It has vexed San Francisco’s leaders for more than three decades.

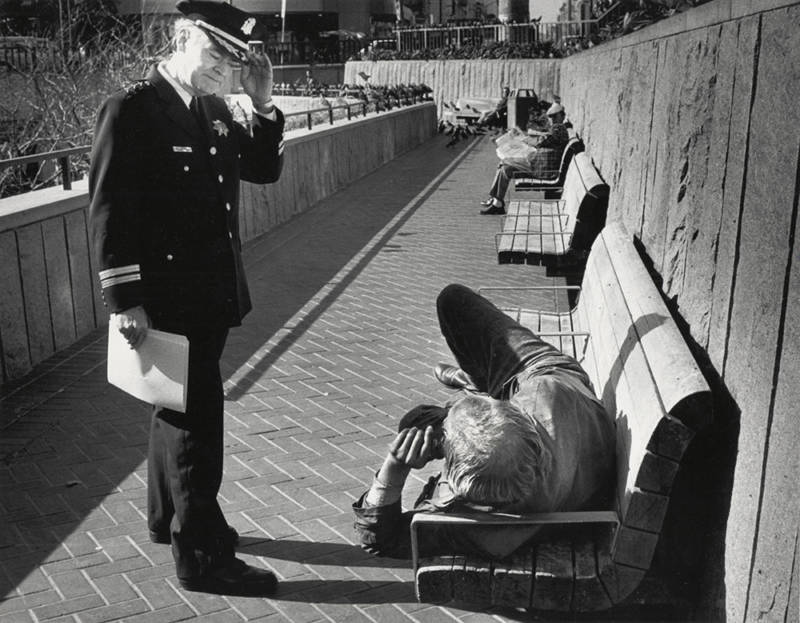

The last seven mayors — from Dianne Feinstein to London Breed — have all tried to tackle the city’s persistent homelessness, introducing scores of different plans and task forces, each of which has ultimately failed to markedly reduce the sheer number of people living on the streets. Consistently ranked among the most pressing concerns for San Francisco’s residents, homelessness has proved to be a political lightning rod in a city known for its progressive views, innovative spirit and enormous income gaps.

There have, of course, been some successes along the way, though progress has often been hard to notice. Over the last 15 years, the city estimates that it has housed more than 26,000 homeless people. But that’s come at tremendous cost: The city spent more than $300 million on homeless prevention services in 2018, and yet the day-to-day population didn’t dip. It actually grew, to more than 8,000, according to city’s latest point-in-time count (and that didn’t include the nearly 1,800 additional homeless people who were counted in jails, hospitals and rehabilitation facilities).

The following timeline describes the various ways each of the city’s last seven mayors has tried to tackle this intractable issue. View it interactively or in text format below.

Photos used with permission from the San Francisco Chronicle.

1975-1982: A Perfect Storm

San Francisco’s long-term homeless population remained relatively small through the 1970s. “We didn’t even call them homeless people,” recalls journalist Steve Talbot, a longtime city resident. In the early 1980s, though, homelessness became a full-blown crisis throughout the country.

The crisis was a decade in the making — the result of a combination of massive state and federal cuts to mental health services and public housing, a wave of Vietnam veterans in need of help, skyrocketing home prices and a spike in unemployment caused by the national recession. San Francisco was hit particularly hard, especially in the Tenderloin and other downtown neighborhoods.

1982-1988: Feinstein’s Muni Bus Shelters

Mayor Dianne Feinstein approached the homeless issue as a passing phenomenon. Rather than creating permanent housing and long-term services, her administration relied primarily on church-based emergency shelters, soup kitchens and city-funded overnight stays in cheap, private hotels.

The strategy proved costly and ultimately unsuccessful. Many of the shelters were poorly managed and underfunded, and fell quickly into disrepair. In one notorious instance, the city converted a set of old Muni buses into temporary shelters.

But after the city failed to provide adequate supervision, the facilities were vandalized and Feinstein ordered them evacuated and towed away. Contrary to the predictions of officials, the city’s homeless population continued to grow.

1988-1992: ‘Camp Agnos’

During his first year in office, Mayor Art Agnos, a social worker, unveiled his “beyond shelter” strategy, a sweeping initiative to provide services to the city’s homeless that he claimed would be a model for the nation. The plan called for building two centers — the first city-owned shelters — where homeless clients could be assessed and receive health and counseling services.

Agnos’s reputation, though, took a hit that summer when hundreds of homeless people set up camp in Civic Center Plaza. The press dubbed it “Camp Agnos.” For months, he allowed the camp and its residents to remain, but under mounting pressure, eventually ordered police to dismantle it. His string of shelters opened hastily in 1990 to accommodate victims of the October 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, but lacking adequate resources, they soon became overcrowded and understaffed.

The following year, Agnos was unseated by Frank Jordan, his former police chief, who pledged to dramatically change tack and deal with homelessness through a law-and-order approach.

1992-1996: Jordan’s ‘Matrix’

Soon after taking office, Mayor Frank Jordan instituted his Matrix program, an enforcement-based strategy using police to forcibly clear homeless people from the streets and steer them into health and housing services. During the first six months of the program, police issued 6,000 citations for quality-of-life misdemeanors.

