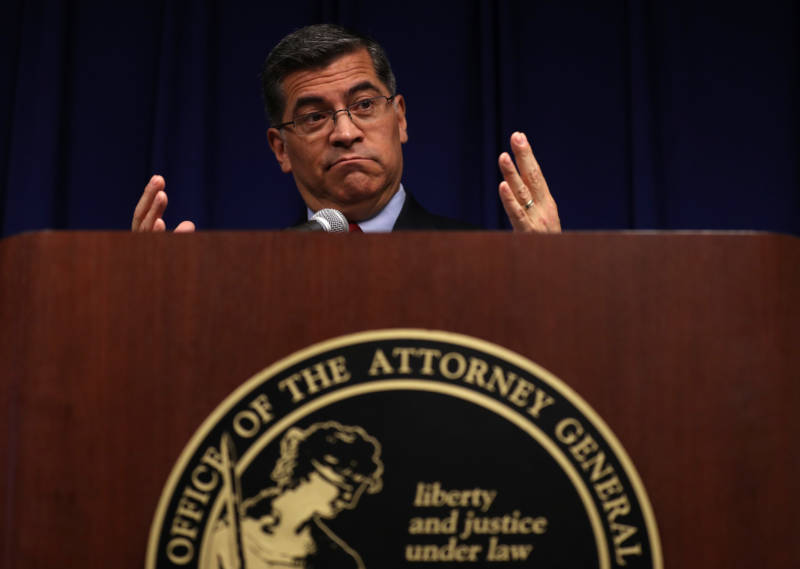

In addition to questioning SB 1421’s application to older records, the attorney general has argued that he shouldn’t have to turn over files about local police and sheriff’s departments, but should only be obligated to provide information about state agents.

To support that argument, Senior Assistant Attorney General Michael Newman wrote that an example case from a local law enforcement agency “includes over 109,000 items stored in an electronic database, including text messages, emails, documents, photographs and audio or video files,” that would all need to be reviewed and redacted before being made public.

In its written statement Friday afternoon, the Department of Justice maintained that it does not plan to release the files it has from local law enforcement agencies.

Ulmer said that Newman’s declaration was “terse and conclusory.” He said the new law clearly requires the Department of Justice to turn over any records it maintains, regardless of who created them.

“What this sounds like to me is you don’t want to do the work at the Attorney General’s Office,” Ulmer said, adding that he understands the position “because it’s going to be onerous.”

But he added that the issue is bigger than First Amendment and news organizations pursuing the records with the help of “high-powered lawyers.”

“It’s mothers and fathers of people shot by the police,” he said, underscoring the public interest in the long-secret information.

Attorney Thomas Burke, who represents KQED in the case, said Becerra’s position has led many police departments and sheriffs to withhold their own files. He said that should stop after Friday’s ruling.

“This is an important victory for access to police misconduct records because it requires the attorney general to now act,” Burke said after the hearing.