When Nicole was growing up, her grandmother always told her: Don’t live anywhere built on artificial fill. Her uncle also had strong memories of watching the Marina District burn after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, when parts of the ground liquefied, causing buildings to collapse and gas lines to break.

Nicole wants to follow her grandmother’s advice, but she needs to know a few things: “What neighborhoods and cities in the Bay Area are built on filled land? And what are those cities and neighborhoods doing to mitigate the risk of liquefaction?”

What is fill?

Often, when we colloquially refer to fill around the Bay Area, we’re actually referring to two different things:

- Artificial fill

- Former or “reclaimed” marshlands and wetlands.

Artificial fill is land that was created by piling up soil, mud, rocks, rubble and dirt. In many cases, mud was pumped up from the bottom of the San Francisco Bay to fill in piles of rocks, then allowed to dry.

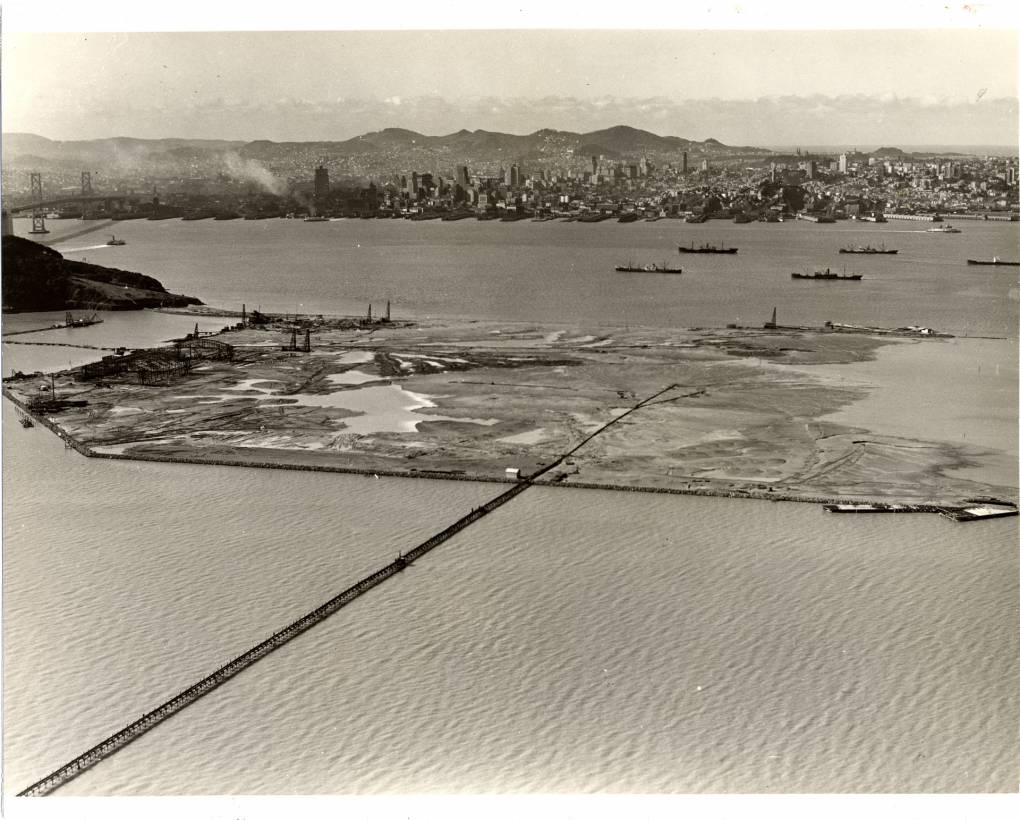

In most cases, this fill was put on top of low-lying areas or shallow wetlands and marshlands. For example, Treasure Island was made by piling rocks and mud on the shoals north of Yerba Buena Island. The land that is now the Marina neighborhood in San Francisco was originally filled in for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition — in some cases using debris and rubble from the 1906 earthquake.

