A 12-year-old named Gisbelle, one of the 25 kids at the shelter, said it's tough to get her homework done here.

“I don't have internet here except for my mom's hot spot,” she said. “And when it comes to typing homework, I can't finish, because the bedtime is around 9 p.m. and I don't finish at that time.”

Gisbelle’s 10-year-old sister, Sahily, is sitting nearby listening, and eating a cup of noodles. She wears a T-shirt that's a bit dirty, a little too small. School has been hard, she said.

“I can’t concentrate real good to get all my work done," she said. "My mom tells me it’s going to be OK. Sometimes I feel it’s not going to be OK.”

'They're like me'

Teachers at Sherwood Elementary School in Salinas are seeing firsthand the effect this is having on their students, about half of whom are considered homeless.

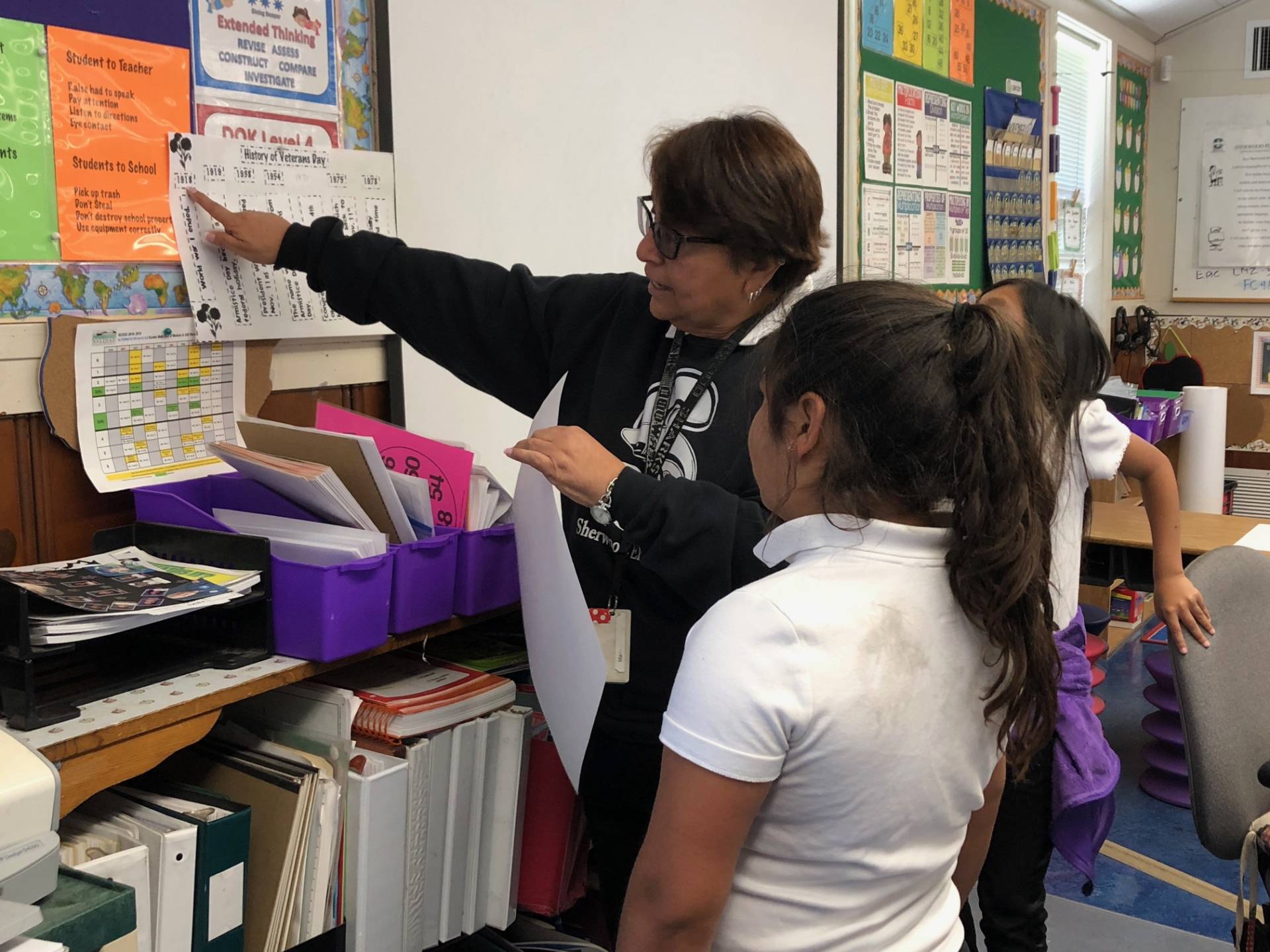

This year, 21 of the 25 students in the third-grade class Maria Castellanoz teaches are considered homeless. Some are on the streets or in shelters, but most are living in trailers and garages, or renting rooms, closets and even hallways.

“They fall behind,” said Castellanoz, who's been teaching here for 20 years. “They don't have computers. They don't have the internet. They don’t have a desk to sit at. That would be a luxury, let alone a kitchen table, because people are using that kitchen table.”

Oscar Ramos, a veteran second-grade teacher, said 70 percent of his students are considered homeless. “Some of them come in hungry, some of them come in very sleepy," he said. "You see the frustration in their face because they don't have everything they need to enjoy the day."

These factors make teaching challenging. But Castellanoz and Ramos, who both grew up in poverty, said they feel a strong personal connection to their students.

“The children that are here, they're like me,” Castellanoz said. "My dad worked in the fields. We lived in a labor camp till I was 11 years old.”

Ramos and Castellanoz made it out of poverty. They went to college, they do work they love, and they want the same thing for their students.

“Somebody has to be here with these kids and say ‘You know what, you can do it,’ ” Castellanoz said. “To tell the parents, ‘I did it, so your child can do it.' "