In a migrant shelter inside a former courthouse in downtown San Diego, medical personnel from local health clinics navigated through rows of green cots, stopping to check the temperatures and blood pressure of migrant parents and their children. Down the hall, physicians from the county and UC San Diego conducted initial health screenings for new arrivals.

‘We Have No Choice’: San Diego Officials Coping With Influx of Migrants, Flu Outbreak

“Every single migrant that ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) releases to our shelter, we’re sure that they have medical screening,” Jewish Family Service CEO Michael Hopkins explained, walking briskly from one floor of the shelter to another, passing charts showing how long it takes to get to different states by bus and plane.

“Ultimately we’re trying to figure out if they are healthy to travel, because we want to make sure that anyone who — if you’re on an airplane, you want to make sure the person next to you doesn’t have a communicable disease,” he said.

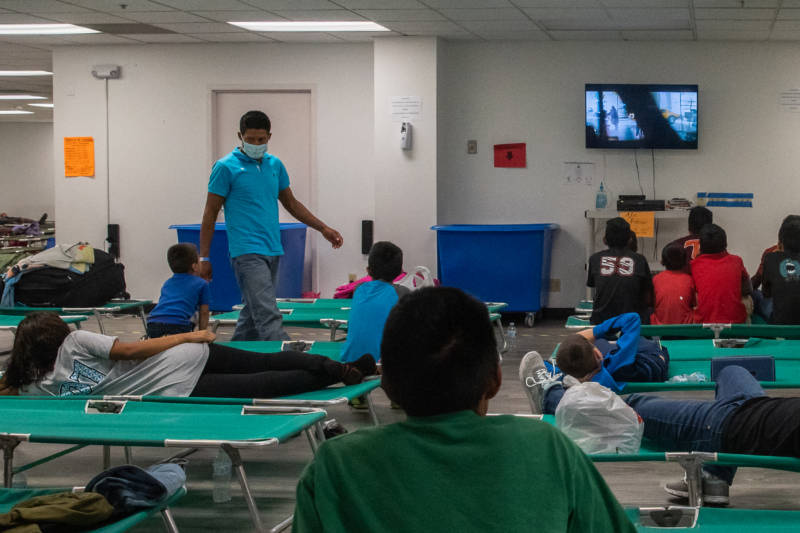

In one area, a group of children were clustered together on one cot to watch a movie. All of the adults were wearing electronic ankle monitors.

“I don’t think you’re gonna find a day that migrants are sleeping on the street because either the government or the nonprofit community has said we can’t handle them,” Hopkins said. “We’re pretty committed to figuring out a way to handle the migrants that are here.”

Impact of Early Support

In recent days, county health officials and a coalition of nonprofits and faith-based organizations known as the San Diego Rapid Response Network have been responding to a flu outbreak among migrants recently arrived on government-chartered flights from south Texas Border Patrol facilities.

Hopkins and others say San Diego is well-equipped to deal with the flu outbreak because the immigrant service organizations have been getting support for months from the state and local governments to respond to the needs of earlier waves of migrants.

“We’re really pretty confident that the state of California will be the significant funder of this project,” Hopkins said. “In addition, we’ve literally raised over a million dollars through private philanthropy to help fund the operation.”

The shelter — run by Jewish Family Service — sprang into action last week after immigration authorities announced they’d be flying migrants from Texas to San Diego. At the time, they didn’t know that dozens of the arriving migrants would be suffering from the flu.

Migrant families from Texas began showing up at the shelter on May 19, the day before a 16-year-old Guatemalan boy with influenza died in Border Patrol custody in Texas.

So far, 47 migrants have been diagnosed with flu-like symptoms, according to the San Diego County Health and Human Services Agency. Fifteen are quarantined in hotels — down from two dozen. One person has been sent to the emergency room.

One-Way Ticket to San Diego

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) began flying the migrants to San Diego on May 17 to relieve overwhelmed Border Patrol facilities in the Rio Grande Valley. CBP standards state that detainees should generally not be held in holding facilities for longer than 72 hours, although the time limit is often exceeded.

