The USOC — which changed its name this year to the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee — ultimately moved to expel the two sprinters from the games, sending them back to San Jose the next day. The committee released a statement expressing its “profound regrets to the International Olympic Committee, to the Mexican Organizing Committee and to the people of Mexico for the discourtesy displayed by two members of its team.”

Under the leadership of Avery Brundage, a controversial figure who had previously been accused of racism and anti-Semitism, the IOC called the protest of black suffering in America “outrageous.”

“The action … was an insult to the Mexican hosts and a disgrace to the United States,” Brundage wrote in a letter months later.

At home, Smith and Carlos received death threats, and the FBI labeled them “rabble rousers” and started monitoring them.

The superstars from “Speed City,” as San Jose State was called at the time, were banned from international track and field competitions. This came at a time when Smith, who had already broken multiple speed records, was widely considered one of the fastest men in the world.

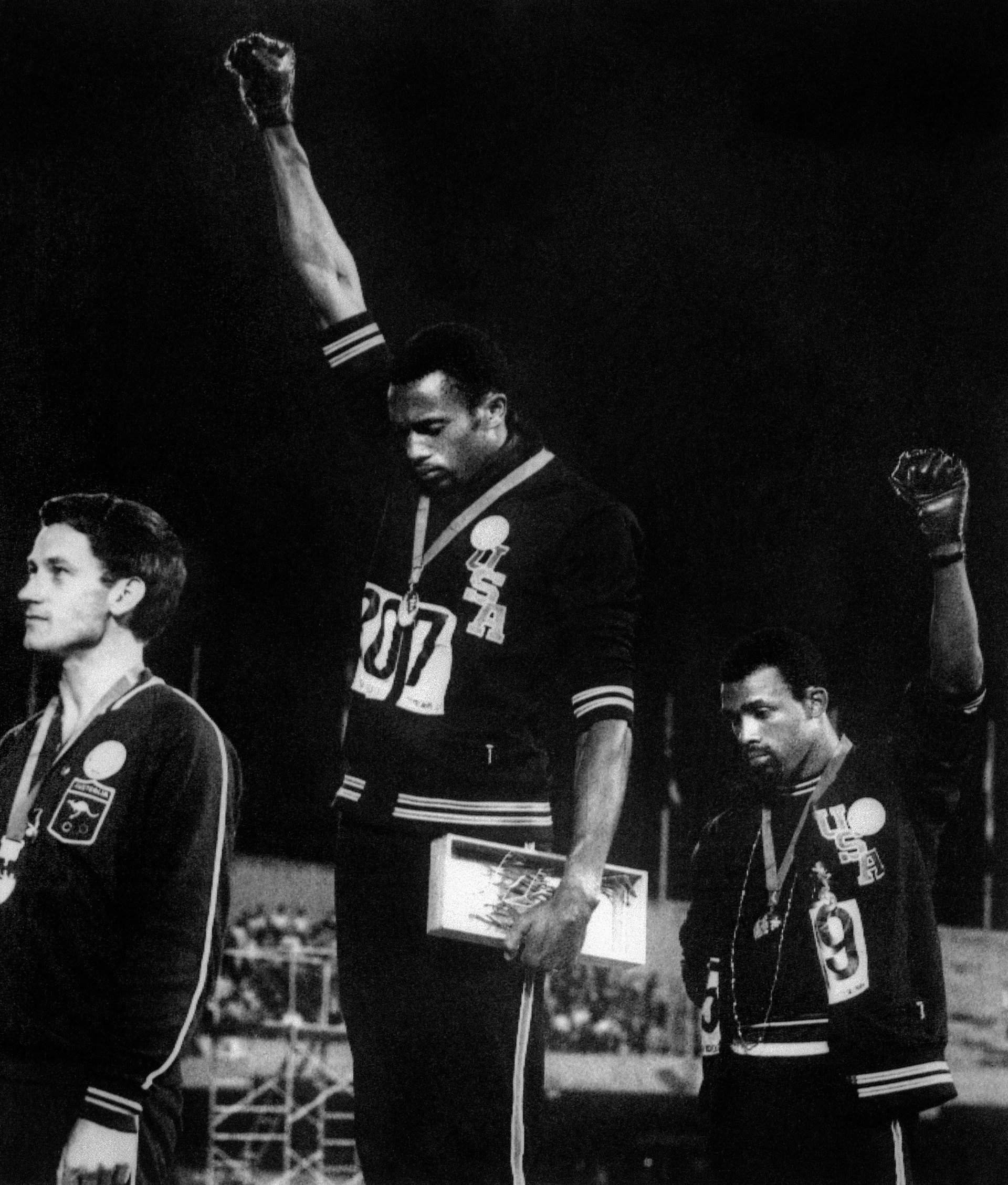

Over the years, attitudes toward the men began to change. In 1984, Smith and Carlos became emissaries for the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles and were subsequently inducted into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. And in 2005, the Associated Students of San Jose State University unveiled, in the center of the campus, a 23-foot-tall sculpture of the two athletes with their fists raised.

“We had to do something that would be prestigious, respectable, pungent, shocking,” Carlos told attendees during a 2018 commemoration event at SJSU. “We didn’t give the finger. We didn’t wrap the flag around our head or tie it up like a diaper. We didn’t stand there with disrespect. We stood there to say, ‘Hey man, I’m America. I’m your son and I’m wounded. I’m not wounded for me, because I’m one of your heroes. I’m in the Olympics. But I’m wounded for the race.’ … That’s why we went to Mexico City.”