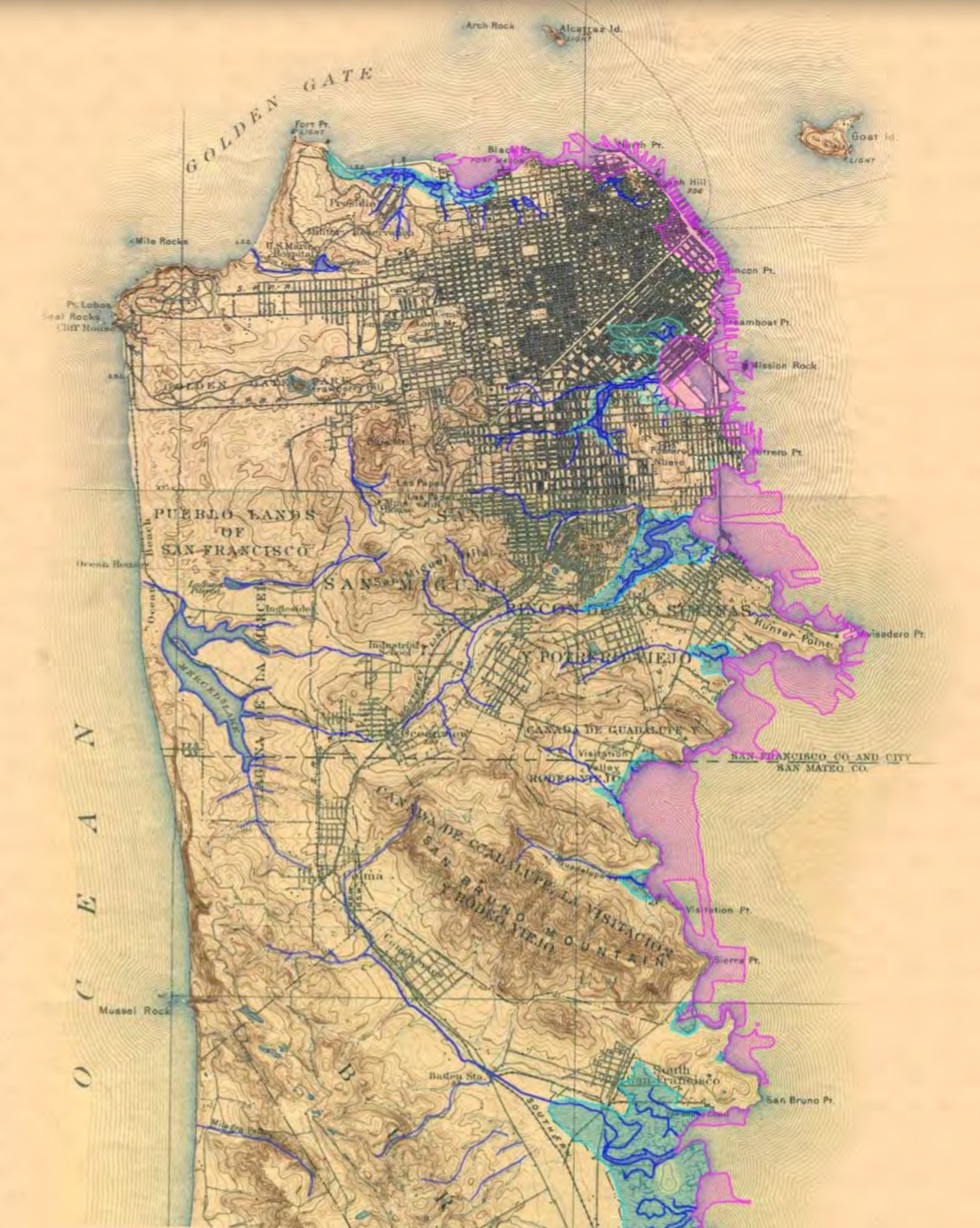

Reclaimed marshlands and wetlands are not technically fill. However, building levees and draining marshes did change the coastline of the bay, allowing for more development.

