Rethinking Disaster Recovery After A California Town Is Leveled By Wildfire

When the Camp Fire raced into the Northern California town of Paradise on Nov. 8, destroying nearly 19,000 structures and claiming 85 lives, Chris Beaudis narrowly escaped. He drove out of the Sierra foothills in his Ford Bronco with only his pit bull. He lost everything and has no insurance.

“It’s been really stressful at times,” he says. “You think that it’s the end of the world, especially when everything you have is gone.”

All Beaudis has for now is a 300-square-foot FEMA camper trailer. It is wedged into a corner of the fairgrounds in Yuba City, in the valley about 50 miles south of what’s left of Paradise. His is one of about 7,200 Camp Fire survivor households relying on direct federal aid, according to FEMA.

“Thank God that I was finally able to get on the help list and receive help,” Beaudis says. “Since then it’s just been the biggest stress reliever of my life.”

With nowhere else to go, Beaudis is likely to stay in this trailer for another year before he can rebuild.

But that help list that Beaudis was able to get on is emblematic of a bigger problem in the way we respond to natural disasters: Disaster strikes, emergency help is deployed, checks are cut, communities are rebuilt — even in high-risk places. Many say that reactive response has to change.

Thus far, the federal government — through FEMA — has paid out more than $85 million in emergency aid for survivors. An additional $370 million in loans has been distributed by the Small Business Administration.

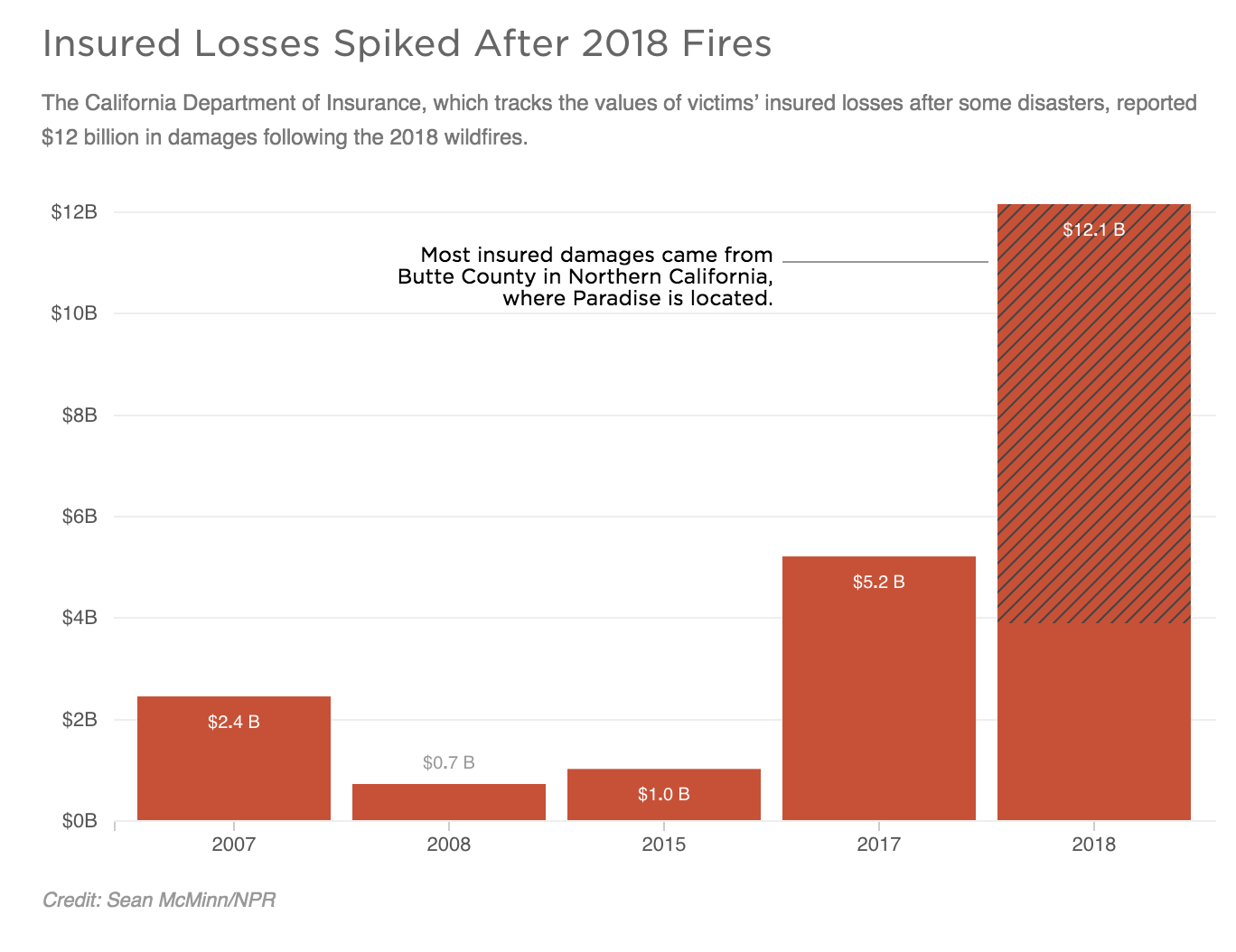

One estimate put the Camp Fire as the most expensive disaster in the world in 2018, racking up more than $16 billion in losses.

