In late March, a criminal investigator from California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) and an inspector from Santa Clara County’s Environmental Health Department conducted a surprise inspection of the Target Masters West gun range in Milpitas. Their principal objective was to discover whether lead from the range could pose a threat to children next door at the Sweet’s Gymnastics youth training center. The inspection was triggered by information shared by Capital and Main with DTSC.

County Temporarily Closes Milpitas Gun Range and Neighboring Kids’ Gym After Detection of Lead Dust

Our investigation has revealed that lead from the gun range contaminated the inside of the gymnastics center. The county health department closed the youth facility Friday until further notice. And the sensitive process of figuring out if vulnerable children have been poisoned from lead exposure is underway.

Ongoing warnings, little action

Besides uncovering evidence of potential lead contamination at the site, a public records search reveals that state health officials may have ignored more than two decades’ worth of warnings about the gun range. Officials may also have helped the owner of the gun range owner avoid closely monitoring his employees’ blood-lead levels.

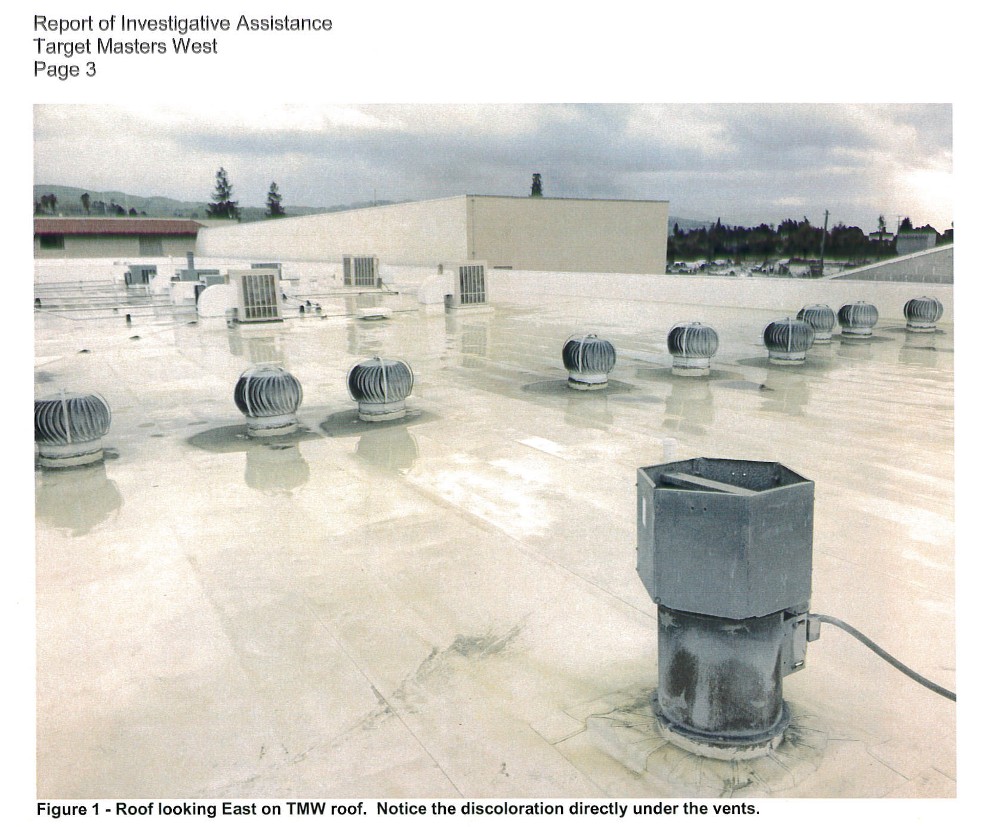

The investigators’ resulting report states that “the roof has obvious signs of lead dust accumulation in and around the turbine vents evidenced by gray matter and staining and supported by lead readings taken in these areas.” The DTSC report also states that the agency considers levels of lead dust greater than 1,000 parts per million as “hazardous.” (The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and other federal agencies have more stringent standards.)

Lead is a powerful neurotoxin, especially in toddlers, and can cause permanent developmental delay. Target Masters’ lead levels were almost entirely above the safety threshold and ranged as high as 52,000 ppm.

The DTSC took further readings at the front door of the gymnastics center and at a roll-up door. Those readings were 1,340 and 2,676 ppm, respectively.

UC Davis researcher Peter Green, who specializes in urban lead contamination said via email that, out of an abundance of caution, kids who have recently attended the gymnastics center should be tested to see if they have been exposed to lead. “Dust, including lead (Pb) dust, can travel many yards — even in a light breeze,” he said in an email. “The high-Pb dust from the nearby emissions concern me greatly.”

After Capital & Main informed Santa Clara County of the third-party test results and conveyed Green’s concerns, the county’s public health department, along with CDPH’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, took lead tests on May 1 inside the gymnastics center and gun range. Two days later, the county announced it was closing both businesses effective immediately because, according to an announcement, the test results “indicate an elevated risk of lead exposure for people inside the buildings, and the County immediately took action to close the businesses to the public.”

Santa Clara County officials did not explain why it took them 38 days to address the danger to children after the March 27 inspection determined that “the gun range is not maintained or operated in a manner to minimize the possibility of a release of lead to the air, soil or surface water.” That inspection report singled out a “passive exhaust ventilation system” in which air is moved by swamp coolers and exits the roof without any kind of modern filtration system.

