California fire officials have learned through hard experience to temper their optimism.

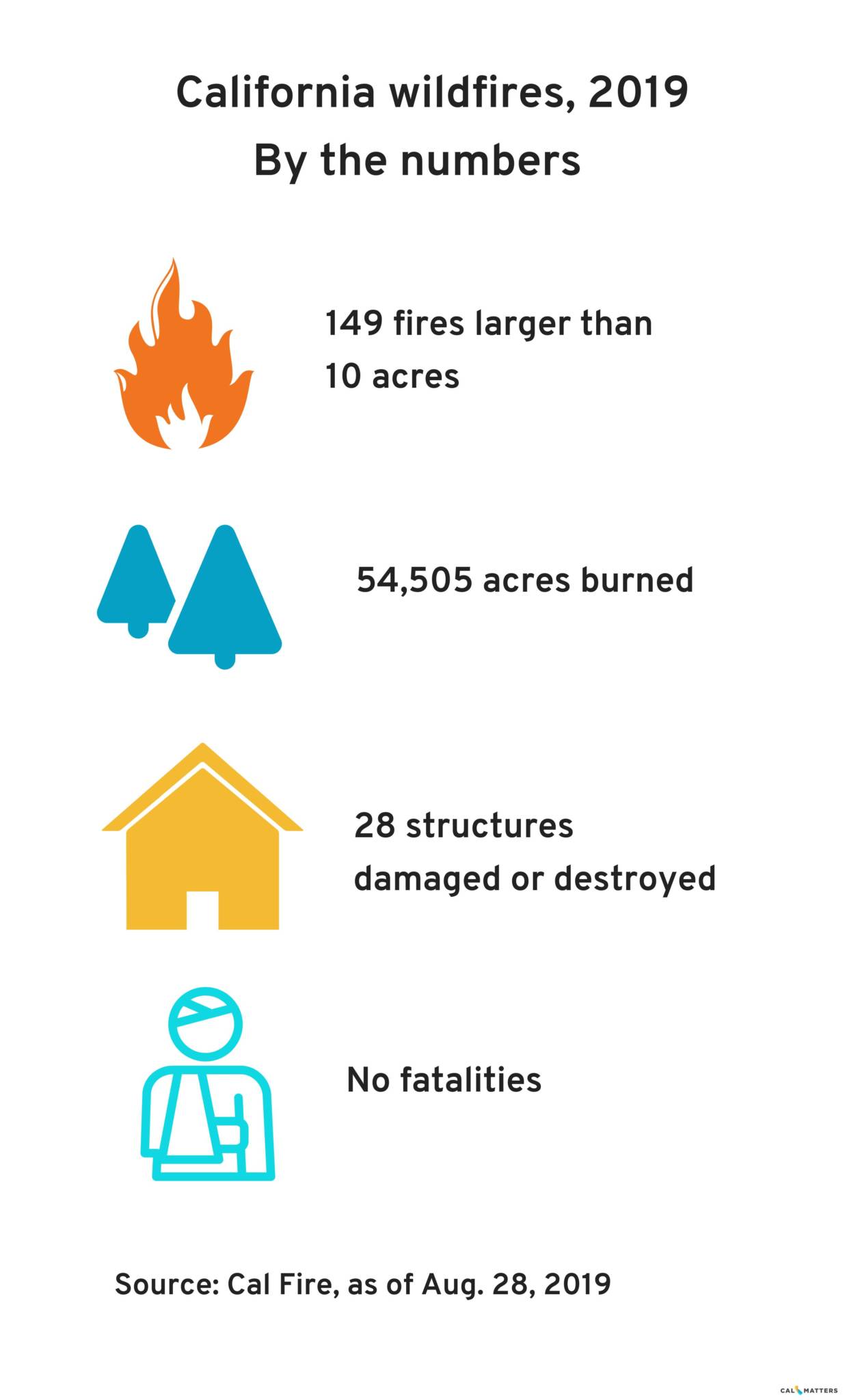

Having just endured more than a decade of rampaging fires — 14 of the 20 most destructive fires in state history have occurred since 2007 — fire bosses say this year the glass is half-full.

