short.

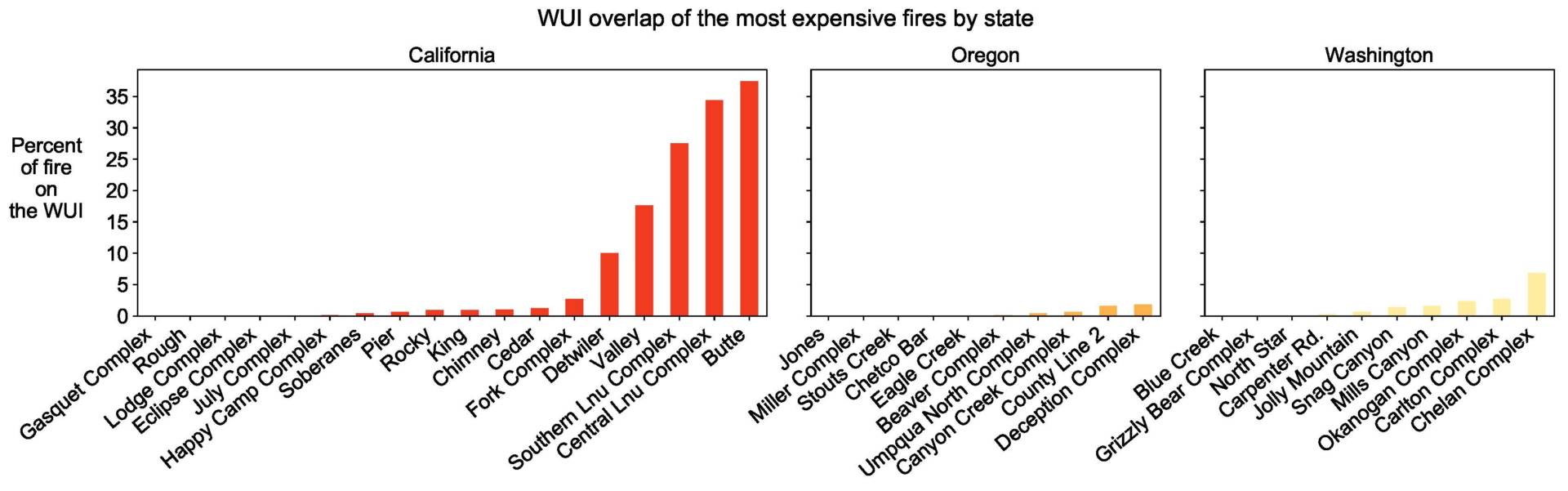

The Stanford analysis of fire costs found that, among the states that spend the most on suppression, California fires overlapped far more with the WUI: More than 30 percent of the 2015 Butte Fire, for example, burned on WUI lands, destroying almost 1,000 buildings. Much of the state’s WUI is made up of chaparral — dry shrubland — that burns fast and hot.

Policymakers differ on how state and local governments should intervene. But experts like Tom Harbour — who served as National Director of Fire and Aviation Management before retiring from the U.S. Forest Service in 2016 — agree that the growth of WUI has fueled a crisis.

“You’ve taken a lot of land in [California] … that used to be ponderosa pine down near the bottoms of these drainages … and now you put homes in there,” Harbour said. “Well, the pine trees are still there. The bitterbrush is still there. The sagebrush is still there. The desire that Mother Nature has to burn is still there. But now your home is there.”

High costs, high damage

Ron Beeny’s home was one of more than 13,000 destroyed in Paradise. One month after the Camp Fire began, the death toll stood at 86, with three people still missing.

Officials are worried about another tally, too: the ballooning cost of putting out such fires.

A strong economy and a state budget surplus mean that recent firefighting costs will not cut into other priorities this year, said California Assembly Budget Committee Chair Phil Ting, D-San Francisco. But Ting and other lawmakers are looking for ways to curb the destruction long-term.

“It’s a major concern,” Ting said. “We’ve had these two horrific wildfires up and down the state, two really bad summers, so we need to do whatever’s possible to help.”

By the end of August, California had burned through most of the $440 million in emergency funds that had been allotted for the 2018 fiscal year. One week later, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) requested an additional $234 million for firefighting efforts through November.

It was a prescient request — but insufficient. November’s Camp Fire alone would cost more than $150 million to suppress. Late last month, Cal Fire asked for about $250 million more in emergency funds.