Reactionary mode

As disasters like wildfires, floods and hurricanes increase in size, severity and frequency, experts who study our response to them are warning that events like the Camp Fire should be a wake-up call. One of the early lessons from Paradise is that we need to radically overhaul how to prepare for and respond to disasters in the era of climate change, they say.

“We have been very reactionary,” says Josh Sawislak, a climate resiliency adviser in the Obama administration. “The problem is that we’ve kind of gotten away with it for a while.”

FEMA will typically respond to a disaster, arriving immediately on the ground, and then spend the next 18 months or so cleaning up, aiding communities and making the recovery process as easy as possible for disaster victims who want to rebuild.

In Paradise, that mission started with cleaning up the rubble from destroyed homes, strip malls, gas stations, and the torched frames of cars being scooped up and hauled away.

Debris removal alone is estimated to cost upwards of $1.7 billion, again mostly paid for by federal taxpayers.

“The quicker we remove the debris, the faster reconstruction can start,” says Bob Fenton, FEMA’s Region 9 administrator, overseeing the California wildfire recovery.

Clean up the debris and rebuild — this has been the mindset for disaster recovery in the U.S. for decades, according to experts like Sawislak, who has worked in disaster relief and now studies the industry. We wait until something happens and then come in and fix it. This model is outdated and broken, Sawislak says.