Critics said the approach criminalized the poor and merely managed homelessness rather than doing anything to prevent it. But many residents and businesses, weary of deteriorating street conditions, supported the plan. In 1994, voters approved Jordan’s measures to ban loitering near ATMs and to replace part of city welfare checks with housing vouchers.

Without enough services in place to handle the uptick in numbers, though, little progress was made in preventing the homeless from returning to the streets. Similar to the fate of his predecessor, Jordan’s poorly performing homeless policies — used as ammunition by his challenger, Willie Brown — contributed to his failed re-election bid.

1996-2004: Brown’s Grand Vision

Mayor Willie Brown pledged to bring in outside government funding to expand social services and develop a regional plan with other Bay Area cities. But during the subsequent period of economic expansion and gentrification, fueled by the late 1990s dot-com boom, those plans fell short.

Brown did lead a successful increase in the city’s affordable housing stock, creating thousands of new units and beds by leasing and renovating cheap residential hotels and heavily subsidizing the rent. But he also took a number of controversial pro-development actions, such as increasing quality-of-life citations and closing the Mission Rock homeless shelter to build a parking lot adjacent to Oracle Park (then called SBC Park).

During his second term, Brown took little leadership on the issue, famously declaring homelessness a problem “that may not be solvable.” In 2002, the San Francisco’s homeless population spiked at more than 8,600, as the city became gripped by a housing shortage and skyrocketing costs amid the economic boom.

2004-2010: Newsom’s Supportive Housing

As a city supervisor, Gavin Newsom championed the controversial “Care Not Cash” measure, slashing cash payments to the homeless and redirecting funds toward housing. In his first year as mayor, he introduced an ambitious 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness by creating 3,000 housing units with supportive services and replacing emergency shelter beds with 24-hour clinics. Although the plan fell short of its goal, it did move thousands of homeless people off the streets over the next decade.

After the program’s first year, homelessness in the city dropped by nearly 30% from its 2002 high. But then the numbers froze — at over 6,000 people — through the remainder of his tenure. As mayor, Newsom also sponsored a measure approved by voters in 2010 that restricted sitting or lying on sidewalks. Homelessness, he later claimed, is the “manifestation of complete, abject failure as a society. We’ll never solve this at City Hall.”

2011-2017: Lee’s Department of Homelessness

Mayor Ed Lee, who was appointed after Newsom became lieutenant governor, initially devoted significantly less attention than his predecessor to homelessness. In an effort to woo major tech companies, Lee cleared areas in the Mid-Market district and nearby neighborhoods, and ordered large homeless camps dismantled. Criticized for avoiding the issue, Lee opened the city’s first navigation center in 2015, a 24-hour multiservice homeless shelter providing housing assistance and drug abuse rehabilitation.

A month into his second full term, Lee announced a new citywide homeless department, an effort to group all services under one roof and spend at least $1 billion over the following four years to help thousands of people find supportive housing. The department launched in July 2016. A year later, it reported a double-digit decrease in family and youth homelessness, but a slight rise in the number of single homeless adults.

Lee then launched a “coordinated entry” initiative to consolidate the dozens of city-funded homeless service groups under one system and have a shared database. Meanwhile, public complaints about encampments, human waste and needles increased sharply, from about 6,300 in 2011 to more than 44,000 in 2016, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

2018-Today: Breed’s ‘Housing First’ Push

Mayor London Breed entered office pledging to further the reach of programs established by her predecessor. Early on, she committed to adding at least 1,000 new shelter beds by 2020 and upheld Lee’s promise of building 5,000 units of housing annually, significantly expanding the city’s affordable housing stock and protecting existing affordable units.

Breed has also proposed expanding the number of navigation centers throughout the city — including a recent proposal to open a safe parking site for people living in their vehicles — and strongly supports safe injection sites for drug users.

Since October 2018, her administration has added nearly 300 shelter beds, with proposals for about 500 more, and helped move some 1,500 people off the streets since she took office, with drops in veteran and youth homelessness.

Nevertheless, a one-night homeless count in January identified nearly 9,800 homeless people in San Francisco (including those in jails, hospitals and rehabilitation facilities) — more than half of them unsheltered — a 30% increase since 2017.

Additionally, some of Breed’s efforts to build new shelters have hit major roadblocks. Most notably, her plan to build a 200-bed navigation center on the Embarcadero this summer is now tied up in litigation after a neighborhood group sued to halt construction.

And despite Breed’s ongoing efforts to expedite the construction of affordable housing, the city netted just over 2,500 new units in 2018, a 42% decrease since 2017, marking the lowest gain in five years. Breed is now pushing the biggest affordable housing bond in San Francisco’s history, which would yield $600 million and up to 2,800 units if approved by voters in November.

Breed also angered key homeless advocates when she opposed Proposition C, which she said lacked proper accountability provisions. The measure, which voters decisively approved in November 2018, creates a new tax on large corporations, and is expected to bring in as much as $300 million annually for homeless services.