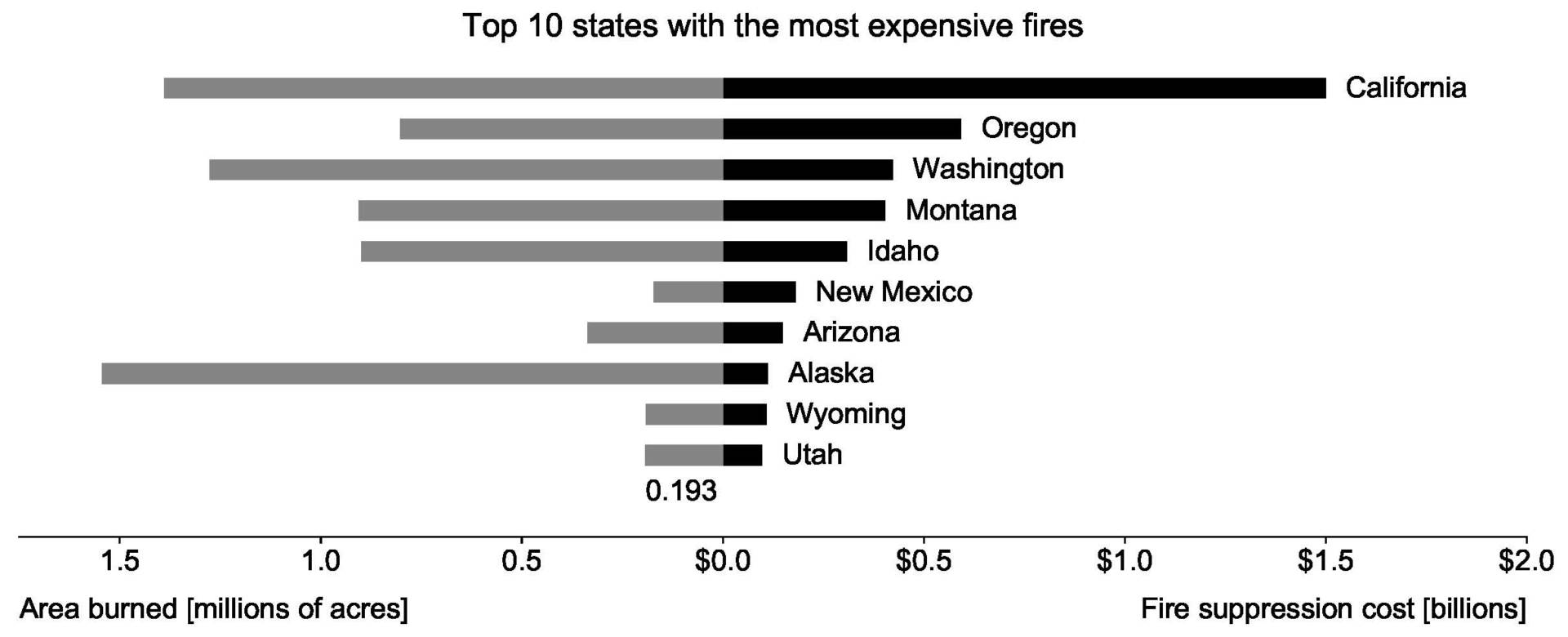

Daily reports tracking estimated suppression costs show that the 20 most expensive fires in California from 2014 to 2017 cost nearly $1.5 billion to fight.

That’s more than double the cost of fire suppression for the 20 most expensive fires in Oregon, the state with the next highest price tag, and more than triple that of third-ranked Washington’s top fires. And the daily reports aren’t even complete– reports are missing for the Thomas Fire, California’s costliest fire in 2017.

