During President Trump's first term, the transformation of federal immigration policy has been far-reaching and so broad that experts say the effects could last for years — even if he isn't reelected. Here are nine ways he has overhauled immigration in the U.S.:

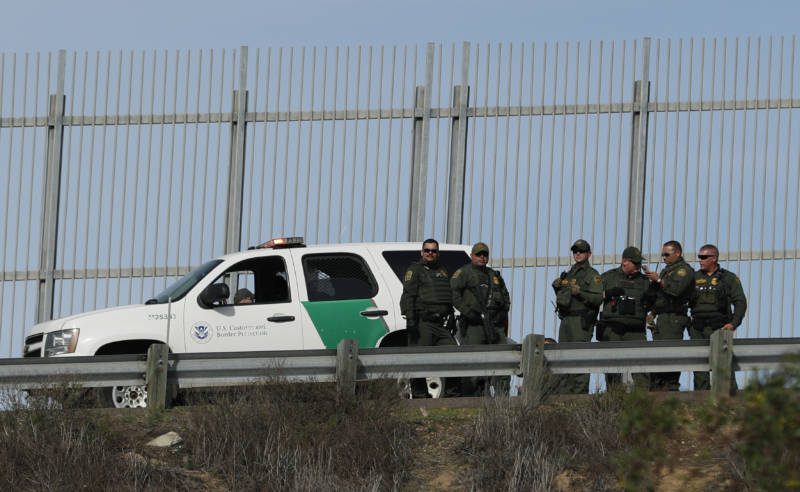

1. Trying to build a border wall

Trump’s pledge that he would build a wall on the Mexican border (and making Mexico pay for it) galvanized enthusiasm among his supporters, but it has proven difficult — and costly.

Congress approved much less money than Trump requested — $1.3 billion in the 2020 spending bill, rather than $8.6 billion. The president declared a state of emergency and channeled billions more from the Defense Department to Homeland Security. Advocates and a group of states led by California sued, and federal judges in California and Texas ruled that Trump was wrong to flout the will of Congress. But conservative court majorities have recently allowed construction to move ahead.

As of January, the government had built one mile of new barrier and 100 miles of replacement or secondary fencing — at a cost of almost $20 million per mile, NPR reported.

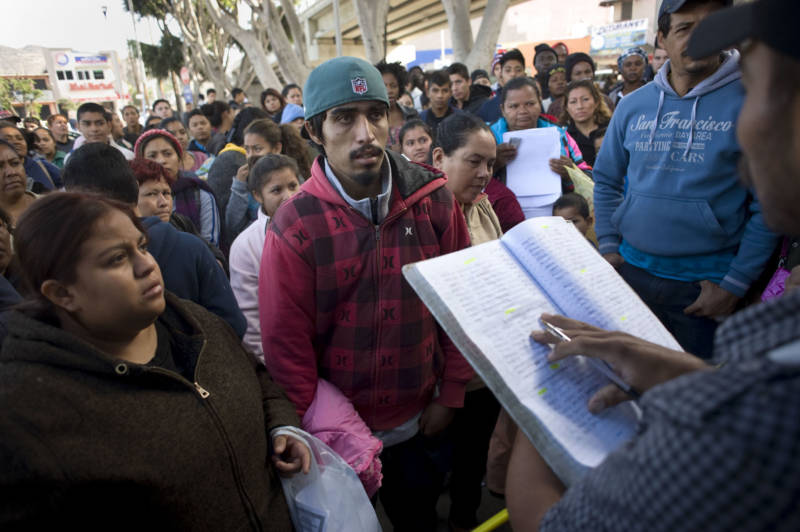

2. Restricting access to asylum

The administration may not have gotten far with a physical wall, but it has succeeded in erecting a virtual wall of regulations blocking tens of thousands of migrants from requesting asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The law says that people who reach the U.S., regardless of how they get here, can be granted asylum if they can prove a well-founded fear of persecution.

In November 2018, Trump issued a federal rule barring people from applying for asylum if they didn’t enter the country at an official port of entry. Federal courts have blocked the rule and the case is currently before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Another rule, issued last July, made people ineligible for asylum if they crossed a “third country” on the way to the U.S. but didn’t apply for protection there. The U.S. Supreme Court allowed that policy to take effect while a lower court in California hears a legal challenge. Few migrants from Central America and beyond have pursued asylum claims in Mexico, so they are virtually shut out at the southern border of the U.S.

In 2019, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador signed agreements to receive and consider asylum-seekers that the U.S. sends them. So far, the Trump administration has flown scores of Hondurans and Salvadorans to Guatemala — despite the fact that 200,000 Guatemalans fled insecurity in their country last year.

Over the past year, Homeland Security officials also sent about 60,000 non-Mexicans back to Mexico to wait while their asylum cases are decided in U.S. immigration courts. People in the so-called Remain in Mexico program have found it next to impossible to obtain U.S. immigration lawyers. Only 187 people in the program — or 0.3% — have won their cases, compared to 30% of all asylum seekers last year, according to researchers at Syracuse University. Currently an estimated 20,000 people are camped in Mexico’s most violent cities, awaiting their day in court.

3. Separating families and zero tolerance

Removing migrant children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border was one of the Trump administration’s most controversial steps. Americans reacted to the sight of sobbing children with a broad, bipartisan backlash in 2018 that led President Trump to reverse the policy.

The separations began quietly in 2017 and increased in April 2018, after then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a “zero tolerance” policy aimed at criminally prosecuting all adults — including parents — who crossed the border without authorization.

In 2018, a federal judge in San Diego ordered a halt to the separations and the reunification of families. More than 18 months later, perhaps as many as 2,000 of the more than 5,500 separated children still have not been reunited with their parents.