The man accused of killing a woman and injuring three people in a shooting at a Poway synagogue in late April is expected to appear in court this week to face more than 100 federal charges, including obstruction of the free exercise of religion and hate crimes.

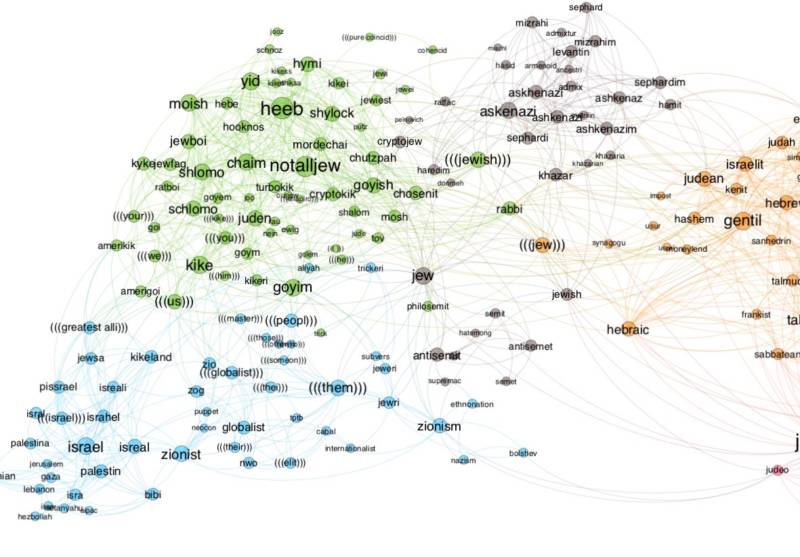

John T. Earnest, 19, allegedly acted alone, but he posted an anti-Semitic “open letter” on 8chan, in which he credited the online forum famous for anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for helping to shape his views. He also expressed the hope his actions would serve as inspiration for a new set of memes to spread these ideas.

Conspiracy theories have been at the core of anti-Semitism, and the internet is a fertile breeding ground for conspiracy theorists. Exactly how this genre is evolving was the subject of an event held last week at the Computer Science Museum in Mountain View by UC Santa Cruz’s Data and Democracy initiative.

“Anti-Semitism is one of the oldest hatreds in the world,” said Rachel Deblinger, co-director of the Digital Jewish Studies Initiative and director of the Digital Scholarship Commons at UC Santa Cruz. “The internet provides the tools of creation and dissemination to everyone.”

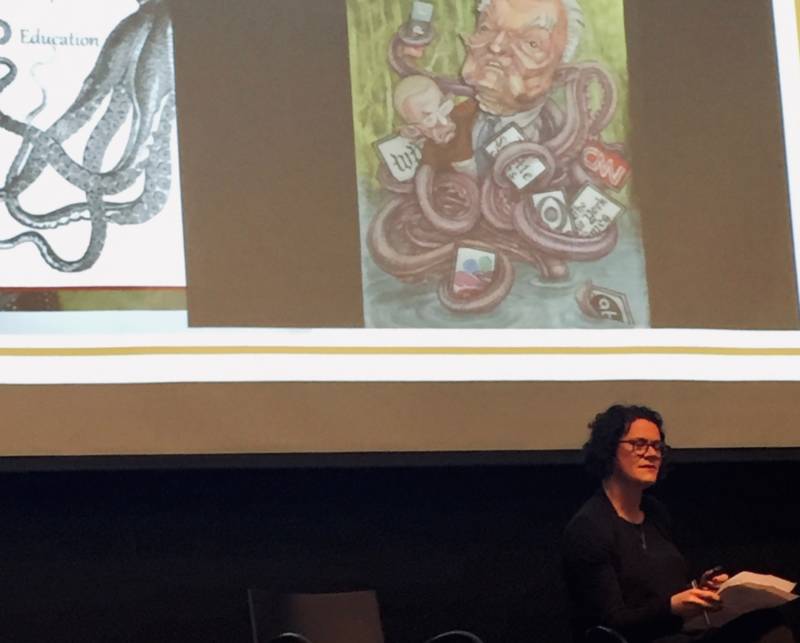

She argues, as do others, that social media platforms of all kinds are effectively resurrecting and refreshing ideas and visual tropes — or “memes” — stemming back to Medieval Europe.

You can see modern versions of images used to demonize Jews all over social media and not just on forums where you might expect to find openly, virulent anti-Semitism, like 4chan, 8chan and Gab.