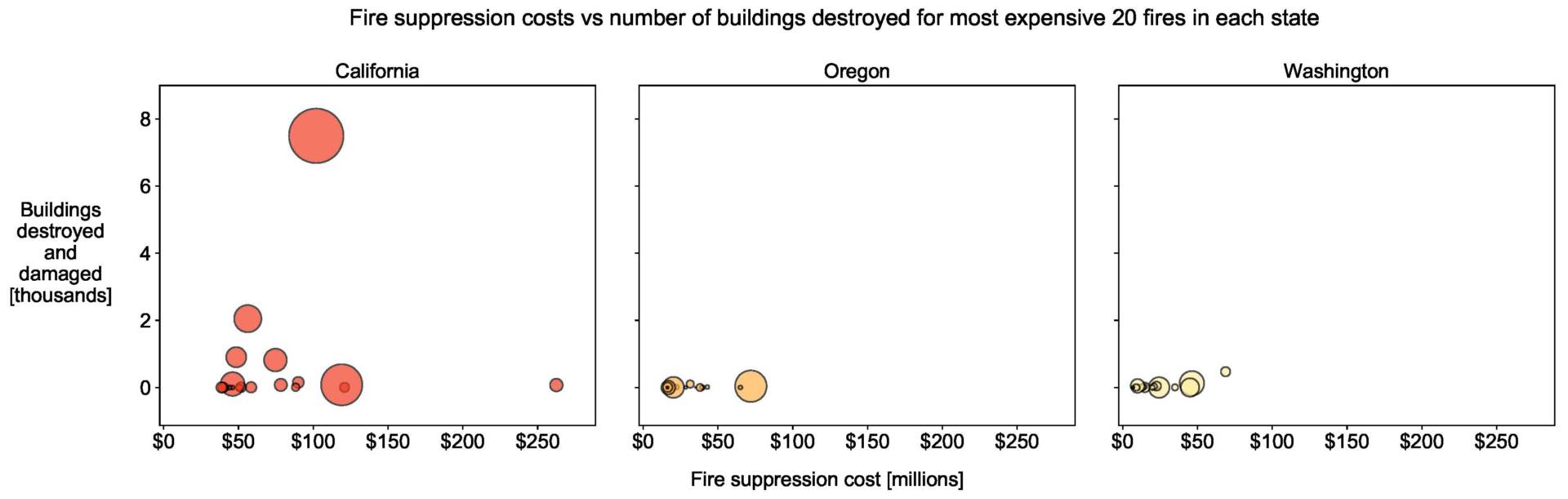

The most expensive fires to fight are not necessarily the largest. The state’s unusually high suppression costs coincide with a second measure where California leaves other states far behind: damage to buildings.

From 2014 to 2017, California’s most expensive fires destroyed and damaged over 60 times more buildings than Oregon’s priciest fires did, and over 10 times more buildings than Washington’s fires.