“We’ve got a few things going for us at the moment,” said Scott McLean, a spokesman for Cal Fire, the state firefighting agency. “We still have a snowpack. Our upper elevations haven’t dried out. Because of that, we are able to continue our fuel-reduction projects.”

Yes, this year featured a wet winter — usually good news for fire officials. But so did 2017, one of the state’s wettest winters in half a century and one of the most devastating years for wildfire.

Clearing and cutting has helped eliminate some of the brush and trees that fuel the flames. But California’s forests are still clogged with 147 million dead trees, and counting. And the late-winter rains encouraged the growth of grasses and other highly combustible plants.

Cal Fire battled 164 fires across the state in the third week of August, many of them small. History shows that September and October, with their hot, fierce winds, are the worst months for fire. And “this week we have dry lightning predicted,” McLean said. That could spark fires in the state’s northern forests.

On the other hand, state officials have been showering Cal Fire with financial aid. The agency’s ranks are bolstered by an additional 400 seasonal firefighters and 13 new engines and crews to operate them. And the state is taking delivery of a new Sikorsky S-70i Firehawk helicopter next month, the first of 12 replacement firefighting helicopters.

“We’ve got everything out of maintenance; everything’s ready,” McLean said.

But don’t look for California’s biggest air tool to come to a rescue anytime soon. The converted 747 jet, which can carry 24,0000 gallons of water or retardant, is currently flying over the Amazon, fighting fires in Brazil.

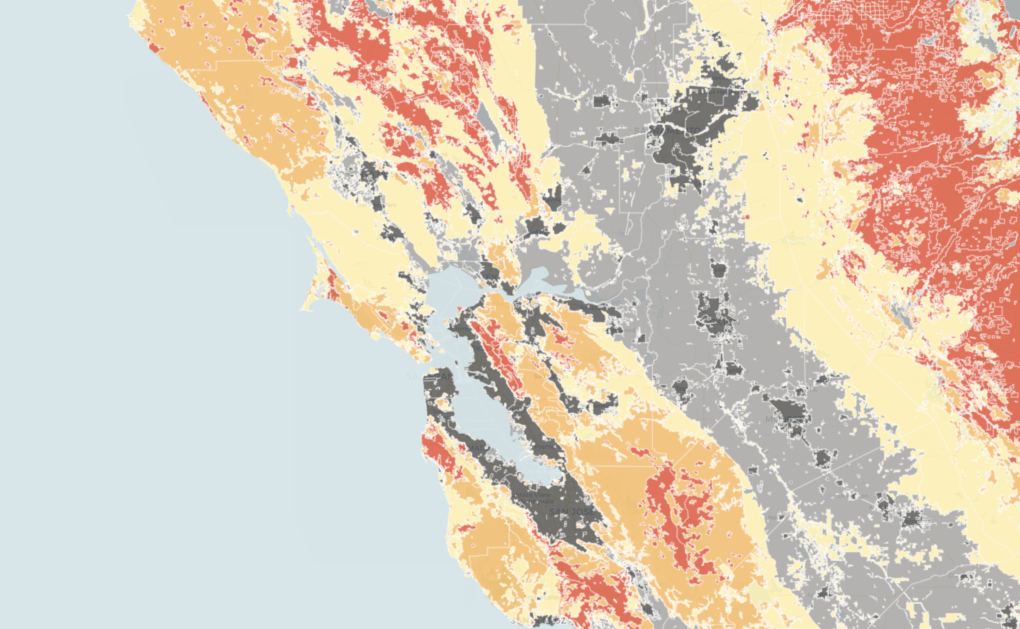

Mapping the Fire Threat

Cal Fire is in the process of updating its map of wildfire-hazard zones, identifying areas of fire danger and assigning degrees of risk to those places. The California Public Utilities Commission is revising its fire map as well. So are the state’s power providers and insurance companies.

They’re all trying to better predict where and how wildfires may strike, as officials across the state seek to gain some advantage over fire’s growing menace.

In the case of Cal Fire, the mapmaking — painstaking and devilishly complex, combining detailed data about weather, topography, vegetation and the placement of roads and homes — was last undertaken about 12 years ago. Officials say that doesn’t mean the 2007 version is out of date.