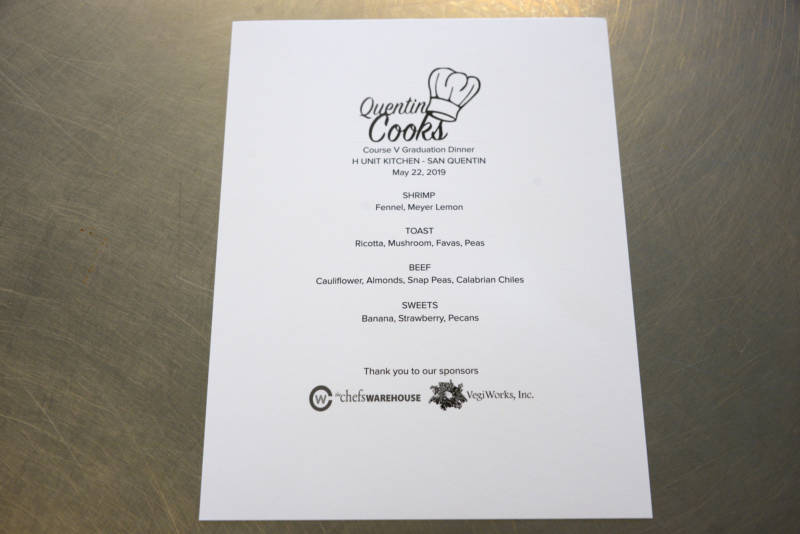

It’s a special menu tonight at San Quentin State Prison: beef short ribs with a cauliflower, snap pea, almond and Calabrian chili pepper side, ricotta and vegetables on toast, and shrimp on skewers, seasoned with cayenne pepper, paprika, lemon and fresh fennel foraged from local hills.

San Quentin Cooking Class Serves Up Chance for Better Future After Release

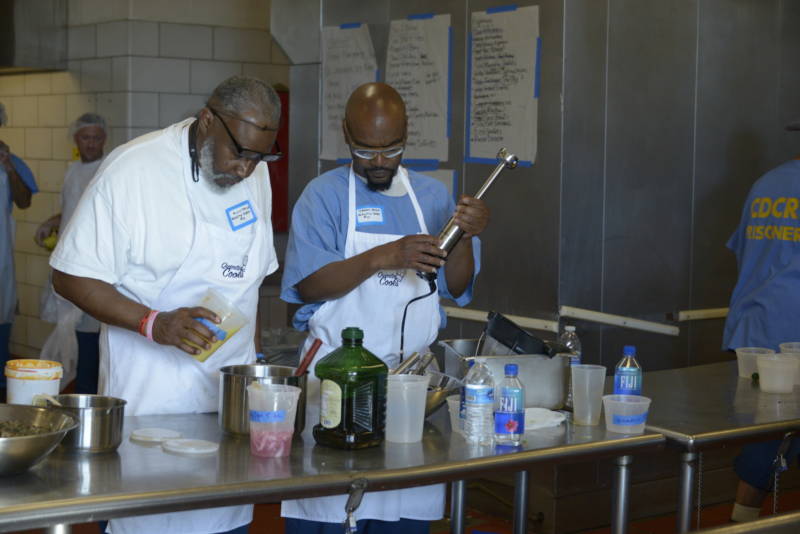

The meal is made by inmates graduating from the Quentin Cooks program, and one of them, Kerry Rudd, is standing behind an industrial kitchen cooktop sizzling with rows of grilling toast. Wearing his Quentin Cooks chef’s jacket for the first time, Rudd is smiling and shouting over the crackling bread and the nervous, excited hum of his classmates taking preparation orders.

“We just graduated, so it’s a happy feeling,” Rudd said. “It’s been a bonding experience. It’s even weirder that it’s happening in prison because you think … it’s prison, like really tough and macho. But we’re having a good time here making food and getting close to each other.”

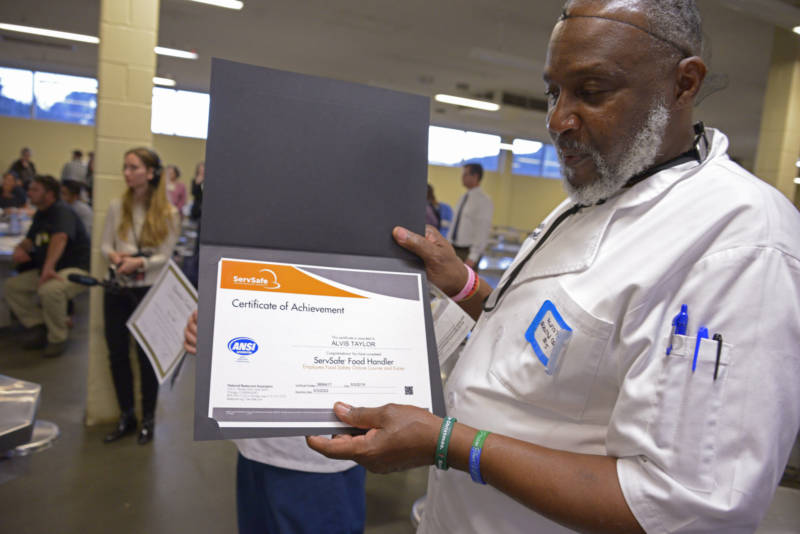

Rudd and his classmates are the fifth group to graduate from Quentin Cooks, a culinary program offered at San Quentin since 2016 that serves men in the prison’s H-Unit. The men in H-Unit have sentences of a fixed length, meaning they have a clear idea of when they will be released and looking for a job. The program’s leaders try to select men who will be out within a year or two so that the three-year ServSafe Food Handler certificate that they earn in the course will still be valid. The idea is that this credential will give them a leg up in finding employment right out of prison.