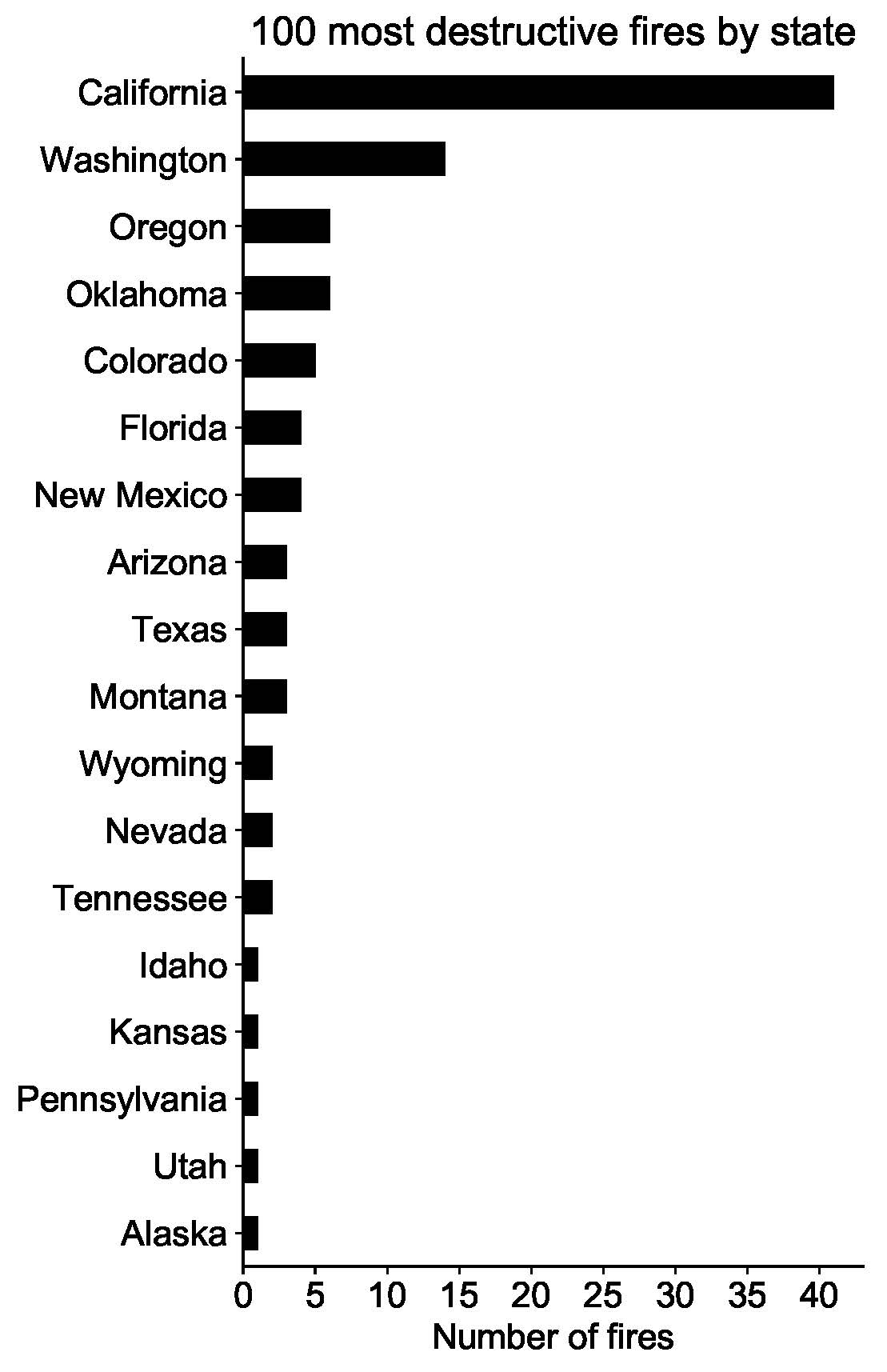

By the measure of buildings destroyed, 41 of the 100 most destructive fires in the nation from 2014 to 2017 occurred in California.

Source: Incident Status Summary and Situation Report data, National Wildfire Coordinating Group ( Irena Fischer-Hwang/Stanford Big Local News/Bay City News)

At the edge of wildland and towns

In 2015, the Butte Fire spread rapidly toward old Gold Rush towns in the Sierra foothills of California’s Amador and Calaveras counties, fueled by chaparral shrubbery dried out in the summer heat.

By the second day of the fire, more than 6,000 buildings were at risk; by the fourth, 81 houses had been charred. More than 4,000 people joined the firefighting effort as agencies worked to contain the fire, protect homes and evacuate hundreds of people all at once.

“Suppression efforts had minimal impacts on perimeter control due to a high focus on structure defense,” read the second of the Butte firefighters’ Incident Status Summary reports, which detail fire conditions and resources in use at a given time.

Over a third of the Butte Fire burned in the WUI. By contrast, none of Washington’s most expensive fires had more than 7 percent of their area overlap with WUI zones.

None of Oregon’s most expensive fires overlapped more than 2 percent with the WUI in terms of area. An analysis of geospatial data shows that 18 of California’s 20 most expensive recent wildfires overlapped with WUI areas, while in Oregon and Washington, fewer than half did.

Fires that threaten buildings are “always going to be more costly,” said Rocky Opliger, a deputy chief for the La Verne Fire Department in Southern California who led Forest Service suppression efforts on major fires as an incident commander. “It costs more money when you’re bringing in more expensive resources.”

