A San Francisco teenager claimed in late 2015 that counselors at a now shuttered Pennsylvania reform school assaulted kids at the facility, allegations that were substantiated by California regulators and that contradict statements made by San Francisco’s top juvenile justice official.

Despite Denials, SF Officials Knew of Abuse at Reform School Where City Sent Juveniles

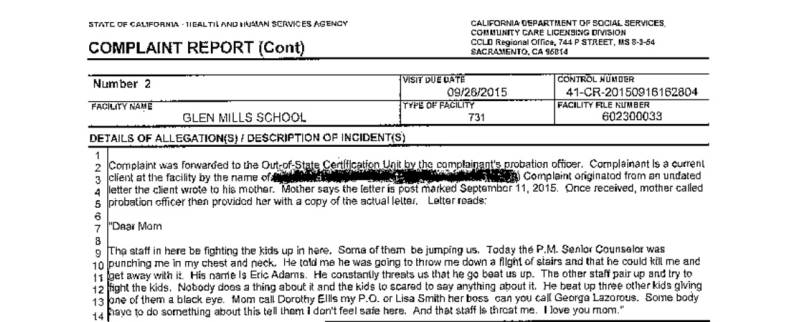

“The staff in here be fighting the kids up in here. Some of them be jumping us,” the unidentified juvenile wrote in the letter postmarked Sept. 11, 2015, to his mother about his experience at the Glen Mills Schools in suburban Philadelphia. The letter is transcribed in California investigative reports obtained by KQED.

“Today the P.M. Senior Counselor was punching me in my chest and neck. He told me he was going to throw me down a flight of stairs and that he could kill me and get away with it,” the teen wrote. “He constantly threats us that he go beat us up.”

In February, a Philadelphia Inquirer investigation revealed allegations of extreme physical abuse by some staff at Glen Mills, which was considered the nation’s oldest “reform school” for male youth.

The newspaper’s reporting, which also pointed to efforts by the schools’ officials to cover up the allegations, led Pennsylvania regulators to close the school’s campus, revoke its licenses and pull out juveniles housed there. Glen Mills is appealing the closure.

For years California counties sent scores of teenage boys in trouble with the law to Glen Mills, one of a number of facilities outside California used for juvenile placement.

Allen Nance, San Francisco’s top juvenile probation official, told KQED in April that he had never heard of problems from any of the some 30 boys the city had sent to Glen Mills over the last decade.

Nance, who recently lost a political battle to stop the closure — in late 2021 — of the juvenile hall he runs, said then that his department was “very fond” of the school.

“In fact, among our juvenile justice practitioners, Glen Mills was one of the more popular placement sites for some our most difficult-to-place youth,” Nance said then. “We were fortunate to not have had any bad experiences with Glen Mills.”

That contradicts documents obtained from the California Department of Social Services through a California Public Records Act request that show San Francisco officials were aware of the boy’s claim of widespread abuse at Glen Mills and kept in the loop on the department’s investigation into them.

In response to questions last week about the state investigation omitted from his previous answers, Nance said he has requested that his staff research the matter and he would respond when he had more information. He failed to provide an explanation in time for a Monday deadline.

The allegations came to the attention of state regulators after the boy’s mother called Dorothy Ellis, a deputy probation officer in San Francisco’s Juvenile Probation Department, the records show. Ellis then referred the information to the state Department of Social Services.

“Hello Carol and Ron I am sending this email to report an allegation of abuse at Glen Mills,” Ellis wrote in a Sept. 16, 2015, email.

The boy’s letter prompted an investigations by California social services officials, who are required to certify out-of-state facilities where juveniles are placed and investigate allegations of abuse at those places.

The teen’s letter recounts abuse toward him and others at the reform school.

“The other staff pair up and try to fight the kids. Nobody does a thing about it and the kids to scared to say anything about it. He beat up three other kids giving one of them a black eye,” the San Francisco boy wrote to his mother.

The boy asked her to call his probation officer or the officer’s supervisor.

“Some body have to do something about this tell them I don’t feel safe here. And that staff is threat me. I love you mom,” he wrote.

A California Department of Social Services analyst investigated the accusations, which included interviewing the boy and other kids at Glen Mills.

California officials sent their findings to the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services on Oct. 12, 2015, naming the staff member accused of abuse, and substantiating the teen’s claims.

“It is our stance that staff Eric Adams is indeed conducting acts of physical pain including punching resulting in client injury and fear,” the analyst, Ronald Leslie, wrote. “As a result, we do not feel California youth are safe in his presence.”

Glen Mills placed Adams on administrative leave the next day. A week later he was fired, representing the only case in which an investigation from California regulators led to the termination of an employee at the Pennsylvania reform school, according to Adam Weintraub, a spokesman for the state Department of Social Services.

Jeff Jubelirer, a spokesman for Glen Mills, would not provide more details about the case other than to confirm that Adams was fired in a move prompted by California’s review.

“Mr. Adams was terminated surrounding allegations of abuse that were substantiated by the state of California,” Jubelirer said in an email.

According to his LinkedIn page, Adams worked at Glen Mills for close to three years.

Adams declined to comment.

San Francisco stopped sending juveniles to Glen Mills in 2016, San Francisco juvenile probation chief Nance said last spring. He said then that the decision to halt the relationship with the reform school had nothing to do with concerns about abuse there.

In the weeks after the Inquirer published its investigation into Glen Mills, Pennsylvania regulators closed the campus and revoked its licenses, a move that Glen Mills has appealed.

You can find more on the Inquirer’s investigation into Glen Mills and its aftermath by visiting the author page of the reporter who broke the story, Lisa Gartner.