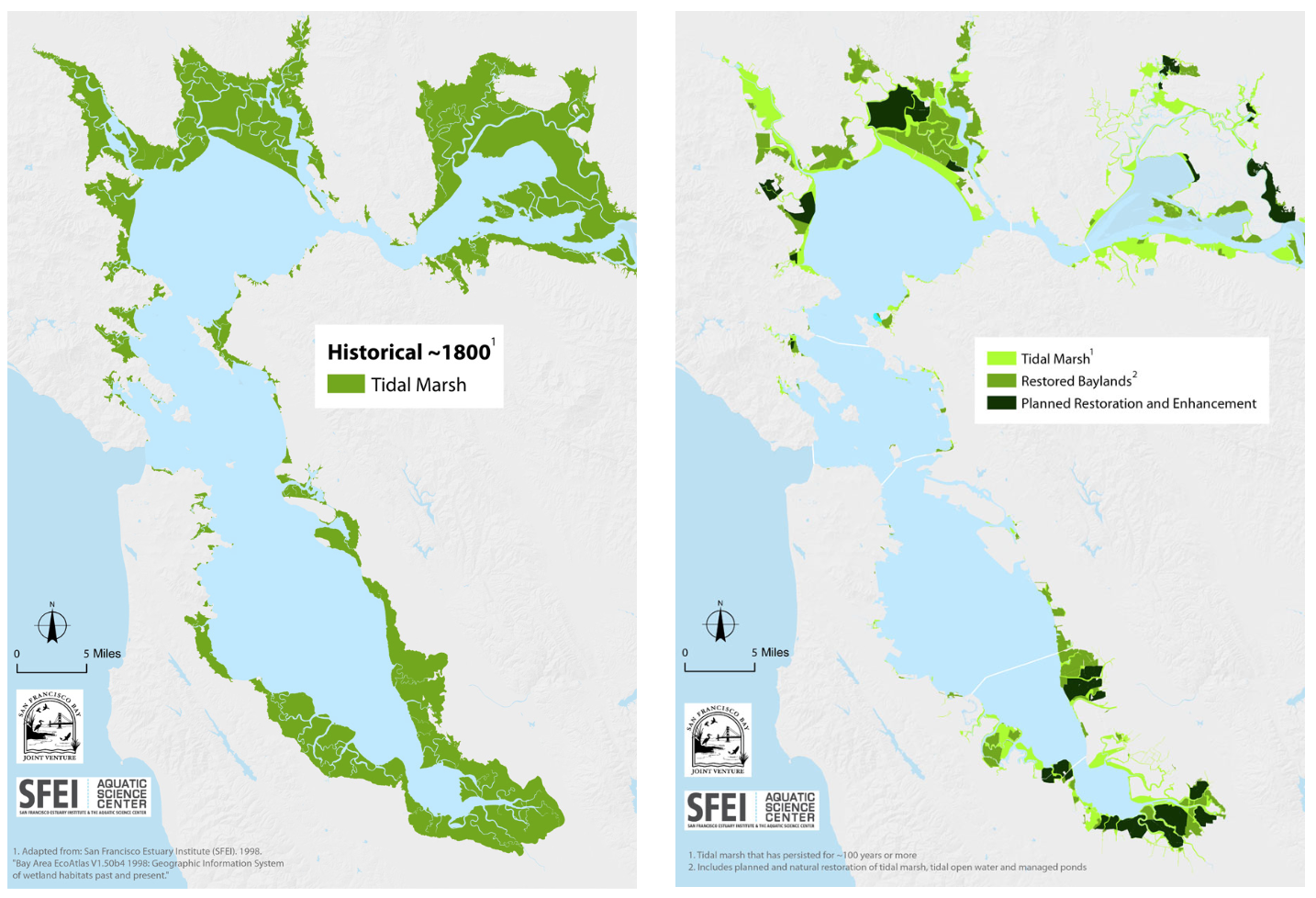

Hundreds of years ago, the coastline of the Bay Area looked very different. In many places, the edges of the bay were marshland or wetlands. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, lots of that got drained. People built levees and “reclaimed” the land for what they considered useful purposes, like agriculture. These days, some of those levees have been torn down and land is being returned to tidal marshes.

Why did we use fill in the Bay Area?

Because fill in the bay let us build, live and farm on land that was previously uninhabitable.

In the mid-1800s, the U.S. Congress passed the U.S. Swamp Land Acts. These were originally designed to help Louisiana drain its swamp lands and build levees — but were quickly put to use in other states. The laws allowed people to claim wetlands or marshlands as their own property if they drained it and used it for an agricultural purpose. This led to a spree of building levees and draining wetlands.