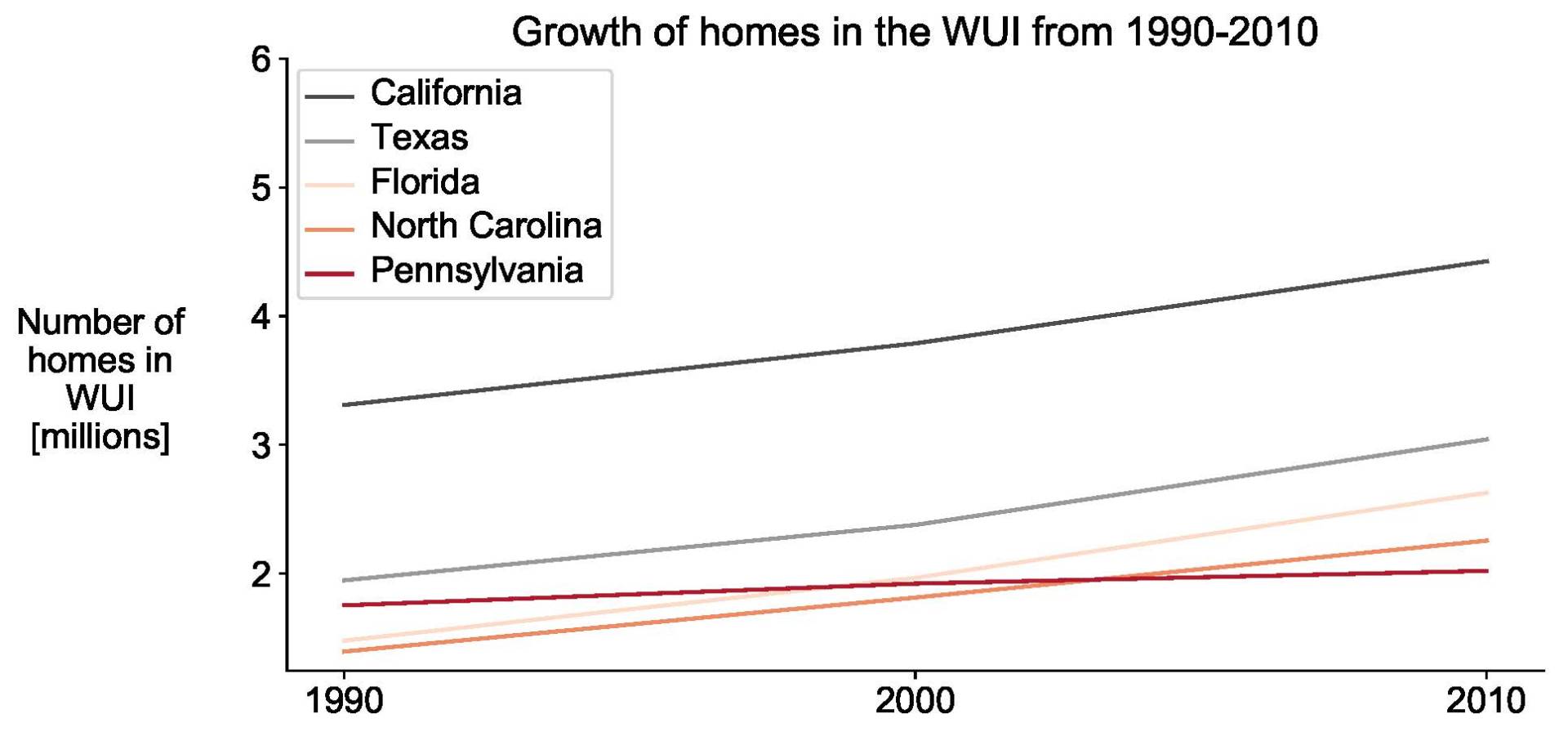

In 1990, California had more than 3 million homes in the WUI, according to Forest Service data. By 2010, that number had ballooned by more than a third to over 4 million — 50 percent more than Texas, the state with the next largest number of WUI homes.

California had one of the highest building densities in WUI areas in the country in 2010, the latest year for which the Forest Service has data.

And people continue to move into the WUI. In El Dorado County, for example, the foothill town of Placerville has sprawled toward a national forest, said Scott Vail, former deputy chief for fire administration with the California Office of Emergency Services.

In the 1970s, Vail said, it “took forever” to get into Placerville from the forest. “Now, once you get out of the national forest, the city starts.”

California’s WUI is especially fire-prone, and that stacks the odds against developed WUI areas, said Michael Mann, a George Washington University geographer who has studied the overlap of California’s WUI with high fire-hazard zones.

Chaparral, for instance, evolved with frequent wildfires and feeds fires so intense that they burn all the vegetation in their path.

These areas become even more likely to ignite when people arrive, said Char Miller, a professor of environmental analysis and history at Pomona College.

“When we move into these landscapes, we burn them,” Miller said.

Cost of fighting fires in the WUI

Fighting fires in the WUI costs $1,695 per acre, according to a 2015 Forest Service audit that examined several WUI fires from 2008 to 2010.

That’s more than twice the cost of putting out fires in a forest, and nearly 30 times the cost of fighting fire in undeveloped grassland or shrubbery.

When people and their homes are threatened, agencies tend to marshal whatever resources are needed, said Opliger, the former Forest Service incident commander.