To date, San Diego has received eight flights carrying approximately 130 migrants each, according to a Border Patrol spokesman. A CBP spokesman said the agency expects up to three flights per week moving forward, with 120-135 migrants on each flight.

Once the migrants arrive, they are bused to Border Patrol stations for processing and then handed over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. After ICE releases the migrants, they end up here at the shelter, where volunteers give them hot meals, fresh clothes and help them contact and eventually travel to relatives or sponsors in the U.S. to await their day in immigration court.

Some of the migrants arriving at the shelter have reported not having adequate access to food and water in government-run facilities. Medical staff have treated some for dehydration, Hopkins said.

“Depending on where they were — whether it’s a detention facility or Border Patrol station, it could be that they haven’t had food in 24 hours or 48 hours,” Hopkins explained.

It is unclear whether CBP plans to transport more migrants to other states and cities. Hopkins said he has received calls from county workers in Florida who anticipate they could receive migrants from federal immigration authorities next.

“The folks I was speaking with are preparing for hurricane season, not migrant season,” Hopkins said. “Even though they have a lot of experience running emergency shelters for hurricanes, obviously this work with migrants is a wee bit different. They wanted to learn what we’ve learned along the way, so that if in fact migrants are sent to other parts of the country, they could be prepared.”

‘We Have No Choice’

The San Diego Rapid Response Network jumped into action last fall after the Trump administration ended a long-standing federal policy of helping migrants reach family in the U.S. upon release from ICE.

The shelter can house up to 200 people at a time and costs $450,000 a month to run. Jewish Family Service operates it with funding from the state as well as private donations. The county has made the former courthouse building available at virtually no cost. A new location is needed by the end of the year.

Since October, more than 14,000 migrants have received medical screenings from the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency, with help from UC San Diego.

Two local clinics that began volunteering medical care for the migrants are now being paid to provide health care with state funds that Gov. Gavin Newsom pledged earlier this year.

“I think it was late November when the county began to understand the numbers of individuals and the potential for health crisis if they weren’t involved,” Hopkins said.

County officials said if they had not had a system already in place, the flights and ensuing flu outbreak could have impacted San Diego’s hospitals.

“In reality, Border Patrol agents and so forth are not medical professionals,” said Dr. Nick Yphantides, San Diego County’s chief medical officer. “And if we didn’t have this in place, there would actually be a greater burden on our local emergency rooms.”

In April, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration for “releasing thousands of asylum-seekers onto the streets of San Diego without any resources.”

San Diego County Supervisor Nathan Fletcher said the Trump administration’s decision to stop helping migrants with travel arrangements forced San Diego to step in and respond.

“We have no choice. Their failure to do their job does not alleviate … the impact of their irresponsible behavior,” Fletcher said. “We have 15,000 people who have come through here, and so our choice is to create a centralized center, provide the services and resources, or have 15,000 people wandering the streets of San Diego, which has serious implications on public health, health care, public safety. And so we’re stepping up to do the very best we can in the federal government’s failure.”

Federal immigration authorities have for months reported that CBP facilities are overcrowded and unable to accommodate the high volume of parents and children showing up at the southern border.

“To mitigate the risk of holding family units past the time frame allotted to the government, ICE began curtailing all reviews of post-release plans from families apprehended along the southwest border starting on Tuesday, October 23,” ICE spokeswoman Lauren Mack told KQED.

“ICE continues to work with local and state officials and NGO partners in the area so they are prepared to provide assistance with transportation or other services,” Mack said.

Hopkins is not surprised that the San Diego shelter is where migrants from south Texas are ending up.

“I know that ICE and Border Patrol knows that we’ve got this down to a science,” Hopkins says. “And so if you were going to have planes drop off people anywhere in the country, it’s not a surprise that it’s here in San Diego because we’ve got this down.”