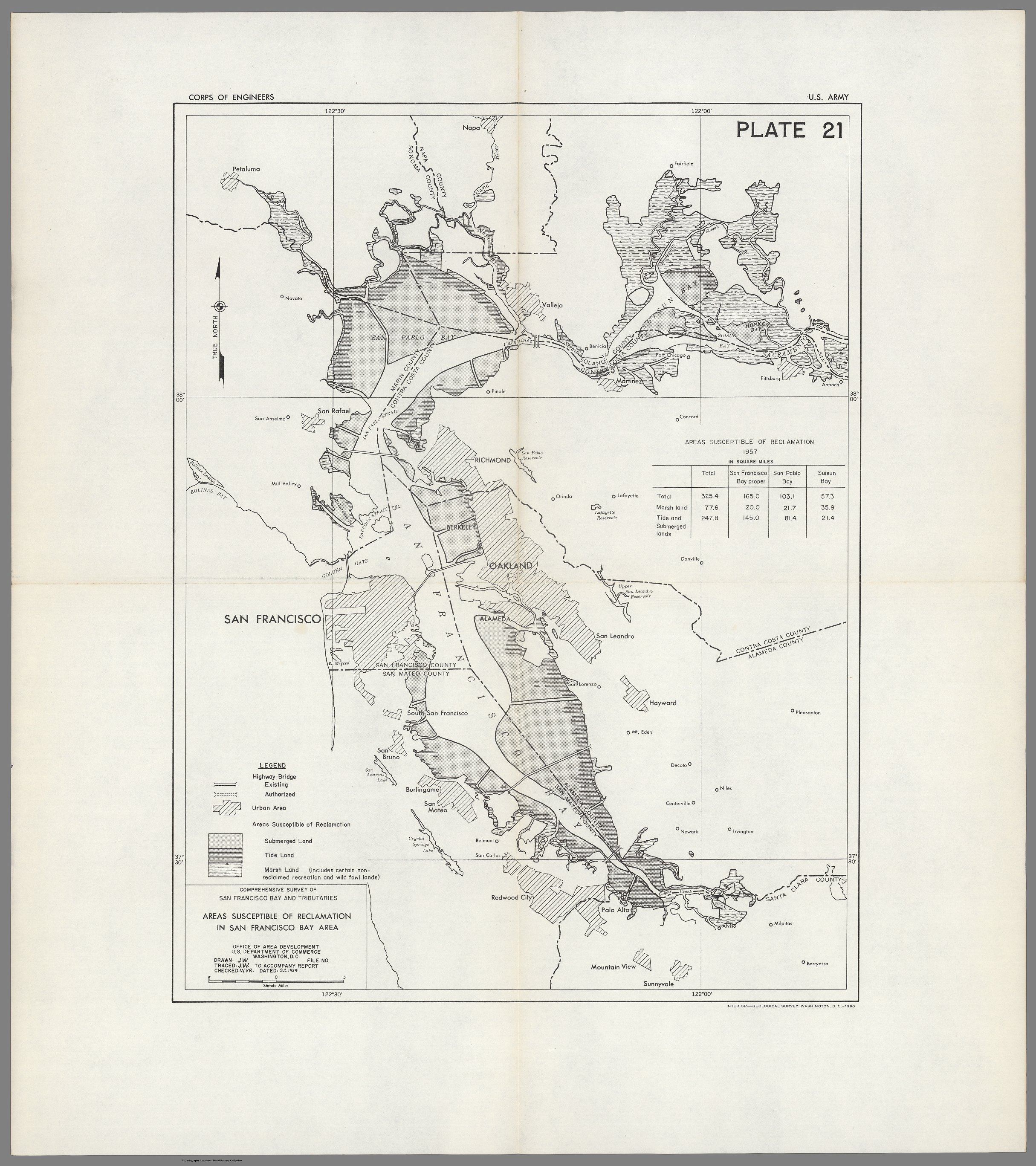

In the late 1950s, the Army Corps of Engineers did a study on the development of the Bay Area. They found 243 square miles of land “available for reclamation” had been reclaimed. That’s a lot of former marshlands, wetlands and tidal lands to have drained or filled.

You can read the full study here. It’s wild.

What are the problems with artificial fill?

By the 1960s, we mostly stopped filling in the Bay because of growing environmental concerns. After the Army Corps of Engineers did its study of the Bay Area, they published a map projecting what the bay would look like if we continued to fill it in. The picture so alarmed people that eventually the state Legislature put an end to bay fill.

The other major problem with artificial fill, which wasn’t well known 100 years ago, is the earthquake danger.

According to Keith Knudsen of the U.S. Geological Survey, the fill built on top of bay mud or soft ground is at risk for ground failure or liquefaction during an earthquake. A lot of that old fill was not built with the best engineering practices. It was also frequently placed on top of mud or soft deposits, which amplify shaking. When you have high ground water, loose materials and heavy shaking, those deposits can stop behaving like a solid, and start behaving like a liquid, said Knudsen.

The ground turns into a sort of quicksand. Buildings on top can sink and crack. Also things that are in the ground and filled with air, like sewage pipes, can float to the surface.

“Lots of bad things can happen if the ground liquefies,” Knudsen said.

What’s being done to mitigate those issues?

The best way to prevent liquefaction and ground failure is to take steps when you’re first creating the artificial fill.