“I have yet to have an agency administrator really restrict me on what I need to do as far as getting the job done, especially when it involves direct protection of civilians, private and public property,” he said.

Fighting fires becomes far more complex when firefighters are protecting populated areas, said George Huang, a San Luis Obispo battalion chief.

“It’s like a huge chess game,” Huang said. “We have fire engines … trying to put out the fire … a couple engines at homes to make sure that homes don’t catch on fire, and at the same time we’re working with the law enforcement to evacuate people out of their homes.”

Development in rural areas also makes fire prevention tactics such as prescribed burns harder to carry out, said Tom Harbour, the former Forest Service official. The controlled burns produce smoke that can upset residents.

“I don’t like that,” Harbour said of the smoke produced. “You don’t like it. The American public doesn’t like it.”

Limiting the damage

Legislation passed in September takes some steps toward limiting damage from fires within the WUI. While California Senate Bill 901 focused primarily on forest management and the liabilities of utilities, the measure also puts “a little bit more teeth” into community planning guidelines for fire-prone areas, said Cal Fire researcher Dave Sapsis.

Starting in 2021, local governments in areas with very high chances of fire will have to take more precautions previously required only for state lands — for example, ensuring that roads are wide enough for evacuation.

But some experts doubt SB 901’s changes will be enough to prevent the kind of widespread destruction the state has experienced in the WUI.

Miller believes one solution is for communities to establish programs, funded through municipal bonds, to buy up wild borderlands from willing private owners and limit development within them.

But local governments have had little financial incentive to prevent development: turning away new residents reduces their tax revenue, while state and federal agencies tend to bear the costs of wildfire suppression, said Kimiko Barrett, a researcher at Montana-based think tank Headwaters Economics who has studied WUI and fire risk.

“It’s what we call a moral hazard … [Cities are] able to approve certain decision-making processes without having to pay the consequences of those decisions,” Barrett said.

State legislators have been reluctant to intervene in planning issues they consider the province of local governments, but some policymakers are exploring further statewide legislation.

Assemblyman Chris Holden, D-Pasadena, who co-chaired the development of SB 901, may introduce new legislation early in 2019, according to his spokesman Garo Manjikian.

Meanwhile, legislation passed in 2018 authorized the California Department of Insurance to create a “working group” to investigate potential market-based solutions to curb development in fire-prone rural areas. Yet no timetable has been established for their work.

The glacial pace of legislative action leaves experts frustrated. On Nov. 29, University of California at Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment (CLEE) and the nonprofit Resources Legacy Fund released their joint recommendations for incoming Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Included was a proposal to create a wildfire-focused leadership position within the governor’s office. The appointee would be charged with “developing and implementing state incentives for local governments to limit new development in high-risk areas.”

“I think the state needs to play a stepped up role coordinating all the different agencies involved, trying to marshal the funding to do it, and then also trying to change local government land use decision-making,” said Ethan Elkind, director of CLEE’s climate program.

Even those knowledgeable about fires find it difficult to resist the call of the wildlands. Ron Beeny, the firefighter who escaped last month’s Camp Fire, said he liked Paradise precisely because of its natural beauty.

“We just like the mountains. We like the trees,” he said.

For most of his career Beeny was an engineer, driving a fire engine to fires of all kinds. He was frequently a first responder, fighting hundreds of fires over many years.

But on the morning the Camp Fire blazed into Paradise, his emergency plan was the same as everyone else’s: “Get the hell out.”

At first, Beeny thought he would rebuild his home in Paradise, but his son is encouraging him to settle elsewhere.

He’s not sure yet where he will land — Oregon is at the top of his list. But wherever he ends up, he will probably live in the WUI.

“I know how ridiculous it sounds,” he said. “But that’s the kind of country we like.”

Story by Joe Dworetzky, Irena Fischer-Hwang, Jay Harris, Hannah Knowles and Emily Surgent

This story comes from a Stanford University class affiliated with the Big Local News project. Journalists collected, processed and analyzed data on the cost of wildfires across California and the U.S. to produce this report. The underlying data and analysis will be released along with how-to guides for other journalists and researchers evaluating the impact of fires. Big Local News is a Stanford Journalism and Democracy Initiative (JDI). Its goal is to collect, process and share governmental data that are hard to obtain and difficult to analyze; partner with local and national newsrooms on investigative projects across a range of topics; and make it easy to teach best practices for finding stories within the data.