These days, thoughts of the silent screen era in the San Francisco Bay Area typically call up footage of Market Street shot by the Miles Brothers just days before the 1906 earthquake laid the city to waste.

San Francisco was a choice location for movie shoots at the turn of the 20th century, but fog and chill led at least one filmmaker from parts East to settle a wee bit farther south, in Niles, California.

I know this because José Muñoz, who grew up in Fremont, asked Bay Curious to look into the history for him.

“I’ve always been fascinated by movies, always watched movies,” Muñoz said, and his parents told him something he’s wondered about for years: Movies were once made in Fremont.

“I wanted to reach out to you guys to get more insight on the matter, to see if we could say that Fremont was the first Hollywood,” he added.

Back in the day, before Niles became a Fremont neighborhood, it used to be its own town, with sunny, warm weather more akin to that in Southern California — and easy access by train to San Francisco and Chicago.

That all had tremendous appeal for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Co., run in part by “Broncho Billy” Anderson (born Maxwell Henry Aronson), the first Western movie star cowboy.

“Anderson had been traveling around the United States for three years, looking for the perfect weather and filming location for the Westerns that he was making,” explained David Kiehn, historian for the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, one of the most delightful offbeat museums you can visit in the region.

Anderson settled on Niles in 1912, and over the next four years Essanay made more than 350 films there. “It was the most successful silent film company in the Bay Area,” said Kiehn.

Fast and Furious

Film companies of the time churned out movies at the rate of several a week. They tended to be thin on plot and big on action; chase scenes and slapstick comedy. The companies hired a lot of actors from the world of vaudeville theater, actors with the physical stamina and comedic chops for this kind of work.

Broncho Billy spotted a rising talent at a rival film company in Hollywood: a young English comedian by the name of Charlie Chaplin.

“Chaplin had been working at the Keystone Film Co. for $150 a week, and his contract was almost up. And Broncho Billy’s righthand man, Jess Robbins, signed him at Essanay for $1,250 a week — and a $10,000 signing bonus,” said Kiehn.

It was an expensive bet that paid off for Essanay. Chaplin didn’t particularly like Niles, which was, after all, a bit of a backwater compared to Los Angeles, but he made five films in Niles that cemented his standing as a movie star.

One of those was “The Tramp.” You can still visit the places where scenes were shot. For instance, consider the final, iconic scene of this movie, when our brokenhearted tramp waddles away from the camera in Niles Canyon. The area still looks a lot like it did back then, with big trees waving over a winding country road, albeit paved now.

Essanay allowed Chaplin to transition from being an ensemble performer, with a popular bit in someone else’s film, to a filmmaker himself, exercising creative control.

“Niles is pivotal,” said film history expert Marc Wanamaker. Chaplin, he said, fought for and achieved great autonomy with Essanay. “He could do whatever he wanted. This was the beginning of Chaplin as we know him.”

Chaplin itched to return to Hollywood, though, which by then was well on its way to becoming the center of the moviemaking universe. There, Chaplin made a few more movies for the company before striking out on his own as a producer.

The Niles studio kept on keeping on, until talkies became popular in the 1920s, and the film studio’s proximity to train tracks became an insurmountable problem.