In an interview last week, prior to the closures, Target Masters’ owner Bill Heskett acknowledged that for decades his gun range lacked the type of filtration system needed to prevent lead dust from escaping the building.

“There’s not much I can say about yesterday,” Heskett said. “I’m addressing the problem now.”

Heskett dismissed concerns about children who attend the neighboring gymnastics center as overblown, characterizing the issue as part of an ongoing “attack in California on anything to do with the firearms industry.”

Lack of enforcement

The two agencies most responsible for ensuring that workers are not subjected to dangerous levels of lead at gun ranges and other workplaces are the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and the state’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (Cal/OSHA). The CDPH has its own internal division that tracks blood-lead levels, but has no enforcement powers. To take remedial action, it must refer cases to Cal/OSHA, which has the authority to inspect and, if necessary, close down contaminated sites. Capital & Main’s ongoing investigation into lead contamination in California has found that CDPH rarely refers cases to Cal/OSHA.

For decades, CDPH was aware of serious problems at Target Masters West. As far back as 1996, a whistleblower had raised the alarm about the range’s air-filtration system, and internal CDPH emails discussing the range show the agency was warned by a severely lead-poisoned worker that “environmental pollution [is] happening as a result of improper ventilation.” Although the neighboring gymnastics center is not mentioned by name, CDPH officials discussed “getting [redacted word] kids tested.”

Dangerously high blood-lead levels

Over the years, CDPH has sent more than a half-dozen letters to Target Masters West, informing the gun range that another worker’s blood-lead levels were found to be dangerously high. A 2006 letter, for example, states that a worker’s blood-lead levels indicated “serious problems with your lead safety program that should be corrected. They may also indicate violations of the Cal/OSHA lead standard.”

Although the Cal/OSHA warning was underlined in the letter, CDPH never referred the range to Cal/OSHA for further action. In 2011, Target Masters again received a letter from CDPH. Heskett contacted CDPH directly and claimed that “the ventilation system was good.”

“Reports of elevated blood-lead levels should lead immediately to an inspection to ensure that the employer abates the hazard as quickly as possible, in order to prevent additional lead poisoning cases,” said David Michaels, who served as assistant secretary at the federal OSHA from 2009 to 2017. “In some cases, children may be exposed, either through their presence at or near the gun range, or from lead dust being taken home on workers’ clothing.”

At least 38 states follow the federal standards that Michaels helped implement, but California is not among them.

Eventually, in 2016, CDPH did intervene — on behalf of Heskett. At the time, Veronica Perez, a medical assistant at a local occupational health clinic, raised concerns about a patient who worked at Target Masters and repeatedly showed elevated lead levels. If Cal/OSHA had received a referral from the clinic, the agency would almost certainly require the type of expensive changes to the lead-spewing ventilation system that it would later order in 2019. Heskett acknowledged that he instructed the manager of the gun range to contact CDPH to try and convince the clinic that the case did not warrant a referral.

Heskett still claims he asked CDPH to intervene in 2016 from a personal belief that Santa Clara County was intent on dissuading young people from working at his gun range.

The CDPH official who took the initial phone call from Target Masters summarized the gun range’s concern in an email: “They think [Perez] is wanting to take too stringent actions.”

The issue was forwarded to the Occupational Lead Poisoning Protection Program (OLPPP), the CDPH division that monitors adult blood-lead levels.

The relayed message from Target Masters spawned more than a dozen internal emails within OLPPP, creating the impression of a back-channel effort to circumvent a Cal/OSHA referral. One email sent by Susan Payne, a chief case investigator for OLPPP, stated, “This issue has come up a few times. Most of the [redacted word] are satisfied once learning that OLPPP handles all things occupational. … For the ones who refuse to accept this (has only happened a couple or a few times, I think) we get some kind of doc to doc discussion going.”

Perez said a CDPH official informed her that the Target Masters employee’s elevated lead levels did not represent a “serious adult case.” She said that the impression that she was about to refer Target Masters to Cal/OSHA was likely a misunderstanding. After speaking with Perez, CDPH’s Payne wrote that the clinic had “confirmed they have NOT made a Cal/OSHA complaint.”

CDPH declined to comment about the actions it took in 2016, at the request of Target Masters, beyond saying that “CDPH cannot provide any further details” for reasons the department said would “violate the privacy of an employee.”

Hours before the May 3 closure announcement, CDPH responded to questions that Capital & Main had posed weeks earlier. In its statement CDPH confirmed that it does “not currently refer employers to Cal/OSHA for enforcement action based solely on an employee blood lead level (BLL).”

In March, the director of the 3,000-plus employee department, Dr. Karen Smith, struck a different tone when she sat down with Capital & Main for an extensive background conversation. She acknowledged structural issues with the way that OLPPP shares elevated blood-lead results with Cal/OSHA.

But a California lawmaker who has been pushing to change the way CDPH handles lead poisoning cases among workers said that more than vague promises are needed.

“How many more people will have to succumb to the debilitating effects of lead exposure before we decide to change this failed system?” asked Assemblymember Ash Kalra, D-San Jose, who is sponsoring legislation to strengthen worksite safeguards against lead poisoning. “Worker safety should be paramount, not just to businesses, but also to the agencies tasked with protecting these workers.”

Dave Sweet, who owns the temporarily shuttered gymnastics center, said he was “shocked” to learn that “all this drama has been going on next door having to do with lead-poisoned workers.

“I have been kept completely in the dark,” he said. “That’s just not right. What’s vital now is that this gets fixed, and fast.”

The original version of this story was published on Capital and Main on May 4.