In lieu of a regular graduation ceremony, the graduates are preparing this feast for supporters, restaurant owners and food industry leaders — some of whom might be potential employers — and Quentin Cooks alumni who have been released. The dinner is the culmination of four months of culinary training under instructors Huw Thornton and Adelaar Rogers, and guest chefs like Cal Peternell, formerly of Chez Panisse.

Red Tape & Elbow Grease

Quentin Cooks is the brainchild of Helaine “Lainy” Melnitzer and Lisa Dombroski. Melnitzer, who co-owns a wholesale bakery with her husband, has been involved with San Quentin since 2012 via the prison’s TRUST (Teaching Responsibility Utilizing Sociological Training) rehabilitative program. Dombroski is a former chef who used to work for Chef’s Warehouse, a food distributor and one of the program’s main sponsors.

Before they met in 2015, Melnitzer and Dombroski had been independently pushing for a culinary program at San Quentin. Because of their experience in the food industry, they saw a staffing gap that they thought former inmates could fill.

“As important as these groups [like TRUST and others] are … what are we giving them? They haven’t been professionally educated,” Melnitzer said. “And that’s when it struck me: Let’s do a cooking program. I’m in the industry. We need employment. People won’t judge them for their past or their tattoos.”

It took about two years of planning and clearing red tape to get the program up and running. The project kept having false starts until Melnitzer got hold of San Quentin spokesman, Lt. Sam Robinson, who connected them to Warden Ron Davis.

Quentin Cooks was born in 2016. There are two sessions a year, at a cost of $20,000, Dombroski said. Last year, one session was canceled.

Fresh Aprons, Clean Slates

Melnitzer, Dombroski and Thornton, the lead instructor of Quentin Cooks, say they do all they can to ensure the guys are walking into the class as equals. They keep the conversations forward-looking and avoid asking about the men’s crimes.

“We do ask that the men check their egos at the door,” Dombroski said. “Differences are really put aside to allow for people to … show up as they are.”

When the guys are nearing release, Melnitzer starts reaching out to her network in the area where they’re paroling to set up interviews and drum up interest in them.

One of this year’s Quentin Cooks, Daniel Martinez, paroled the weekend before the graduation dinner. At the inmates’ last class, he said he’d previously managed grocery stores and restaurants and he was looking forward to starting over back home in Sacramento. Thanks to Melnitzer and some old friends, Martinez said he has already gotten a lot of leads on jobs.

Martinez wasn’t permitted to return to San Quentin for the graduation dinner since he’d just been paroled, but he sent a letter to his classmates. Melnitzer introduced it, explaining how hard Martinez tried to get permission to come back for the dinner — making light of the irony of a former inmate clambering to get back into prison days after his release.

“Dear my fellow chefs … I can only imagine how well you guys are going to do on the dinner. Blow their socks off. I made lemon chicken, rice, asparagus and cucumbers topped with pistachio and pine nut dressing for my wife and parents. They loved it! One more thing, we’re all famous on the internet on YouTube right now. I’ve seen pictures and videos of us. We look great!” Martinez wrote.

In the kitchen, the guys kid around with each other and the instructors. Inmate Phillip Sims dabs Thornton’s sweaty brow when Thornton struggles to wrangle a pasta maker. Several inmates comment that the class feels more like the outside than many of their other rehabilitative programs.

“When they come in here and they put on that apron, it really is supposed to be a three-hour escape for them,” Thornton said.

Asking for a Second Chance

At the graduation dinner, Melnitzer has tucked an article recently written about the men into their diplomas. As they file through to accept them to rounds of applause, she tells Ron Simmons, a Quentin Cook who is paroling soon, that she has put the contact information for a new lead in with his certificate.

Though the program does provide positive socialization and an escape for the men, the goal is for them to find employment — and the surrounding stability that can provide — as soon after release as possible. San Quentin did not confirm whether they keep data on former inmates’ employment rates, but Melnitzer says she keeps track of the men’s progress post-release independently.

However, the Prison Policy Initiative last year analyzed national data from 2008 (the most recent numbers available), determining that the unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people was nearly five times higher than that of the general population.

Unemployment rates for former inmates were highest (nearly 32%) during the first two years after release, so providing a more immediate route to employment post-release is pivotal, the group said.

Melnitzer is frank about the struggles she has keeping track of the men after they get out, and she doesn’t blame them when they don’t always stay in touch.

“I want them to get in touch with me. I want to empower them, but I get it. Some men, they’re overwhelmed,” she said, noting one man would write her an email — and it would all be in the subject line. “They’re lost, and when you feel so overwhelmed on so many levels, reaching out even becomes another pressure.”

That doesn’t mean there aren’t success stories. Joel McCarter, a graduate of Quentin Cooks who was released in 2017, was at the graduation dinner with his employer, Tina Ferguson-Riffe, who runs Smoke Berkeley, a barbecue joint in the East Bay. McCarter has been working in the food and beverage industry since he was paroled.

“Coming out, it’s kind of hard having to ask people for a second chance, but with San Quentin Cooks, it’s already there for you, so all you gotta do is come out and just reach for it and take it,” he said. “It’s been a blessing in my life.”