A Temple to Silent Film

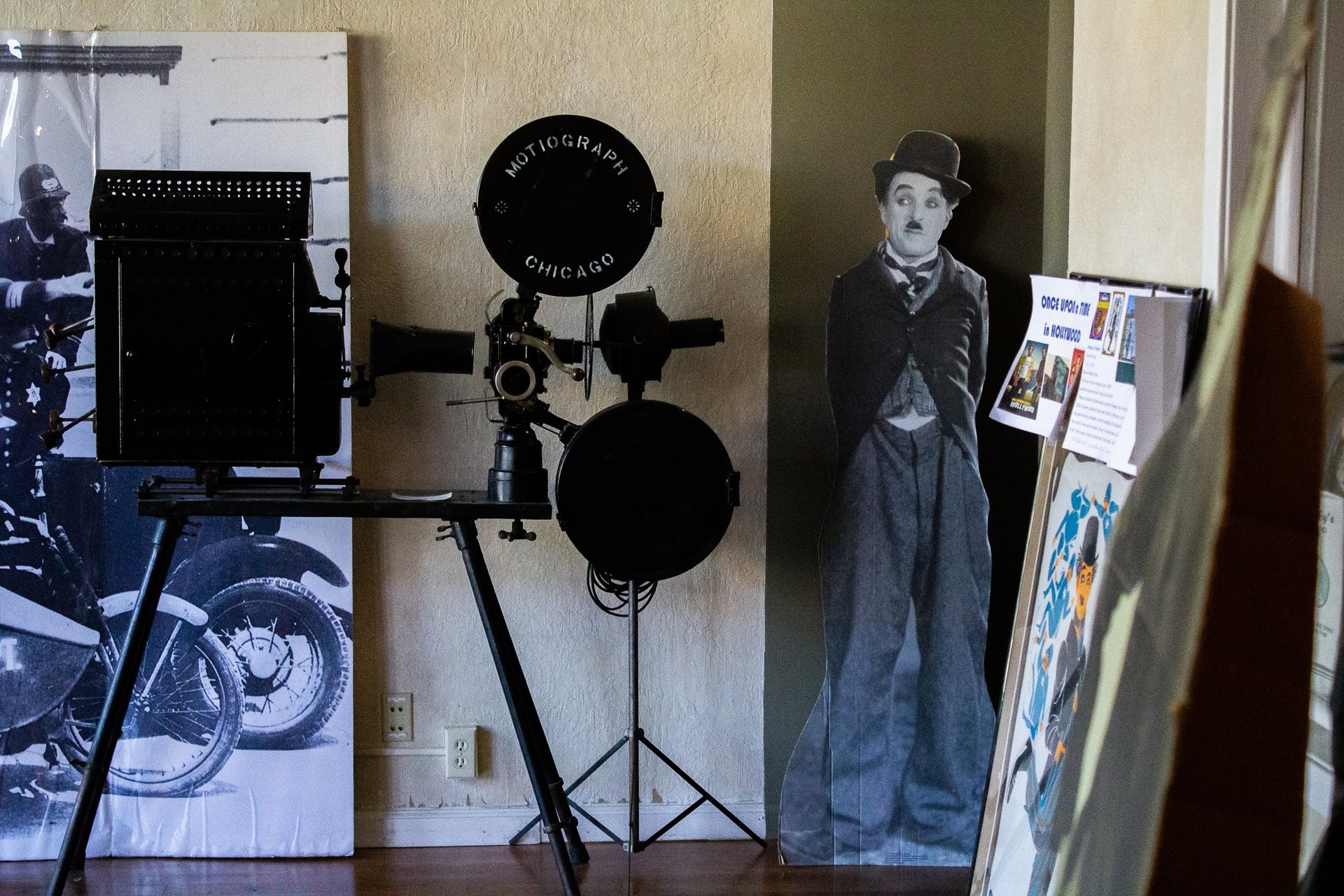

Fast forward to today, and the studio’s theater has become home to the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, itself home to an impressive and ever-growing archive of silent movies.

“Over 400 different silent feature films and over 600 silent short films. We’ve got a collection of 10,000 film prints that we show every Saturday night since Jan. 22, 2005, almost 15 years now,” Kiehn boasted, as he toured me around an impressive repository for beautifully restored and framed movie posters of the period, and the machinery of filmmaking, like early cameras and projectors.

Kiehn also repairs and researches the background of footage that people send here because they know Niles is a good home for silent film.

“It’s amazing what’s out there and what still is turning up. A family, not too long ago, brought us five nitrate films that were under a house in Stockton, rare films that I’ve never seen before,” he said.

Among the cache was one film, shot by the Miles Brothers in 1912 at Tanforan Park, of an aviation meet. Also, there was footage from the San Francisco earthquake aftermath in 1906. “Some pretty amazing stuff,” marveled Kiehn.

The silent film era lasted almost 40 years, from the 1890s through the 1920s.

“It’s amazing how many films that were made in that time period. Thousands and thousands of films. Only a fraction survive, but because there were so many made, there are still a lot of them around,” said Kiehn.

Sure, you could just watch some of these films on YouTube. But the musical choices are typically awful, and there’s something to be said for the visceral experience of watching a movie in a theater, with a live piano player, on a Saturday night.

Kiehn curates the schedule, which typically involves a feature and two shorts on any given night. Chaplin gets a lot of love, but so do some of the talents lesser known today but big in their time.

Consider Mabel Normand, with bouncy curls and expressive eyebrows. She was the first actress to be tied to the railroad tracks. She was at Keystone when Charlie Chaplin arrived, and taught him a few things before he moved on to Essanay.

She also directed some of the movies he was in, and served as his first leading lady for a stretch. Eventually, she even ran her own production company, just like Chaplin. Thanks to historians like Kiehn, we’re rediscovering treasures hidden in plain sight for close to a century now.

What does José Muñoz, who asked the question that prompted this story, have to say about what we found?

“It’s not only just a piece of history for Fremont or the Bay Area, but also all of California, ’cause people think moviemaking was born and still lives in SoCal, but this is as much as of a NorCal story as it is anything else.”