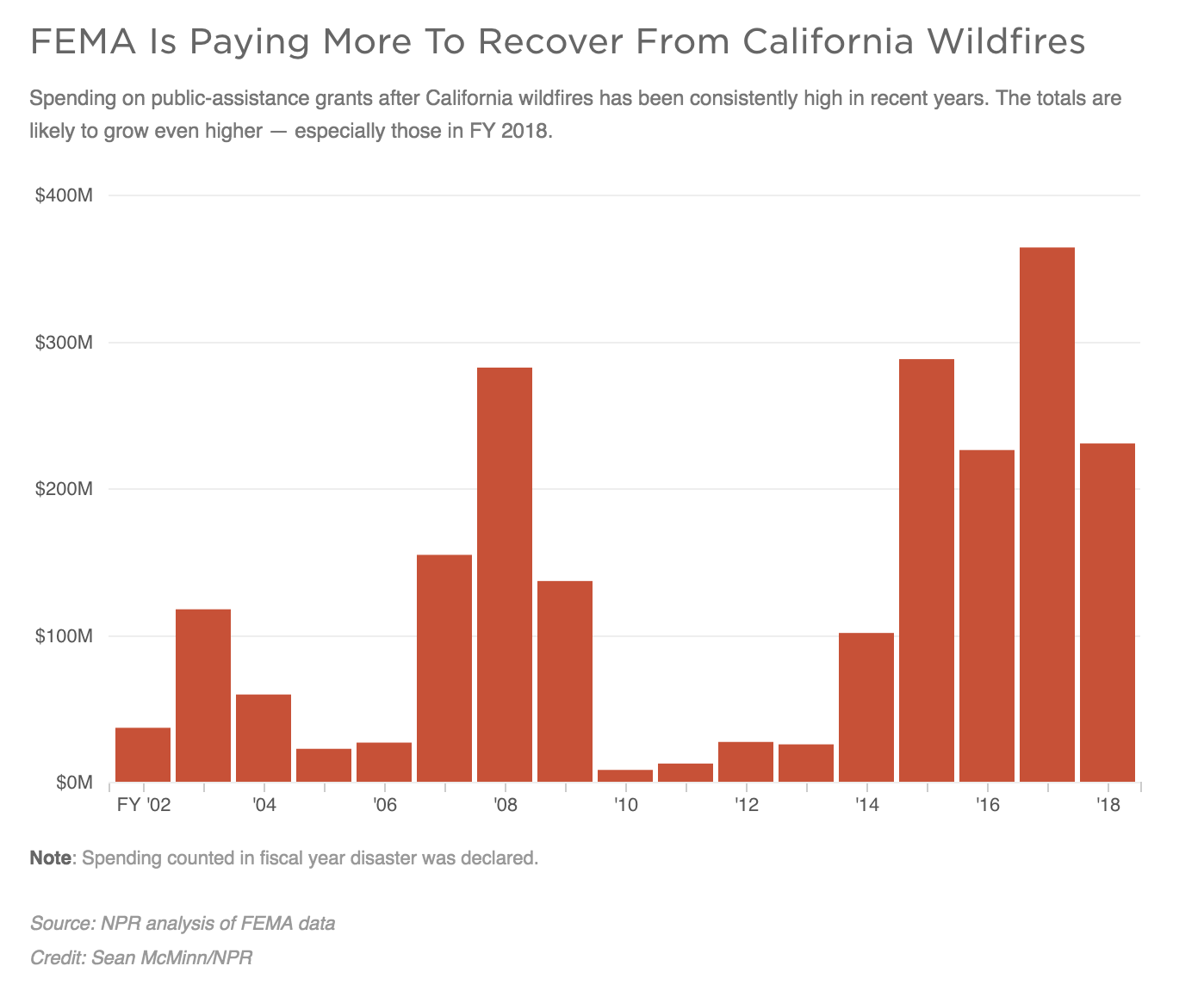

“We’re spending more and more money and it’s going to get even worse,” he says. “Climate change is going to force our hand to be smarter about how we do this.”

Sawislak says it is standard operating procedure to cut checks after a disaster declaration. Just last week the Senate passed a $19.1 billion dollar disaster relief package to aid farmers and communities as they recover from floods, hurricanes and wildfires. But every year the U.S. seems to be experiencing the biggest hurricane, the deadliest flood and the most catastrophic wildfires — like the Camp Fire — burning into whole cities that are built in and around overgrown, dry forests.

Behavioral scientist Kathleen Tierney says a lesson from Paradise is that staying the current course will bankrupt the federal Treasury.

“We may be able to slow down the losses, but we can’t stop them,” she says. “This is the legacy; this is the bill that has come due.”

Optimism bias

Tierney spent her career advising communities after disasters as the former director of the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware and the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado. She says it’s a basic human instinct to want to rebuild, to return to normal after a traumatic event, even if it’s going home to an area we know is risky.

“The tendency that a lot of people have is to say, ‘We’ve had our disaster. We’re not going to have another one; all we have to do is go back,’ ” she says.

Fenton, the FEMA administrator, has been thinking a lot about this, especially after Paradise. During the Obama administration, he led a committee to overhaul the way communities plan for catastrophes. He has been trying to move the needle toward persuading communities and states to do more before the inevitable disasters strike.

“We’ve done a lot of work over the years to help people respond or rebuild,” Fenton says. “But how do we get them to plan better, prepare better and mitigate against future disasters?”

It is not an easy task to turn this system around; there’s the ungainly federal budgeting process, political divisiveness and human nature, among other things.

Disaster recovery reforms

Still, last fall, amid a record wildfire season in California, Congress passed the Disaster Recovery Reform Act. It’s part of a sprawling set of disaster spending reforms that will, among other things, allow FEMA to send a portion of its disaster relief budget to states to use for pre-disaster mitigation.

Sawislak, who also served on the Hurricane Sandy recovery task force, says it’s a start toward avoiding massive rebuilding costs in the future.

“But I don’t think it goes far enough,” he says. “We should be spending billions on protecting our infrastructure and communities, not millions or even hundreds of millions.”

Indeed, it is a small portion — about 6% — netting an estimated $300 million a year for pre-disaster mitigation programs. And it is unlikely any of those funds will be allocated in time for this year’s fire season.

Nevertheless, federal officials like Fenton say the conversation is finally beginning in earnest around the West, where he says communities need to build — and rebuild — smarter.

“Communities need to be aware of those risks when doing community planning and not build in very high hazard areas,” he says.

Even after Paradise, local governments in the West are continuing to approve development in high-fire-risk places.

Paradise’s town council has pledged it will rebuild, while also insisting its new town will have a redesigned street grid and homes built with more fire-resistant materials.

“We all want to rebuild and our constituents all want to rebuild,” says Jody Jones, the mayor. “But we want to rebuild a more resilient, safe community.”

For now, federal money is continuing to keep the recovery here going. The cleanup and debris removal alone is a monumental task, a fraction of which had been completed even six months after the fire.

So there’s time to rethink what the new Paradise will be.

Living with fire

One morning at dawn, Paradise Recreation and Parks Director Dan Efseaff walks along a ridge on the eastern edge of town. To his right, a steep drop into the Little Feather River Canyon. To his left is a narrow road, full of houses, all leveled by the fire, built right up along the ridge.

Efseaff is floating an idea to buy out these properties and turn the land into open space. The land could be a park but also managed as a firebreak, a place where crews could safely park engines and take a stand.

“The amount of resources that we spend during a disaster — it’s a million dollars a day, or it’s $10 million a day,” Efseaff says. “Yet I wish I had a million dollars for this next year to do vegetation work in here.”

There is a provision — and money — in that new disaster reform bill for states to buy out private property in high-risk zones and turn it into green space. This has never been done before in high-fire-risk areas in the United States. But it could be the future.

“California needs to figure out, how do we live with fire, how do we adapt to fire,” Efseaff says. “What we do in Paradise has huge implications for not only the state but the country.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))