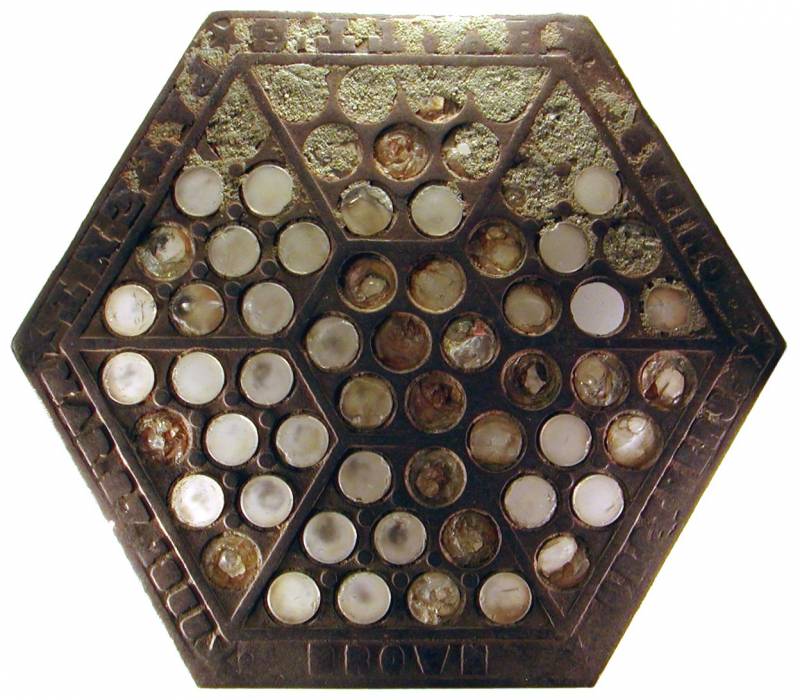

All over the city you can see glass squares and circles in big grid patterns covering a few feet of sidewalk. Sometimes the glass is clear, but often it’s a purple hue.

What are they?

They’re vault lights, which are essentially skylights for below ground. The little glass pieces are projecting sunlight down into subterranean spaces.

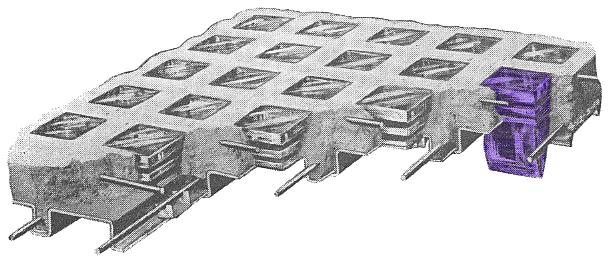

While the top of the glass is flat, so it doesn’t trip anyone, underneath the glass can take a variety of shapes. Some are shaped into prism forms that diffuse and bend the light so it reaches the inner areas of underground spaces.

Across the country, vault lights are used to illuminate a variety of iconic and interesting projects.

Vault lights were used to light some of New York City’s first subway stations and were placed in the ground of the opulent passenger concourse in the city’s original Pennsylvania Station. In that now destroyed icon, natural light would pour through the buildings arched glass canopy and would then spill down into the lower levels of the station through hundreds of vault lights in the ground.

In 1862, parts of Sacramento were raised as much as 14 feet to protect against flooding. (That year, California’s newly elected governor, Leland Stanford, was brought to his inauguration in a rowboat.) In some places, instead of lifting the building, they simply built over the first floor. Which means below the sidewalk it’s now possible to walk between abandoned storefronts, bathed in the purple glow of vault lights. Similar projects have taken place in cities across the country.

In San Francisco, vault lights are mostly used to illuminate sub-sidewalk basements — ie. basements that extend under the sidewalk. Often, these are used as extra storage or work space.

Why is the glass colored?

Glass is made of silica, which can be found in sand. Often, though, sand will have other elements in it too. In order to clarify and stabilize the glass from these other elements, chemists could use manganese dioxide. When vault lights were first installed, much of the glass was clear. But when the manganese is exposed to UV rays for long periods of time, it photo-oxidizes and turns purple or pinkish. Hence, the reason so much of the glass is now purple.

This process can take decades. So when you see colored glass, it’s either really old or someone dyed it to mimic the old glass.

Where were vault lights first used?

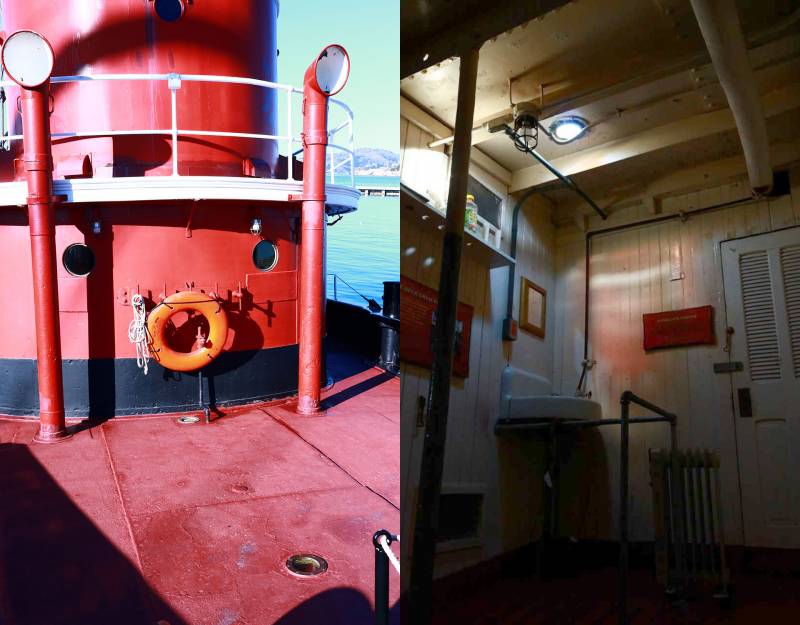

This kind of technology was used on ships as deck lights.

“It’s long been the traditional way of lighting the interior of ships. While kerosene lamps were sometimes used, the smoke could make interior spaces uncomfortable. And candles could become a fire hazard on wooden ships,” says Diane Cooper, a museum technician at the San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park.

The prisms inlaid into the deck were intended to direct light both down and up. The daylight comes down to light potential sleeping areas where sailors might forget about a candle. And if a fire breaks out below, the prisms would glow with warning for the sailors above.

“If you had coal in your hold, you’d need to be able to see that there’s light down there,” says Cooper.