For 12 years, California’s juvenile justice facilities were overseen by a court monitor — the result of a lawsuit aimed at ending the culture of violence, including staff abuse and frequent suicides, at the state’s correctional institutions.

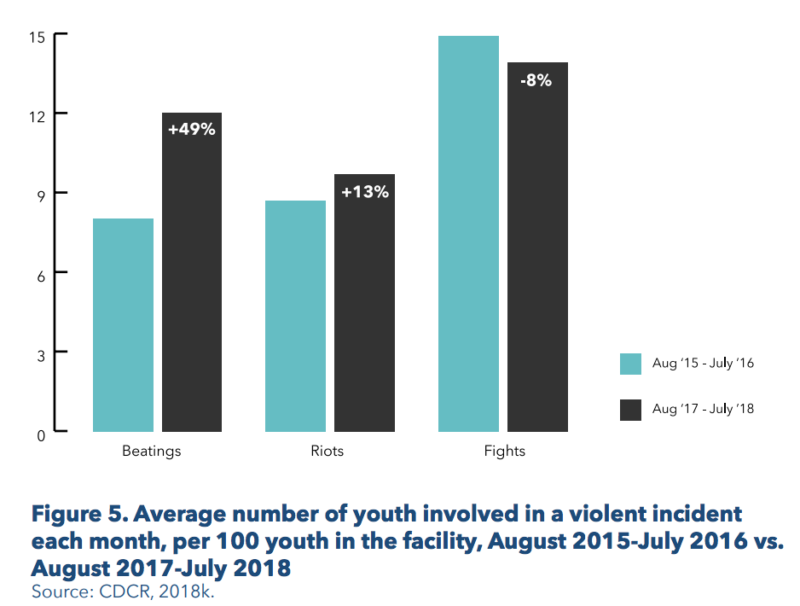

But now, three years after that oversight ended — and despite assurances “that the state was entering a new era of rehabilitative treatment” — a new report finds the 600 young men and women housed in the four Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) facilities in California are still being exposed to “violent” and “inhumane” conditions, where fights and riots are a part of daily life and lead to lasting trauma.

The 102-page report from the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice concludes that this culture is “concealed by an absence of state oversight,” as well as the isolated locations of the facilities, compared to where the youths’ families live.

“In the three years since court monitoring ended, DJJ has returned to its historical state of poor conditions, a punitive staff culture and inescapable violence,” says the report.

The state is also spending an exorbitant amount of money — about $300,000 per kid annually — to run these institutions, which housed 10,000 young people 20 years ago, but now are drastically under capacity. The majority of DJJ youths are 17- to 19-year-olds with assault or robbery convictions.

Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice staff members Maureen Washburn and Renee Menart wrote the report after touring several DJJ facilities and speaking to dozens of people involved in the juvenile justice system, including facilities staff and young people who are currently incarcerated or formerly served time inside DJJ institutions.

Menart said that when you walk into a DJJ facility, it feels like a prison, and that every youth they spoke with had either witnessed or experienced violence. This experience continues to haunt them when they leave DJJ, she said, which contributes to high recidivism rates.

“Among the youth we spoke to, you have them all describing feeling very isolated when they come home — feeling distant from their families, feeling overwhelmed by the world,” she said. “These youth are coming out of institutions where they spend prime years of their adolescence. They come in as teenagers and they come out as an adult.”

Washburn said she was struck during their tours by the secretive culture at DJJ — including limits on which youths they were allowed to talk with.